In this episode, Risa and Carol Gigliotti talk about animal creativity and animal cultures, listening to trees, feminism, and the source of all Earth inspiration.

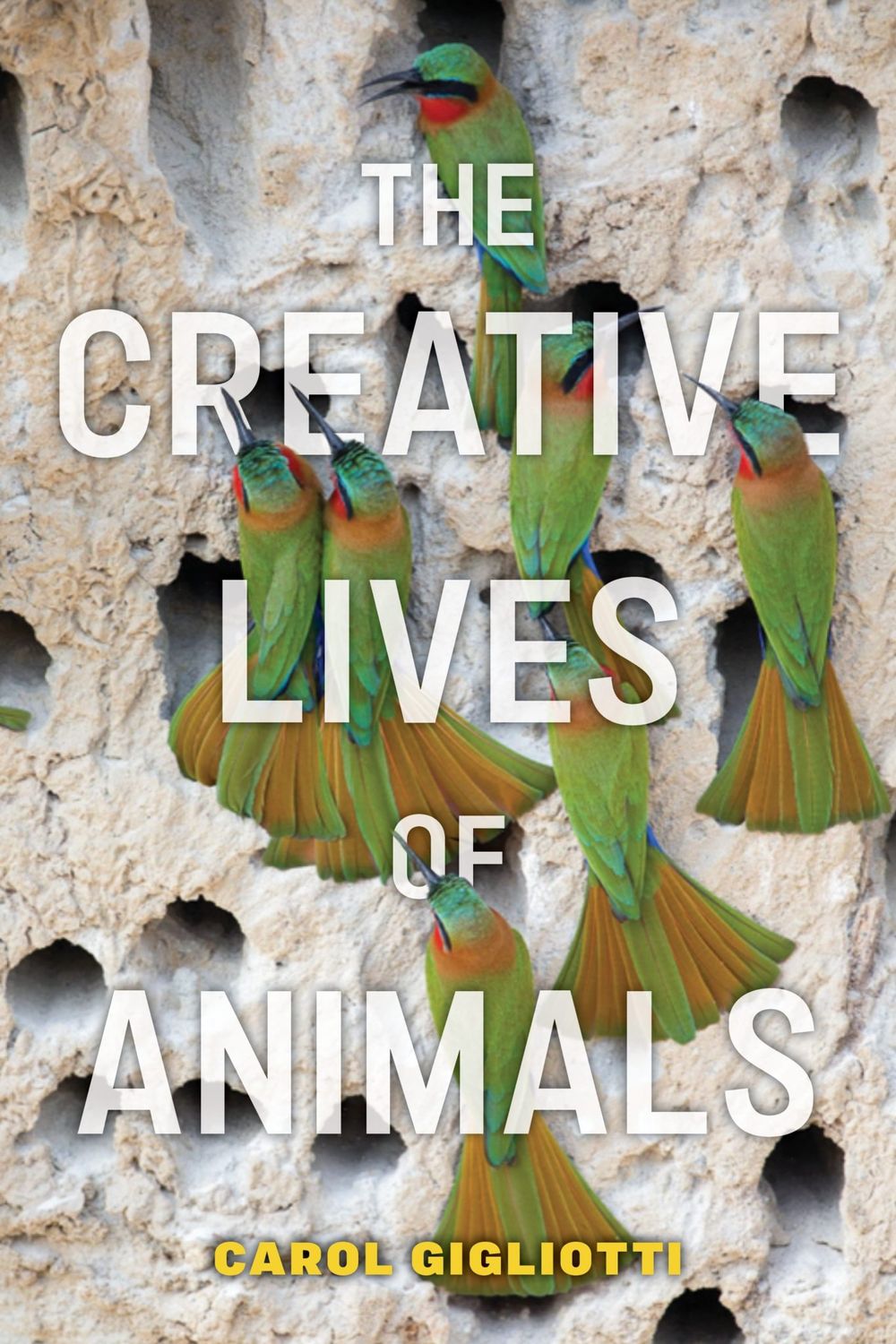

“Carol Gigliotti is an author, artist, animal activist, and scholar whose work focuses on the reality of animals’ lives as important contributors to the biodiversity of this planet. She is Professor Emerita of Design and Dynamic Media and Critical and Cultural Studies at the Emily Carr University of Design, Vancouver, BC. CANADA. Her new book, The Creative Lives of Animals, can be pre-ordered now. It will be published from NYU PRESS Nov. 22, 2022.

