This essays follows from the author, Cristian Horgos's, previous writing on the astronomical imagery in the channelled paintings of Hilma af Kilnt.

Across the long arc of human imagination, a single shape recurs like a memory older than language: the spiral. Carved into megaliths, painted onto pottery, incised along the bodies of Neolithic figures, spirals appear wherever our ancestors reached for something more than survival.

One of the most compelling archaeological archives of this symbol comes from the Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, which flourished across parts of present-day Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine between roughly 5500–2750 BCE. This was a society known for its vast, planned settlements, its remarkable ceramics, and its abundance of female figurines—objects whose meaning remains debated but which clearly held profound ritual importance. Some scholars argue that Cucuteni–Trypillia communities may have been matrifocal or matrilineal; others urge caution. But the sheer density of goddess-like forms suggests a worldview shaped, at least in part, through women’s bodies, women’s labour, and women’s cosmologies.

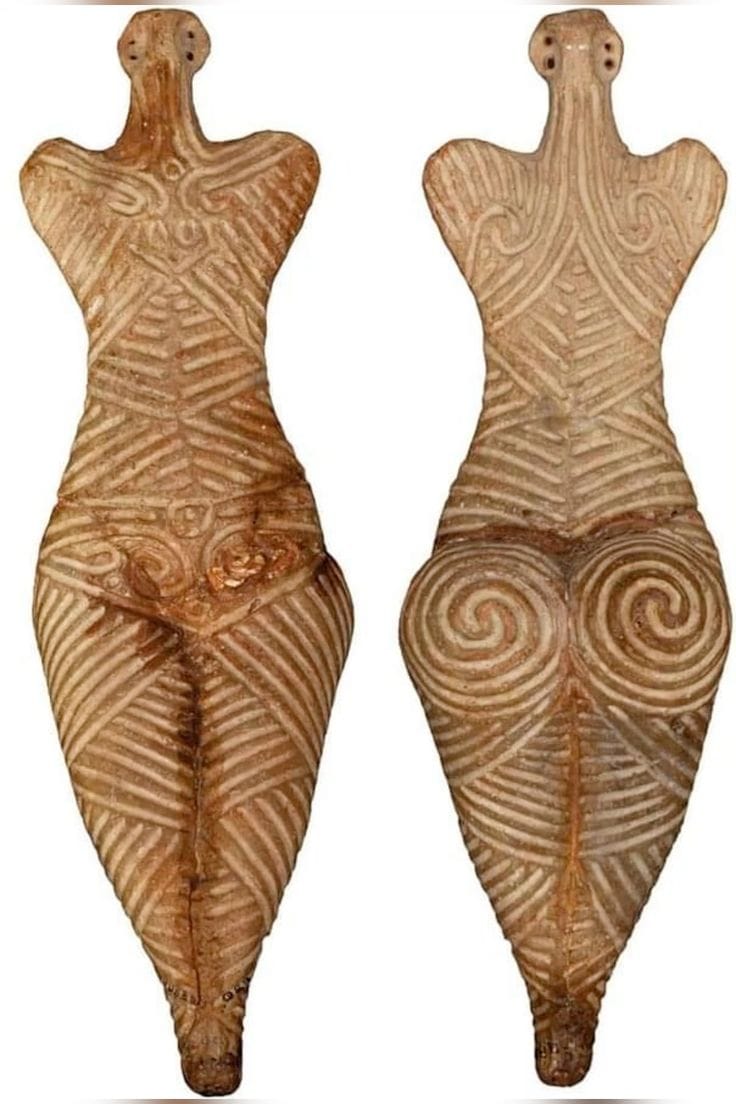

In contemporary magical circles, these enigmatic figurines are sometimes affectionately called the “Cucuteni witches.” The term is tongue-in-cheek, not historical. These Neolithic communities did not leave behind spellbooks or explicit evidence of magical practice. But calling them witches gestures toward something we can see plainly: figures that held power, mediated household and cosmic forces, and bore symbolic systems that still speak to those who work with trance, ritual, and altered states today. The spirals carried on their bodies—visible on pieces like the Venus of Drăgușeni—invite us to read them not only as deities of fertility or earth-power, but perhaps as early diagrams of consciousness, continuity, and the possibility of survival beyond death.

