In this episode, I follow Maya Deren's light through my life, the string of the Witch's Cradle she wove, a story of euphoria and catastrophe.

Maya - named for the Goddess of the veil between - saw film as a form of magic — a ritual space where transformation could occur. A time medium.

Born in 1917 in Kyiv, Deren made her way to New York, working as Katherine Dunham’s assistant — supporting a Black woman artist whose study of Afro-Caribbean dance reshaped American culture.

She lived her myth: fiercely idealistic, driven to poverty by her devotion to the work, refusing to bend to Hollywood or to men who sought to define her.

Her partnership with composer Teiji Ito — whom she met when he was fifteen and she in her thirties — was both radiant and fraught, even those we revere carry shadows.

To honour Maya of the veil fully, we have to hold the contradictions: the brilliance and the blindness, the love and the harm.

When Deren traveled to Haiti on a Guggenheim Fellowship, she was possessed by the drums — literally and spiritually. She came seeking to film dance and found herself drawn into Vodou ritual, where the divine descends into human bodies. Her writing from this period — especially Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti — dissolves the colonial gaze, witnessing a world where the sacred and the social are intertwined.

Maya died at forty-four, her body weakened by poverty and amphetamines prescribed by the same “Dr. Feelgood” who supplied American presidents. Her death feels like an indictment that still echoes: of the machinery that devours visionary women, of the economies that prize profit over imagination, of the world that lets our bravest makers starve.

But through her films she continues to brush aside the veil.

She shows us that art is a mode of resistance, that ritual can remake reality.

She invites us into the totality of movement. She invites us to dance.

Transcript

We call in Maya, Daren. Witch of the lens. Maya, goddess of the veil between of the changes. The most important experimental filmmaker in history died broke and sick, wildly malnourished, using the little money she scraped together to feed her cats. She was Ukrainian and Jewish. She was a socialist. She thought she was going to Haiti to make a movie about dance, but in the form of the dance, she saw the whole metaphysical worldview.

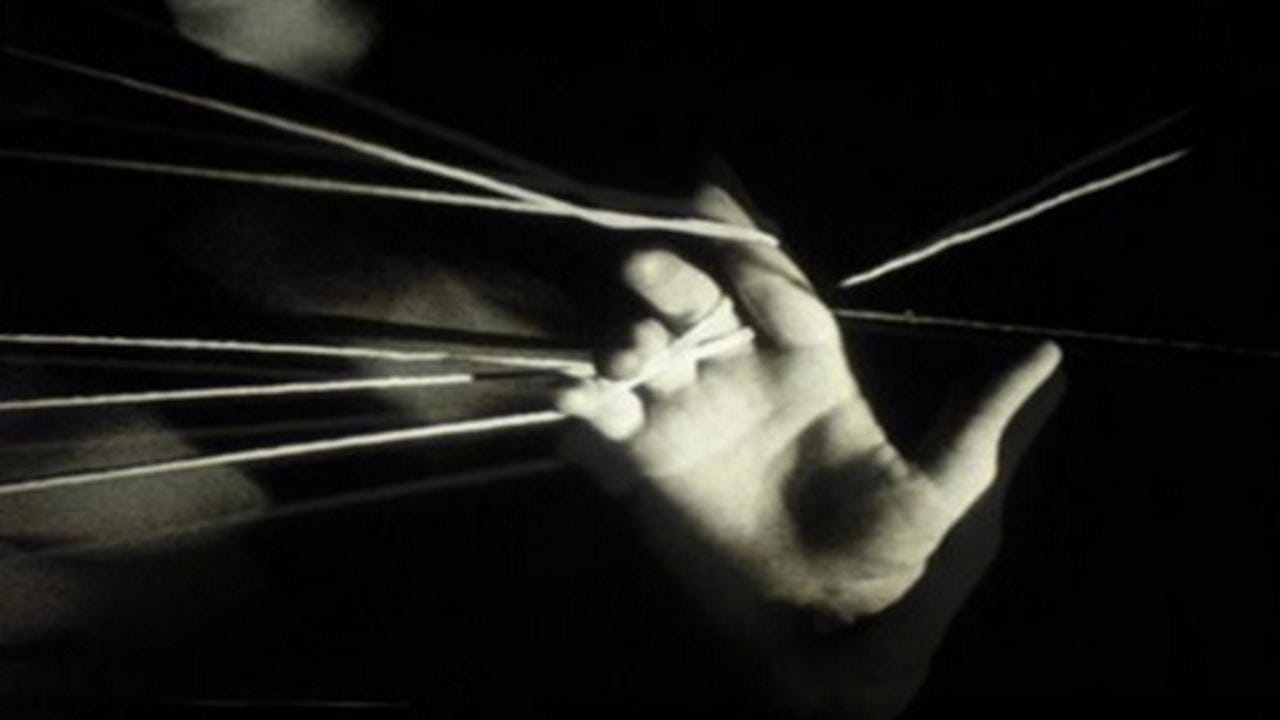

She studied possession. She became a channel. Her most famous film is Meshes of the Afternoon, but in a film called Witches Cradle there is a woman with a pentagram on her forehead, sometimes visible, sometimes hid by the effect of light. And around the pentagram reads, The End is the Beginning.