The Creative Lives of Animals offers readers intimate glimpses of creativity in the lives of animals, from elephants to alligators to ants. Drawing on a growing body of scientific research, Carol Gigliotti unpacks examples of creativity demonstrated by animals through the lens of the creative process, an important component of creative behavior, and offers new thinking on animal intelligence, emotion, and self-awareness.”

Full Transcript

Carol Gigliotti

Risa: [00:00:00] The Missing Witches Project is entirely listener supported, and listener will want you to join us. Do you wanna be part of a community that helps make public research into marginalized ideas? Do you wanna join in interviews with all these magical people and meet other anti-racist, trans-inclusive, neuro queerer feminist practitioners of different kinds from all over the world in our monthly circles Or are you maybe just down to send a little money magic towards these stories and ideas and the causes we support? Anyway. Either way, check out missingwitches.com to learn more about us, and please know we've been missing you.

Risa: And one last thing before we start. The stories we tell require a general content warning. It's just a fact of this terrain of interrogating what is missing. We promise to hold those moments with care.

Intro: You aren't being a proper woman. Therefore, [00:01:00] you must be a witch. Be a witch. Be A witch. Be a witch. Be a witch. Be a witch. Be a witch. Be a witch. Be a witch. A witch. You must be a witch.

Risa: Welcome Coven, welcome, whatever state your brain is in. My Loves. Mine is sort of a froth of joy and new ideas and exhaustion and terror and delight at all times. I don't know if that describes your brain chemistry, but that's sort of where I'm at. Welcome back to The Missing Witches Podcast, and I'm so excited to be here today with the author of the Creative Lives of Animals, Carol Gigliotti. We've been slowly discovering each other's work and going through kind of hard times together, actually quite lovingly, over email for the last couple months, and Carol's book is so, fucking rad, and so beautiful. It's so exciting to see so much research so eloquently [00:02:00] put together from the perspective of both art and science to make the case for not just the kind of generalized idea of creativity in animals, but in the individual and cultural creativity in animals.

Risa: That's, so I think core to understanding how a future saving kinship could work, right? There's so much power in all of this research, and so to get to talk to you is really rad. I'm so, excited that you're here. How are you?

Risa: Tell us everything.

Carol: Okay. I'm doing very well, doing much better than when we were emailing back and forth.

Carol: I'm happy that we were able to meet through my son, actually,

Risa: A beautiful writer in his own right.

Carol: Yeah! So, I have just been really focusing on the book, publicity and marketing. So, [00:03:00] yeah, that's been exciting and kind of overwhelming. I have a terrific publicity and marketing team at New York University Press.

Carol: They're amazing. You know, it's been a, it's actually been a long haul, it's been almost 10 years. If you look at everything. There are lots of downtimes. But yeah, I've kind of been working on that book for 10 years. That's quite gratifying to hear you talk about the book like that because boy, you got it.

Carol: That's exactly what the book is for.

Risa: Do you feel like in that 10 years it was hard to make the case? Like is it easier to make the case now about the creative lives of animals, about their importance, their minds?

Carol: I thought it would be difficult until I really started doing the research, and once I started doing the research. I was like, this stuff is all out there! Over the last couple years, you know, every time you open the paper or open a magazine or, well, I never do [00:04:00] that anymore. I always look online and so does everybody else. But there are tons of articles about animals doing, sometimes they call it creativity.

Carol: Sometimes they just say amazing. It's not really amazing. It's just we've been so blind all this time, myself included. I did not find it difficult at all. In fact, I had so much research I had to sort of, I can't keep writing a book forever. I'm gonna. I'm gonna have to sort of, you know, stop at some point, which of course I haven't really done yet.

