Today on the podcast we get to dig deeper into the life and work of Monica Sjöö thanks to her daughter-in-love Annie Johnston. Annie is a Women’s Rights activist who has dedicated years of her life to cataloging and preserving the vast amount of letters, photojournals, and artwork in Monica’s archive. She shares stories from her own memories and from the materials she’s inherited from this incredible writer, artist, and queer feminist activist.

You can listen to our first episode on Monica Sjöö here, for more storytelling about the artist and her impact.

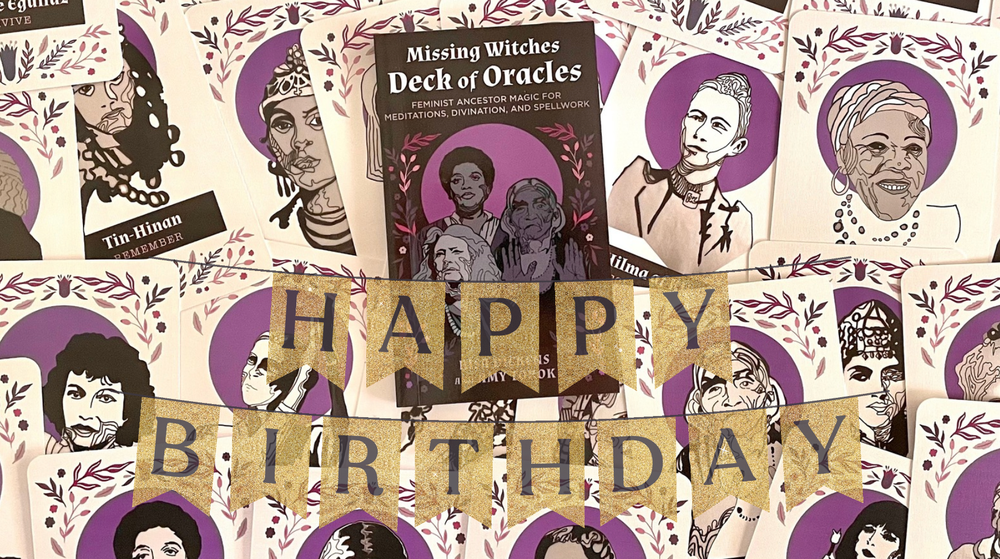

And read more about our emotional encounters with her thinking in our book, Missing Witches: Recovering True Histories of Feminist Magic.

Full Transcript.

[00:00:00] Risa: Welcome witches. Welcome back home to the missing witches podcast. Welcome listeners. Welcome friends. Welcome great extended and strange and powerful Coven in this joyful flourishing morning world. It’s been a while for me. I’m out of my rhythm a little bit. My mother-in-law is sick. And so, we are traveling back and forth, trying to figure out how we can be of support and give them space.

All my rhythms are off with this encounter, with the great. Rhythm maker, rhythm taker. But I’m here and I’m like cosmically thrilled. If you’ve listened to this podcast before, Monica’s Sjoo the artist and writer an activist was one of the first, stories people we encountered when we went looking for witches or practitioners or people who expanded our idea of what it meant to be a witch.

We were looking for activists. We were looking for people who weren’t just consuming other people’s cultures and repackaging it and selling it. And then we found Monica’s work and we’re totally bowled over by her. I keep a copy of her book great cosmic mother next to me all the time when I’m writing and dig through the index.

And then recently, stumbled upon Monica’s Sjoos, archive, have an estate, on Instagram and reached out and was like, is this really the estate . Is it real. And, the people who manage that were so kind, and it turns out it’s all family and all her grandchildren. And, I get to speak now with Annie, her mother in love, as she says and we have this in common, this sense of a great love with our mothers in-law and she’s here and we’ll just share stories about Monica’s show Annie welcome. How are you?

[00:01:57] Annie: I’m fine. Thank you. It’s good to be here.

[00:02:00] Risa: Can you start by telling us. A little bit about where you are, who you are, what your relationship was like. Just like, let’s get to meet you a little bit before we skip ahead.

Well, I actually met Monica when I was. 13 years old. Um, I went to one of her exhibitions and there was a show that she participated in. It was called the sister’s show with, with a number of her friends at the local art college. And I went and saw that. And then shortly after I became very into sort of the women’s movement and started going to the women’s meetings and the women’s center and met Monica there.