Sometimes being an artist or a witch is walking a teetering line between seeing magic everywhere, feeling yourself unspooled into the shining web of stardust, and then slamming back hard into the ground, the practical, the knife in the boot, pills on the counter, bills piled by the door. I guess it's more accurate to say that we always ride that infinity loop of changes, “god is change” as prophets Octavia Butler gave us, which is a way of saying change is the only thing, and the everything, the all-powerful thing, the infinite.

I think I told you already about the way fear hit my body and mind this summer, I slammed to the ground, got hit hard by the changes, I thought I was done cancer treatment then was told it had probably metastasized to stage 4 and spent weeks in the waiting place coloured by a slick fear that turned colours up to 11, then 11 million.

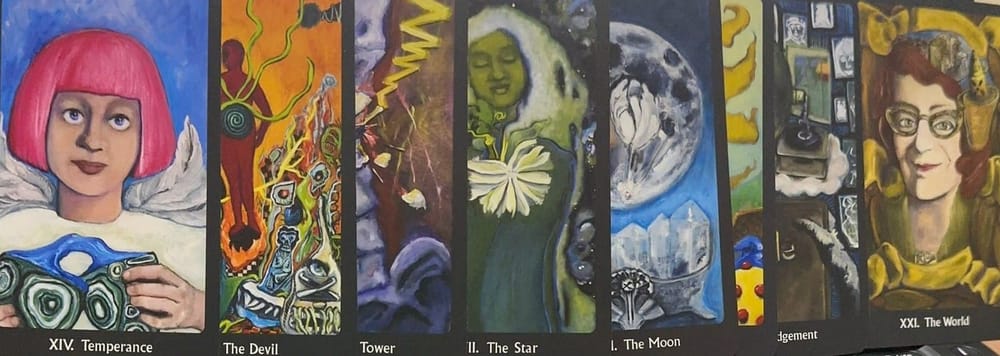

I didn’t tell you that during this time, whenever I pulled a card from the deck of ancestor oracles Amy and I had made with all the people our hungry witch selves had been missing, I pulled Maya Deren.

The message on the oracle card we created for Maya Deren reads,

“Where can you be an initiate at this time? Know that the soul of the universe is there waiting to meet you. Experiment”

One day I walked into the woods, lay on the ground on a sunny plateau, put on a drum track and listened to the leaves, the pearly everlasting growing around me, saw myself within a river, saw underground lit up by webs of stars. A man, a beloved ghost, rowed me to a dim shore and my friends met me there and we were kids and we just played.

I got up and did the rest of the hike in a dream state, everything was symbol and magic tinged, I turned left down into the valley my daughter calls Valley of the Queens instead of right up the path across the mountain, I found enormous granite stones left by “glaciers going home” as the anishinaabe word for north phrases it, encoding their 10 000, 30 000, 100 000 year memory of changes.

Under a stone bigger than my house there was an opening, wet and muddy, small enough to squeeze in and and lie under but i didn’t, i was afraid, i took a picture up inside and saw the wet underside of the stone was traced with glowing webs. I put my hand on the stone and felt a laughing voice say “you don’t have to if you don’t want to, it’s all out here too” then I opened my eyes and right next to my hand there was a perfect web, like a cartoon web, an archetypal web, four long lines intersecting like North-South, East-West and the crossquarters in between. I drew it when I got home. I tried to google it but didn’t get far.

Days later a package arrived, I had ordered a copy of Maya Deren’s Book “Divine Horsemen of Haiti” but two copies showed up instead, I laughed and texted Amy - Maya Deren is yelling at me!” And then I sat down and flipped it open randomly, and there on page 19, amidst notes on the translation of Haitian terms like Esprit and explanations of the use of footnotes in the text, there is, inexplicably, a drawing of the exact symbol. Four long lines intersecting - North and South, East and West, and the cross quarters. Beneath the image the words: “The cardinal points and points between.” With no other explanation. My jaw dropped. It was 1:11 on the clock.

Crying in the nurses office days before, gulping air, she had said “it’s so normal, it’s so normal what you are feeling, tu a perdue tes points de repairs.” I stopped her, and stopped crying, what does this phrase mean, point de repairs, and together we pieced it together - something like orientation. How you find yourself. Cardinal points.

Amy wrote about Maya Deren, and the woman who brought her to Haiti and introduced her to the psychology and philosophy of ritual dance in Haiti, Katherine Dunham, in our first book, Missing Witches: Reclaiming True Histories of Feminist Magic, in a chapter on Beltane.