Carol: I keep putting things away, you know, maybe for another book, but no, it wasn't hard. It's really important for us to open our eyes and it's really hard to do that. And there, are other people out there and other books, tons of books right now that are just so interesting and, even if they're not talking about it in terms completely of creativity, it's the way they're writing about it. The way they're sort of putting [00:05:00] it in a context is just so useful, I think, and, meaningful in terms of the kinds of things I'm writing about. I could not have written a book without all the scientists and I never thought I would say that.

Carol: I've always been a kind of critic of science. Also loved it. You know, it's like a love hate relationship. I certainly could not have written a book without all the research I did. I think it was really important to back it up and support it with people who were actually in the field. Some of them working with one animal, one species of animal for their whole lives, their whole career.

Risa: So why do you think that when there is so much work, why do you think we still have such a hard time really seeing them?

Carol: I think the major [00:06:00] reason that it continues, is that if we really thought of animals as other nations rather than underlings, which is sort of, a paraphrase of Henry Beston's quote about animals. Great book, the Outermost House. I think, most people would have to stop eating them, stop wearing them, stop using them as slaves. And if I could just answer the science.

Risa: Yeah, please.

Carol: What I've found, and this is really interesting to me, is not all the research, I used, was about creativity. I thought in terms of what I've taught for so long and how I thinked about creativity, I could see all these little threads that needed to be put together. And there are people, biologists, you know, studying creativity. I really tried to look at it from the creative process, which I thought would open up a lot of area and a lot of space [00:07:00] for the individual animal.

Carol: How we could, we as human beings, could see how that creative process exists in animals, just as it does in us. But in very many ways that really do not exist in us because, we don't emit scents that are ultraviolet. So, for instance. But the other thing I found, and this was interesting, is that a lot of the people I interviewed had been pathologists, evolutionary biologist, scientists for quite a while, and they're at the point in their career where they're like, nah, I see this. This is what it is. I'm not backing down, you know, which is something that Jane Goodall and, and Frans de Waal say that, you know, you just keep hammering away that, this is what it is.

Carol: And after a while, all the other explanations go away because they [00:08:00] just really don't make sense. And the one that stands up is the one that is, the simplest. If you think about evolution is that, we're created, evolutionary thought makes you think and of course Darwin thought this, that they're creative too.

Carol: I also found those people were, were older and then I found lots of younger scientists, biologists, all kinds of different, you know, ecological biologists. I mean, there's just lots of work going on in terms of ecology and, and biodiversity and younger people who were like, of course, of course.

Carol: And were not so, what burdened with behaviorism, but, and that, that I think is coming about slowly. I wish it wasn't so slow because we need it to be quick. We we're at the point [00:09:00] in our planetary health, that if we don't figure these things out, we're, as we all know, we're gonna be in deep trouble.

Risa: Yeah, that's the terror that lurks.

Risa: I mean, I love hearing that more and more scientists just see it as obvious, and especially, that it feels like a tide of just obviousness that you encountered. That's quite reassuring. But how, it leaps over those gaps from science. And it's in popular discourse too, right? Like as you point out, you know, every other thing on the internet is like a bear being brilliant and hilarious or whatever, a cat, and you're like, we all know it's intuitive.

Risa: We know they're individuals, they're playing, they're communicating.

Carol: Well, I think, in terms of writing a book, most of my other writing has been about our negative relationships with animals. And it has been in the area of critical animal studies and [00:10:00] what biotechnology is doing to animals and how we think about animals and how we use the animals.

Carol: But I really, to be honest, I really wanted to write something that would be popular that would get to not an academic audience. There's some stuff that's a little heady in there, but I try to break it down. When I was teaching Heidinger, and you throw Heidinger at students, then they're like, Ack!

Carol: And then you break it, you just break him down. You just, not poor Heidinger, but...

Risa: Break that guy down a little bit.

Carol: Break down his thoughts and really, it's not that they're not profound, but you know, they are profound in their simplicity in some ways. I mean, my goal is to really always get to understanding something and never being opaque.