This essay follows those spirals—across Old European ceramics, global megaliths, altered states, and evolutionary theories of how mind shapes and reshapes itself—to consider a provocative idea: that a form of afterlife might have emerged not in spite of evolution, but through it. If the first living cell arose from the improbable chemistry of ancient Earth, why not imagine that human imagination, ritual, and longing—practised over thousands of years—could help sculpt a surviving layer of consciousness? A psychic echo. A collective imprint. A kind of immortality co-created by brains under existential pressure.

From Cucuteni spirals to thinkers like Tesla, Huxley, Sheldrake, and Jung, we explore how the human mind may have shaped not only its myths, but the subtle conditions for its survival.

From Cucuteni spirals to the idea of immortality

The Neolithic Cucuteni culture is especially known for its spirals. They appear on pottery, on ritual vessels, and most strikingly on the bodies of figurines—such as the so-called Venus of Drăgușeni. While the “Mother Goddess” of the Neolithic is often interpreted as a symbol of fertility, nature, or the generative earth, the Cucuteni goddesses—or “witches,” in our contemporary shorthand—might also point toward an early intuition of immortality encoded in their spirals.

Spirals appear across many Neolithic sites: Tarxien in Malta, Castelluccio in Sicily, Newgrange in Ireland, Piódão and Chão d’Egua in Portugal, Pierowall in Scotland, Bardal in Norway, Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, La Zarza–La Zarcita in the Canary Islands, and countless others. It is difficult to imagine people moving and carving massive stones for decorative whim alone; the ubiquity and labour required suggest the spiral held deep connection to consciousness and cosmology.

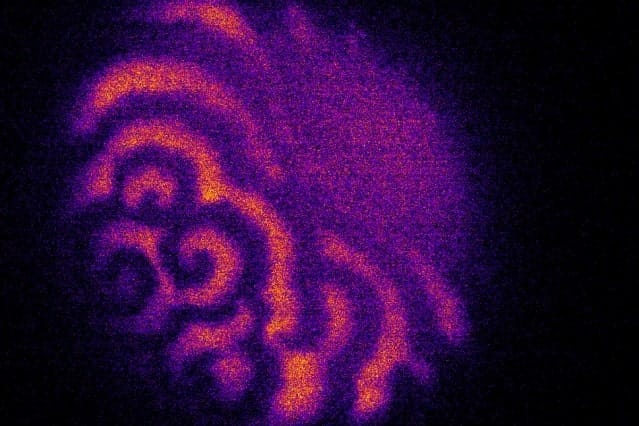

Researchers David Lewis-Williams and David Pearce, in Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods, offer a provocative interpretation: spirals correspond to specific stages of altered consciousness that lead to visionary experience. Other authors have read spirals as symbols of the soul’s passage into immortality. Looking across the world’s ancient megaliths, it is easy to sense that carved spirals may have been early attempts to depict eternity.

Even in modern accounts of regressive hypnosis, when individuals report contact with what they describe as the essence of consciousness or soul, perceptions of spiralling vortices are common. The symbol persists.

Afterlife on Darwinian terms

The first miracle is the appearance of life itself: the emergence of a single living cell from an extraordinarily precise alignment of organic conditions. If such an event occurred once, why could another miracle of consciousness not arise?

To imagine an afterlife through the lens of evolutionary law may feel like belief rather than science—but the Neolithic record offers hints worth considering. Even if the odds are one in a thousand billion, what foundation allows us to claim with certainty that a form of consciousness-survival based on evolutionary processes has not appeared, or could not yet appear?

This essay explores that tiny but potent possibility—a speculative foothold for those searching for purpose.