“Born in Chicago in 1909, Katherine would become an incredibly successful dancer and choreographer - establishing and running the Katherine Dunham Dance Company, one of if not the earliest self-supporting predominantly black dance companies. She is hailed as one of the first African Americans to conduct anthropological fieldwork, and the first anthropologist to explore the function of dance in rituals and community life. All of her research informed her Civil Rights activism, raising Haitian dance out from behind the demonizing glare of colonialism and presenting it as a valid, beautiful and intense religious and cultural artform. Her book, Island Possessed, tells of Haiti’s history, how the island came to be possessed by the spirits of Vodou, and how she herself became possessed by Haiti - its people, its culture, its ritual dance. Katherine purchased a parcel of land there and adopted Haiti as her second home.

Katherine presented as fearless, and she used her bravery to change the world. In 1950, she was on a tour of South America with her troupe. Arriving at her pre-booked hotel in Sao Paulo, Brazil, she was refused service by the man behind the counter. Because she was black. Because the dance company surrounding her was all black. At this time there were no written anti-discrimination laws to protect Afro-Brazilians, but, undetered, Katherine Dunham went the very next day to see a Brazilian attorney regarding the racist incident. As a result, Congressman Alfonso Arinos de Mello Franco introduced a new anti-discrimination law in the House. Katherine’s refusal to allow herself to be treated badly, even as a guest, and her determination to make change, to battle racism in all its forms, ended with a law being passed to benefit Black Brazilians. It was the first law of its kind in their history.

As she got to know Haiti, its people, its customs, Katherine recognized that the vital and unifying spirit of Haiti came down to Vodou. She went to study the dance, and became a partner in the dance. She learned that the dance of Vodou goes beyond the body, beyond art and into the realm of the sacred. It was not just celebration, it was care. At one point she calls the days-long drum and dance ceremonies “bush psychiatry,” connecting these rituals to the mental health of their practitioners. And this is a Beltane lesson that we can keep for ourselves. Dance. Because it is not frivolous or sinful, it is self-care, part of Nature’s psychiatry. Eventually, Katherine was officially initiated into Vodou.

And so it also went for Maya Deren. When Katherine Dunham wrote her master's thesis on Haitian dances in 1939, Maya was her editor. She was an experimental film-maker who, inspired by Katherine’s work, first visited Haiti in order to make a film about ritual dances. She too found a truth, there, beyond measure. She found a belief system that resonated so deeply within her Ukrainian-born heart that she too became an initiate. Maya saw the dance in all aspects of Hatian life. In her book Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti, she writes of the country-side as a “theatre in the round, where a lyric dance drama of prodigious grace and infinite variety is in continuous performance.” From the pre-dawn dark, through the day and back into the night, Maya describes the “onomatopoeic rhythms and cadences phrasing” of market-bound women, the percussion of a donkey’s hooves. Beyond the ritual and ceremonial, Maya recognized the choreography of all life. Undulating waves.

She notes that a baby on his mother’s hip, absorbing the beats of a ceremonial drum will “know the drums’ beat as its own, blood-familiar pulse.” And we witches recognize this too - the beat of the drum, the beat of our pulse, the magic of dance in all forms: the natural molecular dance, the fun, ‘secular’ dance, the sacred, metaphysical dance that, as Maya says, “is a statement addressed not to men but to divinity.” Divinity, for Maya, is the Loa. She wrote: Just as the physical body of a man is meaningless, material substance, devoid of judgement, will and morality, unless a soul infuses and animate it, so the universe would be but an amoral mass of of organic matter, inevitably evolving on the initial momentum of original creation, were it not for the loa who direct it in paths of order, intelligence and benevolence. The loa are the souls of the cosmos. The lwa are the souls of the cosmos. So when we dance, we may dance in solitude, for our souls alone, we may dance with our soul mates, or we may dance as tribute to the souls of the cosmos. For Beltane, any form will do, as long as we are dancing.””

Let's always be dancing, at Beltane and at Samhain, as the veil thins.

Maya gave herself the name Maya in collaboration with her husband, Sasha Hammid, who said he gave it to her because Maya was “the goddess of the veil between reality and spiritual truth.” I say in collaboration because even if someone offers you a name, you need to choose it every day for the whole rest of your life for it to be yours. Even after they divorced, Maya stayed Maya, goddess of the veil between, of the changes.

And I swear I’ll start this story about Maya properly in a minute but quickly, before I forget, because everything is always slipping away from me now under the heavy water pressure of chemo brain and the crushing collapse of chemically induced menopause and, as I think I’ve told you before, my people were never steel traps to begin with, my mother told me once her brain forgets to protect herself. Here are things I want to remember to tell you about Maya all out of order before we begin: Maya was and is the most important experimental filmmaker in history and she died broke and sick, wildly malnourished, using the little money she scraped together to feed her cats before herself. She was Ukrainian and Jewish and had fled Russians and Nazis, she was a socialist, she was interested in what the choices about form said about an artist’s whole metaphysical understanding of the world.