And I used to do a shift sort of volunteer shift down there. And, Monica would come in in this huge sort of big presence, you know, and she’d be sort of on one of her campaigns or whatever. She was a big personality. So I was a little bit like, Ooh, you know, who is this one? And got to know her a bit over those years.

And then eventually quite by chance and, and completely separately, I met her middle son. The son who survived because she had two that died. Not that long after his brother had died and I met him and then we became partners and we went on to have a family together and stayed together for sort of 20 years.

He sadly died two years ago. So Monica’s entire family now, has gone. They all left early. But, I got to know her, obviously initially as somebody in the women’s movement, who was a big powerful force. And then secondly, as a mother in love, on a very personal level. And actually during those years, when she was part of our family, she used to come and visit.

She’d stay for a few weeks and we’d stay with her and things. I just knew her as my, well, like my partner’s mom, you know, we went to some of her exhibitions, but I wasn’t particularly involved in the work or her books or, or even yeah. Like her politics and things.

So for me, it was a big shift after she died in 2005, all the archives, all the work came to us, which we were at that time living in Portugal. So I bought a van and, and, shipped it all out to Portugal. And then we, then I started going through all the boxes. Tovo her son, my partner was, was never particularly, he wasn’t really at ease with computers and systems like that.

So he was happy for me to do it and, and I enjoyed doing it. So that was fine. So then I started to sort of look at her work. More in more in detail and, and to get a, a sense of more of who she was as that person, that artist, writer, activist and everything. And that really has continued until now, because she left this massive, massive archive of, of work.

She documented absolutely everything that she did, or she partook in. She kept these huge photo journals also with information with flyers, with catalogs, with leaflets, everything that she was involved in, and it, it felt, and I think she knew from a very early age that she was going to be someone of importance and that was why she kept it.

So it’s not only a documentation of her life, but it’s also a kind of social record of the. Yeah, the culture and the social times, you know, going from the late sixties through to when she died. So there’s this mass of of the alternative movement, you know, alternative healing, alternative everything really that she was involved in and particularly the activism.

So that’s something I’ve kind of caught up on a bit since she’d died and been able to appreciate more of that side of her. And I’ve been carefully documenting every single piece of paper and trying to digitize it to, to go into this archive. She was a complex character and she wasn’t just an artist, she was a writer, she was a poet, she was an activist.

She was an ecofeminist, there’s just so many threads to keep hold of and, and to try and track. So that’s where I’m at now. still doing the work.

[00:05:53] Risa: Wild. I mean, I had a little bit of that experience. Of like, how do I pull all these threads from this person’s body of work and all the different people she corresponded with and all the different kinds of impact she had.

And I can’t even imagine receiving this like van full of an archive, how exciting and overwhelming. It must have been. Can you give us some, some like memories from the archive, some glimpses of things where you were like, well, this is unexpected or this is beautiful or this is cool.

[00:06:25] Annie: I think there was a, there was a lot of, um, early work that I’d never seen.

She actually went to do some life drawing classes in the 19 late 1950s. And I’ve never seen those before. And some, there was some abstract work, which I’d never seen either because quite early on, she decided to paint figuratively because she wanted to paint about real women’s life experience.

And she didn’t see how dots and squiggles could, could say anything. So that was a decision she made. So, there were, there was this, very early work, which like I say, with the life drawings, there were more abstract things which were experimentation. So that was quite a surprise really. And there was a period where she was obviously exploring sexuality as well.

So there are lots of drawings and small paintings around that, which I don’t think have ever, well, maybe they were exhibited in very early sixties, but not since. And most of those have been now been lost. I’ve got photographs of them because she documented everything meticulously, but no, Very little original work.

So that was one sort of area that I hadn’t expected to see. Um, and then I think in a way, yeah, the, the photo albums were also, I didn’t realize the extent of them. There was just hundreds of these massively fixed or volumes that were full crammed full with photographs and notes. And yeah, like I said, flyers and catalogs and, and letters from people and things like that.

So it’s the extent I think. One thing I didn’t mention before she was an absolute, incredible networker, and this was way before computers existed. You know, she, she wrote letters and postcards and sent them all over the world and she kept in touch with literally thousands of people. I dunno how she did it.

I mean, I know that when she came to stay with us, she’d get a stack of postcards and she’d write them all out, you know, and we’d have to go to the post office and send them off. But she was doing that all the time. She was doing that when she was at home and wherever she went, she was writing letters and keeping up this network of people.