Carol: I really don't want my writing or my [00:11:00] thought to be so opaque that nobody understands it. Because why bother? You know?

Risa: Yeah truly. It's still hard. I mean, when you're in an academic discourse all the time, to break out of that language and speak clearly is really hard. And, as a spell, I think if you can do it, you know, like it really is like, can you break out of that one language into a whole other language?

Carol: Well, when I retired, that was my goal, really was to retire and write the book. And so I'm old enough to be able to do that, but it still took 10 years. I still went with an academic press and, I will say there's lots of good stuff coming out from academic presses because they're much more open to ideas, especially at a press, like New York University Press that are open to new ideas that aren't particularly always accepted.

Risa: I want to think about your history in the arts, coming to this science conversation and being the one who can see [00:12:00] it. That artist's perspective, that can open up science sometimes. And how you feel you're understanding of teaching, kids teaching creativity. You talk about it in the book, how your understanding of creativity allowed you to write this book, to see these things.

Carol: Yeah, I certainly didn't come to this in my thirties or forties. I didn't really get into academia, higher ed, until my forties and I went back to get my doctorate. I already had MFA in printmaking, and then before that I had a BSS, which I always love that. Yeah, but what?

Carol: It's really a Bachelor of the Science of Speech. I'll be real honest with you. I had a very serious car accident and I couldn't move my head. I couldn't really do much of anything for a while, and I could read if I held the book up somehow, and I started reading. [00:13:00] Like everyone does when they're in a car accident.

Carol: Physics...

Risa: What just happened to me? Break it down from the fundamental particles.

Carol: Yeah, I had read Annie Dillard and her first book, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, and there was so much in that book. She really looked at older kinds of science and so I got a number of those books and they led me to read in conceptual physics and pretty soon everything kind of changed in terms of being really interested in science in a way that I had never been before.

Carol: And so, the idea that science is problematic and that sort of objective view. I mean, I knew that already, but this, I wanted to know more. The Leonardo's Choice book was [00:14:00] about how science and biotechnology specifically was affecting, not only animals themselves and changing, this is still going on, of course, changing genetic codes of animals so that they're much more what we want them to be.

Carol: And that whole idea of, that our creativity is about changing things in to make it more like us. Seems to me to be a real dead end when you're talking about creativity. You're cutting out any kind of flexibility or openness to the world around you. And if we, I say this in the book, if we end up with just us, we're sunk.

Carol: We are only one small part of the universe, and 1 species [00:15:00] among 8 million other species on the planet, and we really have to think of things like that, or we will never understand the way to be a good, planetary citizen, for instance. When I had gotten my PhD, I worked at the Advanced Computing Center for Art and Design and Computer Science.

Carol: So, I started to get this view of science that wasn't so negative. I was up in a cabin, with my son in the snow and I was taking a computer science course and this was before I went to Ohio State to do the PhD, and I was reading about If-Then-Else, a very basic kind of way to write algorithms.

Carol: I was totally shocked. I, for some reason, had never understood, and which was probably a real problem, that if this [00:16:00] happened, then this would happen. But if you did this, this might happen. So the idea that things were possible, If one thought about them enough.

Carol: I mean, certainly I understood that, but that I could change it? That all I had to do was keep going? But if this, that was a major, and I know this sounds, I've said it to computer scientists and they're like, really? But for me it was this major breakthrough.

Risa: Well, sure, I think an artist and thinker in the woods comes to it and goes everything is open. Like change is everything. Everything is change. I am in the moment of choosing change at every path, and this person who did this computing laid out a certain path for me. But those aren't all the paths. And I think that also helps us think about the built world, right? Versus the animal world or the living world that's around us.

Risa: [00:17:00] We're set up into this limited set of possibilities. If this, then this,

Carol: Yes.

Risa: But they're with us, too going like, no, also this.

Carol: Well, and you know, when I wrote my dissertation, I actually wrote it using Brecht the dramatist, and his idea that we are not, against Aristotle. It's not about destiny, it is about choosing what will happen, choosing to be good, choosing to look at animals in a different way, choosing to be vegan or whatever you're doing and choosing not to kill someone, even a human or an animal.