She worked as an administrative assistant for Katherine Dunham, that’s how she got the job helping to edit her thesis, she showed up and asked if she could help her, learn from her, assisting a black woman in the 1940s, there are ways we can be portals, she played with the way film could capture dance and martial arts, she thought she was going to Haiti to make a movie about dance but in the form of the dance she saw the whole metaphysical worldview, and she knew she had to put the frame down and feel and witness, not commit the error of dissection but be an artist and be in this knowledge with every cell.

She studied possession, she became a channel.

She died of a sudden brain haemorrhage brought on by severe malnutrition and too much amphetamines, prescribed to her by the same Dr. Feelgood who would cause JFK to botch the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Her most famous film is Meshes of the Afternoon, but in a film called Witch’s Cradle - that she made with Marcel Duchamp - there is a woman with a pentagram on her forehead, sometimes visible, sometimes hid by the effect of light, and around the pentagram reads “the end is the beginning.” The film follows white string moving of its own accord, around the necks of men, a web stretching out from her hands, a web all around a room, a line that goes up and down and seems to descend forever.

And she wrote in a letter to a friend:

“Inside I am quite mad, emotional and sometimes, in little things, I am what I really am.” Sometimes, I am what I really am. “A little thing,” she continues, “like laying in the shadows of the lilac bush. Have you ever done it? Lain with your hair in the mud, and the cool torrent beating pounding relentlessly and ruthlessly on your naked body, pressing it into the earth from whence it sprang, blinding your eyes, choking you, taking you for its own, and then watching the lull, the end, the moon climbing up the tear-cleared skies, creeping stealthily inside, a glorious sin in your heart?”

We call in Maya Deren — witch of the lens, the mud, the lilac bush, socialist of dreamtime, fugitive from the machinery of capital. We call in the woman who refused to sell her visions to Hollywood. We call in the maker who saw film as ritual, rhythm as revolution. We call in her hunger, her poverty, her struggle, her failures, her vision. We call in the drumbeat of her reel — the rhythm that belonged to everyone. We call her as ghost, as teacher, as archetype, as one who lived possessed by the Lwa. We ask: what does it mean to make art together, in a world that keeps us apart?

Maya Deren was born Eleanora Derenkowskaia in Kyiv in 1917, a Jewish child of revolution and pogrom. Her family fled the violence of post-revolution Ukraine and settled in Syracuse, New York. Her father was a psychiatrist who treated the poor for free; her mother, a scholar and critic who read Marx and Freud out loud at the kitchen table. In Maya’s house, resistance was not abstract — it was how you fed people.

She worked for Stage magazine, a socialist theatre publication that believed art should belong to the people. She absorbed a conviction that would guide her forever: the work of art is not to replicate reality or sell a story, but to reveal what we already share — motion, rhythm, breath, a pulse.

Her socialism was both political and metaphysical. In her 1946 essay An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film, she wrote that art should not imitate the capitalist mode of accumulation — that its function is not to produce a commodity but to circulate energy. “The task of art,” she wrote, “is to create a space where time can be transformed.”

“The task of art is to create a space where time can be transformed.”

Witches, poets, artists, activists, listeners, Risa of the future I’m talking to you: Maya the veil asks us to remember, our craft is not product, is not content, is not slop to churn the wheel of capital — our making is a redistribution of attention, invitations into shared transformation.

In an essay published in Mademoiselle Magazine in 1946 titled Magic is New Maya wrote “more than anything else, cinema consists of an eye for magic - that which perceives and reveals the marvelous in whatever it looks upon”

And in a talk called “New Directions in Film Art” given in 1951 at the Cincinati Museum of Art Maya said:

“(A) child looks at the world through eyes like clear windows, really looking outward; then the individual needs to justify a history that has begun to exist with him, the window silvers over and thickens and thickens and finally we are confronted by a mirror in which we see nothing but ourselves, the affirmation of ourselves over and over again. We no longer learn; we see ourselves and we know it. For any human being it is important to try and keep as many holes in that mirror as possible. This is necessary in works of art because the experience of art is essentially and autocratic one; a work of art demands the temporary surrender of any personal system. The person who surrenders then possesses new experience. That is growth. It is the growth of travelling in another mind and knowing it.”

Let’s swear in Maya’s name to try and always reveal for each other the marvelous, to keep holes in our mirrors, to make bridges into other minds. What else is art or magic for?