And she would put people in touch, you know, they could give them that information. So she was, she was incredible like that actually. Wild. And another area that of her that I really appreciated was she has the most incredible memory. You know, she, she was a tireless researcher of matriarchal societies and cultures.

And that was her passion really. And she read and read and she traveled and she pilgrimage to, to various places, but she retained the knowledge. She, you know, I can barely remember what I had on shopping list yesterday.

[00:09:01] Risa: Right. Same.

[00:09:02] Annie: She had this like encyclopedic brain of everything that she’d read and researched and it was, incredible.

I mean, I think she was a genius in that, you know, she really was, and she could pull ideas together and she was never flummoxed or confounded by popular culture or what was in. She just was very solid grassroots sort of beliefs and activism. And she seemed to be able to get to the nitty gritty of things very easily.

I wondered if you could, I think a lot of our listeners will know some pieces about Monica’s show. Maybe they’ll have seen some of her art or they’ll, you know, maybe have heard the little bit of the story that we told in the podcast, but could you pull back and, and, and situate her work and her time?

Well, her parents were artists and although she never had an ambition to be an artist.

In fact, her mother had warned her, you know, two things in life. Don’t marry another artist and don’t become an artist. She had no formal training and she was a self-taught artist. And when she was about, I think about 16, 17, she decided that she did want to start working.

And so she was self taught. And I think in that sense, she kind of like bypassed all the usual rules of, you know, when you go to art college, it’s, you, you can do this, you can’t do that. And you know, all those things. So she was much freer to sort of explore than perhaps she might have been. If she’d gone through traditional art roots, So she left home, she ran away from home when she was 16, she had a stepfather that she really didn’t get on with.

And he wasn’t very nice to her. And she traveled off over France, Spain, Italy, those places. And she worked as an artist model for a number of years. And for her, that was like the epitome of women being objectified. And it put her off male art and the way that women are portrayed in male art and set her thinking on those ways of, well, how would I portray women’s lives?

And then she met her first husband and they had a couple of children. She moved to England where she then lived pretty much for the rest of her life. She was in Wales for about four years. But before that, she was in Bristol then she went to Whales. And she briefly had to go back to Sweden when her mother died.

It ended up being that she stayed there two years and it was during that period, she got involved in the Anti-Vietnam war movement and started being active in that, and started painting these early paintings, which people call her political period. But actually she was never unpolitical.

All her work is political. And she said, you know, the personal is political, the spiritual is political. So for her, it was all one thing and she never separated them. She painted these works that had very often sort of stenciled, writing text about patriarchy or women, and they were, in many ways, strident, angry, out there paintings. And when in 1961, she gave birth to her middle son Tovo for her, it was the first natural childbirth she’d had that she hadn’t had a good experience with her first child, but with the second one, she was at home and she, she experienced what she felt as the goddess.

And she saw these undulating waves of light and dark. And this huge power of her own body was evident for her. And that changed her life. Really. And she then started to paint about her women’s experience, giving birth and what happens with our bodies. The way that women are put down and subjectified or objectified in society. And she then exhibited that painting. she painted, God giving birth, which become a sort of an icon of feminists really. That painting was exhibited in 1960. I think it was 1968 originally, but then in 1972 or three, she exhibited it in St.

Ives in Cornwall and, and in Swiss cottage library in London, and there was a sort of out cry. She was threatened with prosecution for blasphemy and obscenity. And this was because the painting depicted a woman giving birth to the universe, to the world. And it was a black woman.

So it kind of went against all the, the social norms of the time. But for her, it was just her truth. And she couldn’t understand what, why would people be so against this painting and what was this big deal? And, and it was very traumatic for her because all her paintings were removed from the exhibition and they couldn’t be shown.

And there was this prosecution sort of hovering over her head in the end. She wasn’t prosecuted, but it did determine her to only to only exhibit with other women. And I think particularly to exhibit in more alternative galleries, So from then on, she did mainly exhibit with other women and she toured in, in Scandinavia and various countries.

And, really for the rest of her life, she tried to exhibit with other women and she always took her own route. she didn’t go into mainstream galleries and she was quite against mainstream art institutions.

[00:14:19] Risa: There’s so many seeds in there already that are so, so touching and so heartbreaking. I mean, She writes about, the trauma of having all her paintings taken out of that gallery and sometimes, I found in her writing and in her art, there was this sense of fury and anger and wisdom.

Yeah. But also, I don’t know, like a, like a sadness.