Carol: So, those kinds of things I think led up to the book. And some of the thinking behind it. And this kind of openness to biology particularly, which I also have been interested in. But it [00:18:00] was also meeting people like Mark Bekoff, who's a biologist, and his writings and his books are really wonderful because they just lay it out for you. And he's a biologist who's worked with, wolves and coyotes and all different kinds of animals. But his ideas on play I think are really powerful and certainly play is an enormous part of creativity. You know, you take kids who've never been played with and they have a hard time doing anything creative.

Carol: Or anything else for that matter. Certainly in the US there's a lot of problems with kids. You know, only doing what the teacher wants. "Is this what you want"? I don't want you to do what I want you to do. I want you to think about what you want to do, and then do that. See what happens.

Risa: Yeah, it makes me think about, if we're genetically modifying animals into being more, [00:19:00] not just like us, but what is useful and subservient to us?

Risa: And the kinds of creativity that we're losing, right?

Carol: Exactly, exactly, yeah.

Risa: I found I was so moved in the conclusion of your book, when you talk about, I'm gonna paraphrase it so badly. You talk about this idea of cultures that is so much of the focus on biodiversity. Preserving biodiversity focuses on, make sure we have X amount of X species, but we're missing the individuals, and the cultures within species.

Carol: Yes.

Risa: The leadership of mothers among elephants, so we didn't notice and lost a lot of moms and lost a lot of history and a lot wisdom ingenious in those families. Yeah. I was really, really struck by that making it so concrete, we have to look for the creativity in these animals. And not just to think about it in this broad general stroke of [00:20:00] like, ants have instinct towards this or there's, a uniqueness there that has to be looked at in such a fine grain way.

Carol: Yeah, and well, two things.

Carol: One needs that, and I'm blanking on his name, Moffitt, I think.

Risa: We'll put the link in the show notes.

Carol: Okay. And he talks about being able to tell individual ants who's what because he's studied them for so long. He's down on the ground looking at what they're doing. And certainly you know Tom Sealey, I'm sure you read the bee section about Bee Democracy.

Carol: He has a book out on Bee Democracy that everyone should read. And I talked about his research. That was really wonderful, that individuals are so important. In deciding where the next nest is gonna be, but how the individual then gets together with the group and then it's decided. [00:21:00] Which nest, which area is best.

Carol: He calls a quorum, they decide in a quorum. So it's not everybody waits around for everybody to agree, which is sort of what we do in meetings, which is like fruitless. But it is, we need a nest, we need this particular, and the requirements for a bees nest are very, very particular and very precise.

Carol: And so they decide which one is the best with most of the bees, most of the scouts that are doing this actually agreeing and there's much more to that. Read Bee Democracy because it's really quite useful for what's going on in our country right now.

Carol: Boy, I wish people would read that.

Risa: Wild, well, that's top of my list now.

Risa: Can you give us some other examples of kinds of creativity that you were delighted by, doing the research?

Carol: One of the things that I thought was really, and I really didn't know very much about was [00:22:00] desert iguanas emitting scents that reflect ultraviolet light. I mentioned that before, to mark their territories and then the other iguanas see the ultraviolet light in the markings and they stay out of the territory.

Carol: Now, we could never do that. First of all, we can't see ultraviolet light without help. So there's that, and this idea of, different kinds of communication. Elephants using infrasonic rumblings, which they kind of knew about before, but how did they do that? They hear those rumblings through their enormous feet.

Carol: And they can hear these from miles and miles. So they're communicating and telling each other, you know, where another elephant group is, and what's safe, what isn't, whatever it is they're talking about.

Carol: And this one [00:23:00] I actually got from Richard Prum. Richard Prum is really interesting and brilliant guy who wants us to think very seriously about sexual selection in evolution. Not just natural selection and how animals select for, desires really. For instance, the Bird of Paradise, I don't know if you know the Bird of Paradise, but they're really beautiful, gorgeous birds. Well, the males are, because the females are the ones that judge, they sing and dance.