I saw Meshes of the Afternoon in the small classroom at McGill University in Mtl when I was 20, a room with raked seating for 40, old wood up wrapping stairs, where decades later Amy and I would guest lecture about witches for a sociology class on deviance. Seeing Maya’s work floored me, gave me permission, let me travel into another mind, she was of only a few women whose work we watched that semester and even though there was no mention of her foundational writing on art theory of cinema, much less on the metaphysics, ritual and spirituality of Haitian voudou, the meshes of the afternoon caught me, the mask of light, the self looking back, the violence under the surface, and the power radiating from her, hung all around me, made me taller.

Later in grad school, I made films that followed the light in leaves, slowed down the bounding motion of loping down a green hill, looped my own gestures walking again and again in front of these french doors that opened out onto Mount Royal, floor to ceiling 5 stories up in the air, wrought iron and crumbling wood, the doors my dream self would go on to place in my memory palace safe space where all my inner journeys begin.

Maya’s been there for a long time in the way I notice light, and spirit gates.

I remember now, I actually first saw Meshes of the Afternoon before that university class, I took experimental film in CEGEP too, grade 13. We watched it on a TV screen in a stale griege classroom, and even then it hummed all down the hallway.

And that summer, in a backpatio covered with grape vines behind a brownstone in Kensington market, I sat with a friend all day drawing the outlines of the leaves’ shadows in bright chalk on the broken cement, and my friend said, said, you have a way of making regular days magic, and it was one of those compliments that shines through the deep waters of your whole soul because you feel like the most secret hope for who you could be is being seen.

And Maya was there too. Between dream and waking, reality and illusion, shadow and sunlight. In the Changes.

She wrote:

“Ritual in Transfigured Time is based on the manipulation of times. That film has no new objects in it and isn’t a new theme. It’s a film called Ritual in Transfigured Time because it is a reference to ritual and ritual in primitive society or any society where ritual takes place is known as “Rite de Passage” that state which means the crossing of the individual from one state into another - boyhood into manhood or as here widow into bride…

because film is a two-dimensional surface; but it is not governed as other two-dimensional surfaces, such as canvas. It is two-dimensional but also metamorphic. What is important is how one moment changes into another, how changing is constant. It is the changing of things, not the way things are. It is a time form…

I had been trying to extend into metaphysical extension; that film is changing, metamorphic; that is, infinite, the idea that the movement of life is totally important rather than a single life…

It is based on the Book of Changes [I Ching]... the basic principle of life is that the dynamic was the functional flow of negative and positive, repeated. ”

She made film as ritual, metaphysic film that draws us into the breath of infinite change, the great silver river as I’ve been calling it at night, as I literally try calling it to me from the shores of sleeplessness. The silver river is a film reel in Maya’s hands, the magic of changes that hold us beyond our daily strife, the feeling of resting my face in a river where I can still breathe and I dissolve but am somehow also more me.

I do not have stage 4 cancer by the way. I got the call the day after my 45th birthday. On the day of my birthday my neighbours and family organized our now annual flotilla party on the little silver lake with its underground river that makes us a community. We bring our canoes and kayaks and pedalos, even these funny floating docks with electric motors and muskoka chairs, and we pop bottles of bubbly and pass around snacks and jump in and out of the water and mouth fuck cancer together over the kids heads. And I felt the full euphoria, I felt healthy and held, and I knew it even before the call came.

But I still keep close the weird wisdom from those weird days when death was close: that the movement of all life is totally important, the dance, the sway, all our little life rafts tied together holding on, creating in our ritual, in our defiant celebration, in our art “a space where time can be transformed” and we open holes in the mirror of the self and are together.

In 1943, Maya made Meshes of the Afternoon with her then-husband Alexander Hammid. It’s one of the most studied short films in history — a dream spiralling on itself, a woman climbing her own stairs again and again, chasing and becoming the shadow that pursues her.

She wrote “what still inspires me the most is the capacity of cinema to create new, magic realities by the most simple means, with a mixture of imagination and ingenuity in about equal parts… to achieve on film the sense of an endless, frustrating flight of stairs, the great hollywood studios would probably spend hundreds on the building of a set. You, however, can do it for the price of the film required to photograph any ordinary stairway three times.”

Deren filmed herself as protagonist and subject, but also as archetype — the woman alone in the domestic labyrinth, trapped in repetitions of desire, work, violence, and self-erasure. In a letter, she wrote that Meshes was not surrealism but metaphysics made visible: “I make my pictures for what happens after the dream — for the waking that follows.”