[00:14:44] Annie: Well, she became a sad person because she lost two of her sons after the tragedies of her sons dying. It was that heartbreak was always there and you could always see it.

And I think, you know, in later years she kind of mellowed, but when I first knew her enjoying those early years before her son died, she was, she was very angry. You know, she was really pissed off with the patriarchy, with the way that the world is run by men and how women are denigrated and pushed to one side.

And that came through in her painting.

It’s hard to imagine having the, the skills and the. I don’t know the energy or the, or the aptitude to be both, a writer, researcher, a visual artist, and an activist, a community builder.

I think that’s like a pretty unique personality that you can both make these stunning images and then really talk so coherently and, and in such depth about where they come from. I, I know for some artists I’ve interviewed, they’re like, I don’t words. Isn’t really my thing.

[00:15:48] Annie: Well, it’s interesting because I remember she said that, although she had very powerful visions that came to her, and she did believe that she was channeling Ancient matriarchal figures and that the sisterhood was speaking to her through the eons, you know, but she also said that, sometimes an image wasn’t enough and you had to spell it out in words.

And I think that was where her writing came in and she, she was able to spell it out in words, and it wasn’t even her native language English, you know, that must have been, even harder for her. I mean, she became very adept, but in the early years she made a few spelling mistakes and things in her paintings even.

But she mastered it. For her, the words, the talking, because she gave slideshow and presentations, and that was a very important part of her artistic practice.

[00:16:35] Risa: Do you have any insight into how she… fueled herself. I mean, I guess rage is a powerful fuel, but it burns out..

Yeah. I, I think more than the rage was this feeling that she had connected to the ancients and to something that she didn’t. I think she felt that, um, there was, there was really no such thing as time. So she was sort of able to tap into these energies and these matriarchal energies and other cultures that had existed that possibly in other realms still exist.

And she was able to bring that from there. And I think that was what nurtured and fueled her the possibility that, that, that could, be again, you know, that it wasn’t lost that it’s, it’s there for us. For feminists to create again, reconnect to, again.

And what was her spiritual practice like?

Well she was a pagan and she, she did partake in quite a number of pagan rituals, full moon rituals. That was important to her. She used to go to the sacred sites, particularly in Wales and in Britain anywhere, actually, wherever she went in the world, she would seek them out and sort of tune in to the energies there.

And not just once, you know, she made it regular that she would visit. I mean, for instance, Nevern and in Wales and Pentre Ifan Bobby Moore, the, the stones that are there, she often went and she tuned in and she would sketch or draw while she was there and gain inspiration that way.

She lived in a tiny flat, the walls were completely covered in images, postcards, pictures, you know, things that she loved from around the world. And every single wall, even the bathroom, you know, everything was covered.

So there wasn’t, there was no room for her to paint. So she had a, a number of friends over the years who let her use their spare bedroom or a room that they had in their house as, as a work, as a studio. So when she went there, she was on her own in the studio just doing the work. Um, so I, I never saw that really.

I didn’t witness the, that side of the, I mean, I did see her drawing and she did go into a sort of different space. She didn’t really want you to talk to her when she was doing it, or, you know, she didn’t need anyone else there. Hmm.

I just, I love to imagine her in this house covered in all the postcards and all the art, my house is very much the same. I guess that makes me wonder more about your vision for the archive. You have so much material and such important history about the women’s movement and such insight into how we do activism.

You know, she had such a powerful perspective on that. Like one thing that always haunts me about her in a way is she writes about coming out as a lesbian to the women’s group, and then receiving this rejection from this group of women that were really important to her and that , she had this. Queer identity that wasn’t very straightforward.

She, she was with men again afterwards, and she wrote about that being complicated and hard for her. She has this insight into women’s work and also queer work and, and so much of what the work still is right now… do you ever feel like she’s with you? Are you someone who has that, that sense of…

yeah, sometimes I do. And I sometimes ask her what she would want. And particularly if we are doing, you know, there are a number of exhibitions, which are, which there’s one in London going on at the moment, and there are some upcoming over the next three to four years.

And I it’s like the selection, you know, would you want that there? Trying to get some idea of, of what she would want, um, because she she’s been, I mean, we’ve been approached by sort of national museums and I’m sort of thinking, would you really want that? Would you like that? trying to, you know, answer those questions.