Carol: I mean, Cornell University has a whole project that was done by a photojournalist who's a biologist and a biologist who went to where Birds of Paradise are, and documented them for a number of years and then went back. They realized really what they were seeing was not [00:24:00] what the females were seeing.

Carol: Once they put the camera to see what the female was seeing. Good Lord. Completely different. And so that idea, and I went off to Prum from these other two scientists, is that females have had a great deal of power in actually being able to decide what is beautiful to them. And in terms of the kinds of biodiversity that we think about in terms of, the beauty of the world, certainly females have had a lot to do with that in a number of situations.

Carol: Not always just about beauty, but I think that is one of the most, at least for me, was sort of mind-blowing kind of thing. And once I got onto that project, I literally, I got addicted and I'm sure that slowed the book down. And really, once you get to this you won't be able to get off, so [00:25:00] just be prepared.

Risa: I'm here, I'm ready for it.

Risa: I wanna ask how this work intersects then with your feminism. Not to derail you, because you're, you're in the middle of a thought, but I wanna know that too.

Carol: Well, I know certainly Prum actually mentions that and I love him for it. He talks about the fact that, feminism is not just some sort of idea, human idea, but it's actually biologically very important.

Carol: And, he goes on to talk about all kinds of ways, ducks, for instance, which I hope I don't screw up telling this. There's a long section about ducks. The idea that, male ducks are quite aggressive, and so the females have developed vaginas that are really complex and sort of allow the duck to put off the male because, they're kind of like corkscrews. And then, the male has [00:26:00] also figured out biologically well then, okay, well we're gonna do this. I don't know if you call duck's, penises, but it's been reshaped as well. And so this could go on indefinitely, which, kind of sounds like, men and women in general, you know?

Carol: But yeah, there's just so many things like that. And also, I think we were talking about, the idea of feminism a bit in another context. There's so many animal studies, or women who have been writing about animals, who certainly are feminists as well. I mean, certainly you can't, talk about that particular subject without talking about Carol J. Adams, who wrote The Sexual Politics of Meat, and she's very active and has a number of other books out. A friend of mine, and just a wonderful person, and then there's a sort of a different care [00:27:00] perspective for animals that goes along with feminist thinking, Josephine Donovan.

Carol: I think feminist thinking has really influenced the kind of thinking that we have on animals. I mean, if you go back through history, there's been lots of women who have started "animal welfare". I'm using quote air quotes, who really cared about animals. And I think one of the reasons is women and people who are discriminated against for race or sex, well, sexual proclivity, anything like that for their cultures.

Carol: You know, have that understanding of what it's like to be seen as inferior and second class. And I think that allowed a lot of women to really understand animals in a way. I'm not saying that there aren't wonderful, men who are involved in animal rights and didn't come to it from that. But [00:28:00] I think that's really true in terms of feminism itself as a movement.

Carol: If you go back, an early feminists really in Britain was Bridget Brophy, who was a feminist and an activist, and she died very young, unfortunately in 1995. But she was very influential and was a fiction writer as well, and has tons of fiction books and non-fiction.

Carol: Val Plumwood in Australia, is known as an ecofeminist and has thoughts about animals I don't always agree with, but her understanding and her need to understand how animals exist in the world and in the habitats that they are in and what makes them so important for biodiversity. I think she's really good with that. Jane Goodall, of course, even though I think she says, you know, I don't know if I would call myself a feminist, but I was always the only woman in the room. And you know, Jane Goodall says she's been vindicated by how we are looking at animals [00:29:00] as individuals.

Carol: You keep mentioning culture, and I just wanna get to that because of all the things in the book. It's the last chapter, and I think it's really important because even biologists like Kevin Leland, who was very, very influential and really was one of the first people to talk about animal innovation and creativity.

Carol: They don't really go past that. Like humans do because we have culture and they're like, what? Animals do have culture, and I think as you said at the very beginning, that's so important to recognize. You know, a particular individual in a particular culture, group culture, it's not just one. You know, one species has a large culture.