“Deren’s work is most often viewed in the context of Surrealism… she was a friend of André Breton’s. Deren, however, denied any connection with the movement’s aesthetic aims. The Surrealist obsession with duality—with the lines separating the real and the imaginary, the rational and the irrational, the waking life and the dream—was, in fact, diametrically opposed to Deren’s fascination with the continuity of life and death, the physical and the spiritual, and “I” and the “non-I.” Talking about her film Meshes of the Afternoon, she stated that she was interested in the credibility of the unreal, not the incredibility of the unreal. “I am concerned,” she wrote, “with that point of contact between the real and the unreal, where the unreal manifests itself in reality.” Her films were intended as imaginary arenas where this point of contact could be visualized—where boundaries normally fixed could dissolve, or become wildly flexible; where protagonists could move freely between dreams and waking life without ever resolving the differences between the two; where nature and culture, urban and rural environments could be separated (and linked) by a single step; where past and future selves could meet along the road, fracturing into clones moving along parallel paths of time and space. Her years in Haiti, and her intense involvement with Vodou, can be seen as her quest to experience a living culture that gave “credibility to the unreal,” and thereby embody the vision she sought in her experimental films.”

In 1947, Maya travelled to Haiti and fell into trance. She lived among Vodou practitioners and abandoned the structure of the Guggenheim Fellowship that had sent her there. She wrote that she had to be an artist participant, not a voyeur, filming rituals and ceremonies no one else had been allowed to access.

In Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti the book, with its forward by Joseph Campbell, she describes possession not as madness or loss, but as collective embodiment — the body as open channel for gods and ancestors. She saw in Vodou a socialism of the spirit: each dancer, each drumbeat, each offering, an act of mutual relation.

For us, this is another lesson from Maya of the veil: to let the work take us. To be mounted by what we invoke. To trust that trance and art and politics are not separate acts but the same current flowing through different bodies.

She wrote: “In possession, the gods are made manifest through the flesh of the people; it is an economy of exchange, not domination.”

This was an anti-colonial, anti-capitalist revelation. In the West, spirit and matter are divorced; in Vodou, they are married through rhythm. To film that — to let the body of the camera enter the dance — was to make ritual through technology. She called her camera “an instrument of possession.”

Campbell wrote: “Maya Deren has performed the feat of delineating the Haitian cult of Vodoun not anthropologically ,,, but as an experienced and comprehended initiation into the mysteries of man’s harmony within himself and with the cosmic process….It is because Christians today recognize, painfully, the limitations of our Western tradition and are seeking earnestly some enlarged base for the formulation of a unified and unifying, yet adequately differentiated, understanding of humanity, that, suddenly - as though promising a revelation - mythology and folklore have acquired a new interest.”

We are more lost and fragmented, living more extreme class fragmentation, more obnoxious, destructive wealth and yet have access to more decentralized meaning-making and means of production than when Maya lived and practiced.

Deren refused the Hollywood studio system and instead built small communities of practice — salons, screenings, shared reels, teaching others to run projectors and discuss form. She toured the country showing her films, sleeping on couches, living off coffee and cigarettes.

Her socialism wasn’t rhetoric. It was praxis — an insistence that art should not depend on extraction or hierarchy. She once said, “I make my films for what money cannot buy.”

She dreamed of founding a filmmaking cooperative. She wrote that every filmmaker should own their means of production — cameras, editing tools, access to light — just as every witch must know how to mix her own herbs.

Note to self here remember: The tools of magic belong to no one.

The tools of magic belong to no one.

When we make art together, when we fund each other’s survival, when we share tools and stories, we are not merely making do — we are enacting the very future Maya tried desperately to capture.

“The arc of the story is this: a woman seeks to inhabit the world of the living and the dead. Her conviction is ravenous; her temperament volatile in the way that cool, clear liquid can ignite a lethal fire. Though she makes indelible contributions to her field, sustained mainstream recognition eludes her. After a streak of successes, she evaporates into a cloud of esoterica, sliding in and out of visibility in the decades succeeding her death…From today’s vantage, it is easy to see how blatant misogyny was taken up in what is essentially the tired refrain of Loosen up, Doll. For a particularly egregious example, see … Amos Vogel’s 1953 Cinema 16 symposium on “Poetry and the Film.” Of the five panelists (Arthur Miller, Parker Tyler, Dylan Thomas, Willard Maas, and Maya Deren), Deren is marked not just as the only woman, but as the too-serious, too-studious overachiever. Onstage, she is publicly mocked and viciously heckled by her male counterparts for her intellectual analysis of narrative poetics...

As the story too often goes with blazing women, Deren was ahead of her time for its majority, and then, in the blink of an eye, she was démodé”

By the late 1950s, Deren’s health was collapsing. She was receiving “vitamin injections” from Dr. Max Jacobson — “Dr. Feelgood,” whose amphetamine cocktails also fueled the Kennedys and countless celebrities. The same system that drugged presidents and botched revolutions fed her addiction.

Her hair fell out. Her nerves burned. She was still working — writing, editing, teaching — but she was being consumed by the same machinery she had spent her life refusing. She died in 1961 at forty-four, nearly penniless.

“To “get down in the deep” could be Maya Deren’s mantra. She lived life at breakneck speed, and she loved with “a terrible sort of love,” as though nothing was louder than the tick-tock of mortality, “because this is my only chance to have the world […] [to have] that sense of the sheer fierceness of being in the world, the sheer and exhilarating violence of living.””