I think, for the archive, I mean, certainly in terms of the artwork, we are just trying to preserve and keep it in as good a condition as we can. And at the moment we’re offering out to, galleries and museums who are putting on exhibitions. So, for me, that’s great that that means that we can get her work out there that there’s this kind of revival of her at the moment. People didn’t appear to be interested in her for a number of years, but it’s sort of come back again and she’s, she’s currently being, looked at again.

I’m still going through all the archive boxes and archiving them. So I, I’m still getting a sense of what’s there. And I need to sort of finish that work, which is probably a few years worth of work, to itemize everything and see what’s there and get it into sort of some sort of digital format.

And then I guess, I don’t know, it’s no good just sitting somewhere, you know, and only we have access to it. So that needs to, to go somewhere where other people can access it. I definitely want.

To open that up at some point.

[00:21:46] Risa: It’s such an interesting experience. You’re living like years of your life now in, in these, in these, in these boxes, trying to document them and tell the story in tiny little storage units and things. Yeah. Right. Putting a life, trying to track a life that was so well tracked, but, but is also totally evasive in a way.

[00:22:10] Annie: Yeah. Yeah. It is it. And it, like I said, it’s the complex nature of it really, you know, it’s the fact that she had so many threads to her, um, and she wove this kind of amazing life and trying to keep it all on track or in the track. It’s. Hmm, that’s the challenge.

I wondered if you could talk about, um, she writes about that birth experience, and her writing about that was really important for me. , In my own, very painful, but, uh, I don’t know, revelatory birth experience, this, this sense that so many of the people you see walking around have had this incredible encounter with life and death, you know, that you it’s like you, you all went through this, like you’re just carrying this knowledge of this terrifying pain.

And then the terror you carry afterwards for your kids. Mm-hmm um, what do you think she believed about women’s power and, and what do you think she would want us to remember now in our activism, I mean, we have many Americans, uh, on, in our Covin and in our listener group who are dealing with this intense. Fundamentalism taking away their body autonomy. And that’s coming for us here in Canada as well from different political leaders.

I think she would be out there on the front line. Actually. We went to a pro-choice demonstration a couple of weeks ago after the ruling in America, and, and we said, then Monica would be here. She’d be in the front line here with us if she was still alive.

And she always believed that, you know, women, women are powerful, and that men are afraid of women in their power. So I think for her, she would be encouraging women to take back their power. I think that was partly why all her research into matriarchal times was so important because in, in those times she discovered that women were powerful. They govern themselves, they had autonomy, you know, they, they weren’t sort of downtrodden and treated by men in, in the ways that perhaps they are now.

Yeah. I love holding on to that, that image, you know, that there, there have been cultures that weren’t centered around violence. There have been cultures that were centered around. Yeah. And that the idea of a matriarchy isn’t just women. Doing the same fucking things that men have done, you know, a matriarchy had a profound equality.

Exactly. Nonviolent equality to it. Yeah, yeah. That we can reenvision I, and you mentioned a phrase, you said earlier, you said she, she didn’t believe in time. She believed that that could happen again and that it was here. Now, can you talk more about that ?

I think it was really just the, the concept of sort of multidimensional time, and space that everything exists in the now, including the past and the future. And so if you can tune into that as she felt she did, you know, she could access images and, Knowledge from those times from now that it’s, it’s here for everyone.

it’s difficult to say how that sort of played out in her internal life. I, I don’t really know, and it’s not something I discuss with her, but, I think her paintings do, when you stand in front of them, they do, they stir you, they do something to you that you can’t explain really.

Um, and I feel like it might be that energy that, that whatever it is that she’s tapped into comes through.

I certainly feel that. I mean, I, I go back to the Artist as a reluctant Shameka and that is one where I feel like.

Both the sadness and the sort of visionary quality, the layers of time, the layers of people. Yeah. And kind of what it costs too. Right. She put the word reluctant in there.

[00:26:31] Annie: Yeah. And I think partly that’s because of the death of her sons, she didn’t want them to die. She didn’t want to be forced into that position, but she had to question everything that she believed in.

She had to question the goddess and what, what, you know, why would the goddess do that? Why would that be something that needed to happen to have her sons taken away? And, and she, I think she, you know, for a time she lost her faith and wasn’t sure she was terrified of what might happen next and what the goddess might ask of her in the future.

for her, that was the, the reluctant part. And I mean, it took a long time and I know that she said that, uh, once her first out, like my first son was born her first grandchild, but that gave her hope again. And that gave her sort of a reason to live. But it, yeah, she, she took a long time to sort of come back to life.