Carol: They're all these different kinds of cultures, you know, and whales, the East coast and the West Coast whales are, have very different cultures in terms of what songs they [00:30:00] sing. So I think that idea of animal culture is really profound and I think it's really important for people to think about and I hope that books will come out of that. As well as what that means for conservation.

Carol: And I want to also note that I did include domestic animals like pigs and, well, I don't know if pigeons are domestic, but animals that we see as underlings. I don't want to compare animals and say, this animal's smart as this animal, because as far as I'm concerned, as when I was teaching, everyone is creative in a different way. We, all species are intelligent and creative in their way, and that doesn't mean that ours is superior. Ours is just one of those processes, one of those ways that we live in the world.

Risa: So can you then think out loud about this idea [00:31:00] that appears in your book about a new way of thinking about creativity?

Risa: What it is at all and where it comes from this, you know, this Earth, creativity.

Carol: One of the things that really helped me work that out. Was David Long, the physicist. All that reading I did when I was miserable and couldn't do anything else, I guess was important, was useful. Now I see that. He said, because in his book on creativity, quote, "it cannot be too strongly emphasized that what is being suggested here is that intelligence does not thus arise primarily out of thought, rather, as pointed out earlier, the deep source of intelligence is the unknown and indefinable totality from which all perception originates".

Carol: And, I give a definition of creativity in the book that really I [00:32:00] felt would work for biologists and also for the general public, the idea that individuals create "novel". That seems to be what biologists want, and I made a point of saying it could be novel for only that individual and that counts and meaningful and that what's not a word that a lot of biologists use, but I wanted to use, it's meaningful. It created something meaningful, not maybe to humans but to themselves, but also that would happen at an individual group species.

Carol: An evolutionary level. So I guess my thought about creativity being, instead of saying the deep source of intelligence, I kind of, when I read that, I thought the deep source of creativity is the unknown indefinable totality from which all biodiversity [00:33:00] originates. And that would include animals and I know that some people will think that means intelligent design.

Carol: I didn't mean that. And I know some people think that means there's a designer or, you know, this is very sort of Christian mysticism. It doesn't mean that. Evolution is what this planet is about. Now, whether or not in the cosmos there are other ways of doing things, I'm sure there are, but living on this planet, I think that is what I tried to get across and I think it's important for us to be, again, good citizens of the of the planet.

Carol: A planetary citizen, good planetary citizen.

Risa: You remind me so much of Octavia Butler in Earth Seed, right? You know, "God has changed. God is only change, but we dance with change".

Carol: And that's the whole lesson to learn. I don't like change. I love change everywhere. But you know, for me, [00:34:00] change is hard.

Carol: Everything's changing. So we are at a loss and, and I think it's a very uncomfortable moment for most people right now. Uncomfortable is probably an understated word.

Risa: I do think your book offers some kindness for that. While we're sort of in the overwhelm of how fast and how scary change is, I take comfort in this idea that there are communities and cultures around me that I can notice. That like an interaction with the other isn't so far away.

Risa: I have bees and ants and there's a mink that lives there. You know, I can bring my attention much, much closer and, that could still be of value because those are individuals. I can think about an interaction with those creative individuals and maybe that helps anchor me when I feel the loss of diversity happening, you know?

Carol: Yeah. [00:35:00] Thank you. I'm glad that's happened for you. Right? Despair is, I would like to sink into it, but it's probably not a very good idea. I think it's better to just keep working and fighting and, and making sure that voices are heard.

Risa: Yeah, just keeping sustained with what the truth is.

Risa: I'm gonna take both of those away from this conversation. Is there anything else that you think our listeners, strange, diverse, and glorious as they are? Many a witch, many of witch among them, and thank you by the way. For being willing to come on a witch podcast. I know for some scientists and academics that can be, and especially women working in scientific fields, who have been kept on the outside and treated like witches or emotional head cases, for some of the ideas that we have to bring into different fields, it can be asking a lot to come onto a podcast with this name and I take it really seriously. So thank you.