Capitalism still feeds on artists until they die of exhaustion. The same sickness runs through our culture now — billionaires funding fascism while creators scrape for rent; the poison of productivity injected into our veins and marketed as self-care.

Our culture runs this message through us - the urgency, the time poverty, our “only chance to have the world.” What would a different relationship to the changes, to time on an ancestral scale, feel like in these bodies? How could we spread ourselves out into each other to find some ease, into circles that redistribute energy, attention, and love?

Her films over and over, seek to create a loop, she said she simed to create without climax, to make a lemniscate, to reveal the place of change that is everywhere, right there, within the mundane, the living spirit of generations of ancestors that can slip into us, the magic in every room.

Remember: Repetition is not failure. The loop itself is the spell. The return to the kitchen, the sickbed, the editing table, the broom, the protest — these are our rituals of redefinition, they are never done, the work is never complete, we are not defined by the fact that we always return, but by the threads that are endlessly weaving, the end in the beginning, the cardinal points AND the points between.

Even all this forgetting, up and down the stairs, wondering why I went there in the first place, even all these chemicals washing through the body, they are all coming with me on the journey, all part of the story now. Purity culture is bullshit, this is how I make my magic now, chemo, cracks and all.

We have to bring it all with us. We have to tell the truth about the fault lines and the failings of even our most transcendent heroines, the cardinal points AND the points between.

Maya met Teiji Ito when she was 30 and he was 15. He would become her last husband, they married shortly after he turned 18.

It’s so tempting to say but, but, but, they were creative partners, things were different then, gender dynamics in the 50s affected the relative weights of age difference, but we know this now to be statutory rape, an imbalance of power that causes distortion in the developing mind of the child, I look at pictures of my husband at 15, all awkward elbows and grins and trying to be a man, and I feel in my bones how unfair and harmful and not fucking ok this was.

Add to it that she expressed frustration that his inheritance was slow in coming, and she was impoverished and an addict by then. It does no good to waffle around it.

A culture that is sick and distortive reverberates through bodies with trauma and violation. This doesn’t excuse predatory behavior, lots of people live through trauma and don’t marry teenagers, but the constraints of the world narrow the field of possibility for all of us. We stop seeing the gateways and get lost in the hall of mirrors.

In Religion and Magic, Maya wrote about how Vodoun gives Haitian culture a stability that results in lower rates of sexual violence. She compares this to North America where each child has only their parents as a kind of god, in Vodou the Lwa, especially Erdulie the Lwa of love, lives through the parents and each successive generation and moves into the individual weaving them into collective relation.

In Stan Brakhage’s Film at Wit’s End, he recounts the story of their meeting: “...Maya had fallen very much in love with Teiji Ito, who was to become her third husband. They met under peculiar circumstances. One night, she had gone to a movie, and when she left the theater, realizing that she had lefty her purse inside, she went back looking for it. In the empty theater, she found a fifteen-year-old Japanese boy sleeping under the seats. He was Teiji Ito. She was quite shocked to learn that the theater 33 was his home: he would wait until the place was cleared out, then he would go to streets, panhandling. Teiji had run away from a well-off but oppressive family, to be a musician. He had no training, however; he hadn’t even had enough public-school education to qualify him for a music course at a junior high school level. But he had a natural talent, which Maya took on herself to bring out. Maya, in her thirties then, took him in and fell in love with him. They lived together for many years and were beautiful lovers. They began listening to music together. They would listen to Mozart, for instance, then to Haitian Voodoun music, and Teiji came to realize from the music of these various cultures certain possibilities which he could integrate into a style that would become uniquely his. It is Teiji’s music which was put on “At Land” after the film had run silently for many years. He both composed and performed. Brakhage, Stan. “ Film at Wit’s End: Eight Avant-Garde Filmmakers”, (New York, Documentext & Macpherson & Company, 1989), 106 (quoted here p. 32)

Maya and Teiji were complex people, like all of us, flickering, changing, remembered for their creativity and love and also for their failiures. Artist Wendy Erdman describes driving up the coastal highway with Ito so they could wash the airport off them in Muir Woods, laughing and playful, but also:

“There was a dark side to Teiji. He was manipulative, passive aggressive, often a bully, even physically abusive on occasion. I remember Cherel with a broken arm; Teiji once beat Dan with a shillelagh. Teiji nagged Jean into putting family members on the company payroll, sulking if he didn’t get his way. He was narcissistic and controlling, frequently moody and uncooperative, occasionally frightening. “Teiji Ito a memory” by Wendy Erdman, 2018 (unpublished interview)

So what patterns repeated, in their cells, in their gestures, in the roles of savior and violator and victim? If Maya and Teiji had been able to grow old in a world with love expressed through communal culture, communal witnessing to right and wrong, communal singing, dancing, mutual aid, feeding and caring for each other, tending to each other's spiritual and physical health, would she have slid off the edge of the dark the way she did?