She took a long time to paint again. Mm. And the, and the sadness was always there really, it was always present. And at the same time, I mean, I know that she knew that she was sort of in touch with them and that she would be with them again. But, you know, it’s that ki it’s that balance, isn’t it between our, our sort of human humanness on the planet and our, our dimensional sort of two dimensional sort of quality and, and our, and our spiritual dimension, trying to sort of bring the two together.

[00:27:54] Risa: Hmm. Yeah, it’s funny. You said two dimensional quality and I hadn’t quite thought of it that way, but I bet a painter thinks of it that way.

[00:28:04] Annie: yeah, I hadn’t really thought that until I said it. I dunno where that came from. thanks, Monica.

That in there. Right.

I mean, Monica was actually at the birth of my, my first, well, her first grandson, it was my third child. We were traveling in Portugal. We were living in a truck actually, and I couldn’t, I could no longer get into my bed because of my pregnant belly. So we thought, oh, better try and find somewhere to give birth.

And we found this, what we called a cow shed but it was this sort of tiny two room sort of shack thing in, up in the mountains, in, um, near Mon Chi in, um, she and Portugal. And we stayed there. Monica flew out from England. She wanted to be there. And, um, and I eventually gave birth there in this room.

It was a dark room. I mean, there were no windows in the room. It was, it really was a shack and, and Monica and Tovo were there and I, I gave birth, but I had, no, I actually had a similar experience to Monica. I had no sense of anyone else being there. Right. It was just me in my power with this huge force going through my body.

And Monica witnessed that as well. And for her, that was, I think that was, it just made it really special that she’d been there at the birth of her, her first grandchild. And for me, yeah, the same, it was, it was that sort of connection to the universe, to creativity, to, you know, all that stuff and, um, a very powerful experience.

Yeah. And, and, you know, people afterwards said, oh my God, you must have been mad. You didn’t have anyone there, you were, you know, how dangerous was that? And I was like, no, I knew what I was doing. and I, I wasn’t full Hardy, you know, I, I knew I’d already had to births, so I knew what to expect. I knew I’d set up sort of systems that, you know, if anything went wrong, there were ways to deal with it.

Um, but I just yeah. Wanted to do it on my own.

[00:30:04] Risa: Wild I love everything about that story. I was living at a truck, so I went to a shack in the mountains. did what I had to do connected to the universe. Yeah.

I would love to read the book that combines your obviously astonishing life story and Monica’s life story in the archives. I’m planting that seed with you for that book.

[00:30:27] Annie: oh, that’s interesting. Actually, because somebody recently said to me, you really need to write a book. And I, it was at this, the opening of the exhibition that’s currently on about with Monica’s work in it.

And, um, I was a little bit drunk and I went, yeah, wait thinking, oh my goodness. I’ve just agreed to write a book.

[00:30:45] Risa: you must, you must. Yeah. Yeah.

It would be good actually. Yeah. Yeah.

I mean, I think those are like, how do you find your way into a story like that? Right. Like you, like you say, it’s a, it’s a million tiny boxes in an archive,

that’s not the most accessible way into who she was, you know, but positioning it, as you said, you know, so beautifully quoting her, like the personal is political, the spiritual is political. Like we have to position ourselves. This is our, our opinion. Anyway, when we write is like, we have to position ourselves in the stories we tell, because we’re, we.

We’re filtering it. We, we come with bias. So if we aren’t honest about yes. Your lens. Yeah. Yeah. We, we have to say who we are otherwise we’re like hiding, hiding our distortions somehow. So what more powerful way to hear Monica’s story than, than through you, at least right now. It feels very, very powerful.

Annie, thank you so much. Yeah. Yeah. A friend of a friend of Monica’s actually Maggie. She, they were friends for many years and I am friends with Maggie and we, we are in contact all the time. We, we do things together and see each other and we regularly sort of get together and we, Monica will come up and we’ll be talking about, and we keep saying, we must record this because you know, there’s fewer and fewer people who knew actually knew Monica.

So we should be recording these stories and experiences. So. We must do that.

you must.

Maggie knew her much more in a political sense. So she knew her, you know, they worked together on things. She was one of the editors from the flames, which Monica wrote for. So she she was much more familiar with Monica’s politics at the time than, so between the two of us, I think we could probably write quite a decent thing

what a window. And, and like I say, I mean, it’s, it’s so relevant for us right now. Like we are, we have to. We have to continually find our strength as women to yeah.