Modern thinkers have contemplated something like this. Nikola Tesla described the brain as a receiver tuned to a universal nucleus of knowledge and inspiration. Aldous Huxley, in The Gates of Perception and Heaven and Hell, argued for a collective dimension of consciousness and imagined individual souls surviving in a vast congregation of all souls. Rupert Sheldrake developed the idea of morphic fields. Carl Gustav Jung rooted analytical psychology in the idea of a collective unconscious.

If an imprint of the individual psyche survives within a timeless collective field, that imprint becomes a form of immortality.

The question, then: how could such a “beyond” arise through evolution?

One possible answer lies in ritual repetition and neurological requirement. Ancient humans imagined heaven, desired it intensely, performed rituals for thousands of years, and believed in its reality. Perhaps the brain—remarkably adaptive—generated the “psychic substrate” necessary for a surviving consciousness in the same way earlier brains evolved new organs: eyes, ears, noses.

Jung’s synchronicity and “significant” adaptations

In Man and His Symbols, Dr. Marie-Louise von Franz summarizes physicist Wolfgang Pauli’s challenge to traditional evolutionary timelines. She notes:

Recent discoveries suggest that the selection of mutations by pure chance would have required far more time than Earth’s history allows. Jung’s concept of “synchronicity” may illuminate how rare, significant adaptations and mutations occurred more quickly than random mutation would permit. Such anomalous events seem to arise when there is a vital need. This could explain how a species under extreme pressure might produce significant—though acausal—changes in structure.

If necessity can precipitate non-random shifts in biological form, perhaps psychological necessity—the longing for continuity, connection, and meaning—could precipitate non-random changes in consciousness.

These would be the neurological conditions for the emergence of an afterlife: a spiral survival of energetic psyche shaped by millennia of desire, ritual, perception, and collective imagination.

An afterlife not as supernatural exception, but as evolutionary innovation.

Perhaps the oldest spiral carved into stone was not a promise from the gods, but a blueprint for what human consciousness would one day dare to become: an afterlife we co-evolved, carved from longing, pressure, and the ancient, ongoing will to survive ourselves.

Works Cited & Further Reading

Archaeology & Neolithic Consciousness

- Lewis-Williams, David, and David Pearce. Inside the Neolithic Mind: Consciousness, Cosmos and the Realm of the Gods. Thames & Hudson, 2005.

- Mantu, Cornelia-Magda. “The Cucuteni–Trypillia Culture: Between the Sacred and the Profane.” Documenta Praehistorica, vol. 37, 2010.

- Gimbutas, Marija. The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe. HarperCollins, 1991.

- Chapman, John. Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe. Routledge, 2000.

- O’Sullivan, Muiris. Duma na nGiall – Knowth and the Passage Tombs of Ireland. Stationery Office, 1996. (For Newgrange and related spiral iconography.)

Altered States, Symbols, and the Spiral

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. “The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art.” Current Anthropology, vol. 29, no. 2, 1988, pp. 201–245.

- Pearson, Mike Parker. The Archaeology of Death and Burial. Texas A&M University Press, 1999.

Evolution, Consciousness, and the Afterlife

- Jung, Carl Gustav, et al. Man and His Symbols. Doubleday, 1964.

- See especially Marie-Louise von Franz’s chapter “Science and the Unconscious.”

- Pauli, Wolfgang, and C. G. Jung. Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932–1958. Princeton University Press, 2001.

- Huxley, Aldous. The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. Harper & Row, 1954.

- Sheldrake, Rupert. A New Science of Life: The Hypothesis of Formative Causation. J.P. Tarcher, 1981.

Modern Reflections on Mind & Universal Consciousness

- Tesla, Nikola. “The Problem of Increasing Human Energy.” The Century Magazine, June 1900. (Primary source for the “my brain is a receiver” line, widely reprinted.)

- Harpur, Patrick. The Philosophers’ Secret Fire: A History of the Imagination. Blue Angel Publishing, 2009.

- Tarnas, Richard. Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. Viking, 2006.

Author Cristian Horgos is a mathematician and technologist living and working in Romania.