Carol: [00:36:00] I was happy to do it. I have friends who are Wiccans and I'm an artist, so, you know, really, nothing is strange to me anymore. But also I just had a grandson, as you know.

Risa: Yeah.

Carol: And called her, my son. He wanted to call me Nani after my mother. We used to call her Nani, but the, Italian term is Nonna, and so I wanna be called Nonna and we agreed. And then I realized there, there's a whole history, actually, I have a book on, on my bookshelf about Italian witches and there's also a children's book called Strega Nona.

Risa: Yeah.

Carol: So I've been going around saying I'm Strega Nona, grandmother witch. I don't have those thoughts about witches, I really don't. So, and if somebody doesn't like that. That's too bad.

Carol: Yeah,

Risa: I mean, [00:37:00] I think that art is a crucial tool of witchcraft if you want to follow it that way. To use it to transmit your life and see who you are and meet your shadow. So I think most artists are witchy whether they like the term or not.

Risa: I don't have to put the term on anybody who doesn't want it, but..

Carol: Yeah, I, I've felt a lot of terms put on me. So, kinder terms.

Risa: Well, we certainly mean it lovingly. I was starting that question before I went on that detour. Sometimes at the end of episodes, I like to ask, is there something that our readers can take from you? Like something you offer to them as a way to move forward in being inspired by your work. So sometimes that could be a ritual practice you have. Sometimes it could be, you know, a way of interacting or looking at the world or an art practice or something you want them to read.

Carol: You know, you asked me [00:38:00] about creativity, forms of creativity, and I think I have it here.

Carol: Oh yeah. It was a line from the book "for those moments when the clarity of the world was sufficient, and thinking about it became unnecessary". And I know you like that quote. And I have to say, I like that quote too.

Risa: I really, I really do. Not to derail, but I love that so much. And what a easeful way of thinking about anything we do to find that, those moments.

Carol: It's that anything we do, and I wanted to point out that, and for children. I know that happens. It happened to me. I'm sure it's happened to you where you were young and understanding the world just came at you like a comet and hit you on the head, you know, because all of a sudden you've just felt connected and part of the world, at least that's what happened to me when I was about five.

Carol: But there's other things like play. Play is created, and there's the whole idea of flow that you get [00:39:00] into a space where you don't have to think. I think play does that. I think caring for a human or an animal, and for me, one of the things is being with trees. If I go sit in the midst of trees and just watch, not only does it calm me down, but I feel as if I'm talking to another being or they're talking to me. Let's put it that way. I'm not saying anything. They're talking to me and there's more on that about drawing, but I'll end there.

Risa: I wish you wouldn't, but thank you. I feel very much the same about just watching trees and the way that that kind of, unparalizes my ego brain a little bit.

Risa: Thank you so, so much for being here. I can't wait to share the links to your book and to your work, and I already look forward to getting to speak again.

Carol: Thank you so much. I [00:40:00] really enjoyed this. I really have. You're great, keep going. I think that title is perfect. It's perfect and I think it really says what I think you're trying to do with the podcast very much, and I'm very happy to be here. Thank you.

Risa: Thank you, blessed fucking be. Don't hang up. That's just how we end the podcast.

Outro: Be a witch, be a witch, you must be a witch.

Risa: The Missing Witches podcast is created by Risa Dickens and Amy Torok with insight and support from the Coven. At patreon.com/missingwitches, Amy and Risa are the co-authors of Missing Witches, Reclaiming True Histories of Feminist Magic, which is available now wherever you get your books or audiobooks and of New Moon [00:41:00] Magic 13 Anti-capitalist Tools for Resistance and Re-enchantment coming fall 2023.

Episode Notes

https://www.doctorbugs.com/writing/the-books/adventures-among-ants/

http://pages.nbb.cornell.edu/seeley.shtml

https://www.cornell.edu/video/thomas-d-seeley-lives-of-bees

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/8705048-honeybee-democracy

https://caroljadams.com/spom-the-book

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/491750

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2008/mar/26/australia.world