Resist this strange desire. This dominant culture has to eat us and use us as product.

[00:32:45] Annie: Exactly. And it, it, it doesn’t actually seem any better. In fact, it seems worse than when Monica was alive . And that that’s true for women, but it’s also true for the eco side of things that she was an eco feminist as well.

World is still being raped and pilled and desecrated in the same way that it was then, so yeah, the work is still to be done to, to be carried on mm-hmm. Yeah.

[00:33:08] Risa: And in order to not despair in that we do need our heroes, you know, we need our warriors and, and she was really one.

Yeah. I would love to hear if you have any other stories or stories from traded from her friend about, you know, what she was like, what her, what her activist energy was like, or just a little, I don’t know.

[00:33:29] Annie: Do you know about when she invaded the cathedral with a group of, yes.

Please tell me that story. And then I will tell you all the different times I’ve told that story. Okay. I’ll tell you this. Um, want you to tell me the story? Cause I’ve, I’ve only read, you know, I’ve read descriptions of it that she wrote. I read descriptions of it that were written in obituaries written about her that seemed to not have the same facts as what she wrote.

And I have to tell you, so, um, Amy and I were, we are the co-producers of this podcast, co-author of the missing witches book. We were invited to a church to give a piece as part of an annual Gnostic conference. And it was about the divine feminine and we brought, queer and trans, practitioners of magic to sort of problematize the ideas that were being presented and, and to talk about women.

And we wrote about dance and we came into this beautiful old chapel in Montreal singing the burning times as a, as a way of honoring Monica and her work. And we told that story there too.

Well, she was part of a group belonged to a spiritual group at that time.

And I think one of the other women had suggested the action and Monica was a little bit nervous, but it was something she’d always wanted to do because she felt that the churches had stolen the places they agreed that they would go in and she was incredibly nervous apparently the night before.

And, and that morning when they went in, but really, really excited to go. So she’d made this sort of banner, which was her God giving birth image, and they took that into the church and they just sort of marched up the aisle really while there was a service going on and got to the top, uh, of the aisle and, and started.

I think they, I think they, first thing did, was start singing the burning times. And then they were interrupted by the, the priest, the Bishop, the vicar or whoever he was, who said, um, excuse me, we’re having a service here. And she said, yes. And so are we? And they carried on. And she said, she’d never felt so empowered.

You know, it was just amazing to do that because it was something she’d always dreamt up, but didn’t think she’d ever achieve. They sang every verse of the burning times and then they left and as she was leaving some man at the end said, oh, you, you are old enough to know better.

And she said, that’s exactly why I’m here. She had always wanted the church to apologize for what they did to witches. And that is, that had never happened. You know, she wanted to get a full apology from the church and like, you know, that still, still needs to be done. When she came out, she was just so ecstatic and just, they were all on this massive high that they’d achieved it and they’d done what they wanted to do and brought attention to, to how it was.

[00:36:24] Risa: I love that story so much because I.

I love the reminder that’s in the kernel of that story, that every action we take, you know, joyful singing, defiant, every demonstration, every time we come together where we can feel like, well, does that really matter? Does it change anything? It ripples like a, you know, it was an electric change for her.

It seems like it gave her joy, it gave her power, it tapped back into a power and then we still feel it. We read about it, it moves us, it moves us in our work

[00:37:01] Annie: yeah. And I think as well, she was also, she used to go to do, you know, you know, the green and women that there was a sort of USA Site where they, where they were having their nuclear missiles of put, yes, they take it over the common land and fenced it off.

And so there was a group of women who, who came from Wales originally and went on this March and ended up demonstrating at Greenham. But then they ended up living there. And over the years, I think 10, maybe 10 or 15 years, women sort of lived there and, and demonstrated every single day and Monica didn’t live there, but she didvisit.

I went on the 40th anniversary walk there actually recent last year in August a year ago. Because we recreated that March, and listening to the women there. There’s a fantastic website about it that sort of sense that very early on the women decided that they didn’t want men to be part of the action there because men would get, would probably incite violence, but also attract the violence from the police in the military.

And so their peaceful demonstration nonviolent actions would, would be the way that, that the women wanted to do it. And there was no leader. There was no, there was no hierarchy within it. So that played out over the years and, and how women organize themselves when they’re without men.

I think Greenham gave that sort of little glimpse into what a society of women could be like in terms of decision making and how things are done.

Hmm. So, yeah, Monica was part of that and I think that for her was really important as well.

Beautiful. I didn’t really realize that people had stayed and lived there for that long. Yeah. Yeah. They stayed until the, the missiles were taken away.

[00:38:47] Risa: Amazing. I love to imagine. You know, you have those moments where you have like a, a dinner party with women and you all just sort of, while in the midst of telling stories and sharing like incredibly emotional things, And I mean, I include my, my queer friends and my trans friends in this vibe because everybody can kind of do that dance.

And more and more, I do find I have, CIS men in my life that can adjust their energy to do this dance together. You know, while you talk about heavy emotional things, you also like. Improvise a feast. yeah. And there’s, there’s no, you didn’t make a plan beforehand, but everybody gently is doing it and you turn around and you’re like, oh, that’s a good idea.

And then everything is cleaned up in the same spirit, you know? Yeah. It just happens. Yeah. Oh, that’s those dinner parties for me are little microcosms of what I like to imagine. The future can be like yeah, exactly. Yeah. Everything taken care of without having to organize mm-hmm yeah. Yeah. That, that gentle consensus, that kind of just is a assessment moment by moment.

Oh. Is there anything else you wanna make sure, that we hear today about her or about your work? I’m just really excited that she’s being seen again, and that people are discovering her again and that she will have these amazing sort of international exhibitions coming up.

Cause I feel like that she was sidelined, you know, she was written out of the history books and, and her whole life was a struggle really to take her place. And I feel like now she’s taking her place. Mm. I hope that’s what will come out of it. Because she was such an important figure for, women and within all those movements that she was involved in the world and writing and activism and eco feminism.

Oh, that reminds me. I did wanna ask, do you have any. Insights into what the process was like for when she was doing this collaborative writing for the great cosmic mother.

Well, oddly enough, they didn’t meet for, I think it was 10 years. Wow. They never actually met. I was looking at, we’ve got this old VHS tape, and I managed to get hold of a player the other day . And we were watching it and there, it was the first time that they met, there was this interview.

Um, and , and it was quite storm. They’d been working on this book for 10 years and never met. So literally manuscripts were going back and forth across the ocean, you know, uh, snail mail and , and that was how it was done. Wow. So, and would they include like letters to personal letters to each other with the manuscript?

Yes. Yeah. Yes. They would be. Yeah. And I’ve got all those. Yeah. Wow. Yeah. Yeah, incredible really. totally incredible. And so did, did they have a friendship already or were they just respectful colleagues or I

think they were more respectful colleagues, but I haven’t read them all. Barbara Moore, was a poet and she was probably better with words. So, she had quite a hand in the format of it, but, the idea side would’ve been just as much Monica.

[00:42:12] Risa: I don’t know how much you’ve looked at the manuscripts, but can you tell, How that collaboration was happening? Like would Monica write pieces in?

Yeah, they kind of like, corrected each other almost, or, or would put notes in the margin, you know, what about this? Or add this or take that away or, or whatever.

So that would be the going back and forth, editing through what was written

[00:42:35] Risa: I love, if I’m writing about something, I just go to the index and see, if she’s got something for me in there, if they’ve got something for me there, you know, like give me a little, give a little new perspective, a little taste on something.

Oh Annie, thank you so much to you and your family for giving us this insight into this writer and painter and activist whose work means so much to so many of us. We’re so excited too, to see people discovering her and tapping into this.

Feminist warrior energy, you know, this gift of a feminist warrior energy, and also this image of her returning to these places and believing that those women that have come before us are with us still. Yeah. Those queer people, all those ancestors are raised, you know, erased from the archives in a way like you are doing this great work of, of digging into the archives for all those people who were erased.

So I know it’s taking over your life in a way, but what a gift, what a gift you’re giving us all. So thank you.

We’ll link to the website in the Instagram, in the show notes for this show, and we’ll find and link to the website for the Greenham women that you were mentioning. And just thank you again so much.

And thank you, Monica.

Brilliant. thanks to thank you so much. Thanks everybody. Blessed fucking be.

https://www.instagram.com/monica.sjoo/?hl=en

http://www.greenhamwpc.org.uk/

https://goddess-pages.co.uk/nevern-sacred-site-of-ceridwen-2/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mynydd_Carningli

https://cadw.gov.wales/visit/places-to-visit/pentre-ifan-burial-chamber