I don’t know how Teiji Ito saw those days. He died suddenly of a heart attack in Haiti at the age of 47. But twenty years after Maya’s death, he completed her unfinished film Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti with his then-wife Cherel Winett. A work of return and restoration and reclaiming. He also created incredible soundscapes for Meshes of the Afternoon and other films of hers that had been silent. Theirs was a collaboration completed beyond the veil, beyond the individual and their flaws and breakdowns. In the end, he gave himself a voice in the work.

I wish it for all survivors.

The fact remains, Maya Deren redefined what film could be, and those films and her writing trace an outline, like the shadows of leaves, of another way that life could be. Her motion is still teaching us to move differently.

She showed us that to make art is to make ritual is to wage a quiet revolution.

As fascism rises again — polished, algorithmic, disguised as normalcy — we can look to Deren’s films, especially as completed by Teiji Ito, for another model of time: nonlinear, recursive, haunted but alive. They remind us that history is rewritten not just through conquest but also like a dance learned from wise friends, passed on to other bodies who carry on when we are gone.

We call in Maya Deren’s and Teiji Ito's courage and defiance. We call in the reel as wheel, time as tide. We remember her camera turning in small apartments, in temple courtyards, in the hands of the people. We call in the truth. We remember that she died possessed by the spirits she had once tried to honour:

According to filmmaker Stan Brakhage,

“Maya’s last film project, released in 1959, was “The Very Eye of Night.” It was financed by John Latouche, whom she had met when she was with Katharine Dunham in California. Latouche had been the lyricist for some of Dunham’s productions, and had since become famous for his work with musicals, including “The Golden Apples.” He had also become financially comfortable and wanted to help some of his artist friends. Maya was among them. He agreed to sponsor The Very Eye of Night. It tooks Maya years to complete this film, and the money went way beyond what Latouche felt he could afford. At some point, she was outraged that Latouche would cut her off, and so she put a curse on him. It is said that Maya had gotten into the practices of putting Voodoun curses on people who displeased her in one way or another. At least she believed that she possessed this power. That is the story, anyway. But in the laws of magic and Vooduon, certain principals operate. An important one is that if one becomes possessed by a god, the gods are responsible for whatever action ensues, but provided the possession occurs for one’s own personal reasons, the gods are blasphemed and may retaliate. The fact is that Latouche died of a heart attack shortly after Maya is said to have put a curse on him. And, so it is also said, Latouche had friends in a rival group of magicians who operated a curse against Maya Deren, stating when she would die. Maya Deren did die on a Friday, the thirteenth of October 1961, at age 44." Brakhage, Stan. “ Film at Wit’s End: Eight Avant-Garde Filmmakers”, (New York, Documentext & Macpherson & Company, 1989), 106

She couldn’t escape death or the exploitative, addictive, youth-eating, trauma repetitions of white supremacist imperialist capitalist patriarchy but she tried, and for shining moments she slipped through portals and saw a world where she could live otherwise:

Graeme Ferguson founder IMAX said of Maya,

“She came from the sea, if you’ve ever seen her film At Land, in her mind she was a sea creature, her bedroom was an underwater grotto full of shells, the ceiling was a painting of sea creatures, painted with phosphorescent paint, you really felt as if you were under the sea at night. It was an apartment of love, of beauty.”

Let’s hold up a cup for those moments, no matter how brief, when they were in that glowing place of love.

And for Maya who tried to get down in the deep, who lay beneath the lilacs, who danced until she was possessed who said “sometimes, in little things, I am what I really am.”

Breathe together now, and maybe you can see the cardinal points and the points in between, and feel each of us also listening, also caught in the witches web and the meshes of these afternoons, here in that breathing moment between the stone, beneath the lilacs - try not to slip down too far below to where the call of the magical loops around to becomes the mirror again - just breath here at the meeting place.

The film continues, the silver river shimmers on beneath.

The circle opens, our perspective lifts and its always been a spiral. The ritual isn’t over. The rite of passage has only ever endlessly begun.

Bibliography — Maya Deren: The Cardinal Points and the Points Between

Primary Sources

Deren, Maya. An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film. Alicat Book Shop Press, 1946.

———. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Vanguard Press, 1953.

———. “Religion and Magic.” Tomorrow: Vol. 3, No. 1 (Autumn 1954): 29–35.

———. Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film. Edited by Bruce R. McPherson. New York: Documentext, 2005.

———. “A Statement of Principles.” e-flux Notes. Accessed 2024. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/621433/a-statement-of-principles

Films

Deren, Maya. Witch’s Cradle. 1943. With Marcel Duchamp.

———. Meshes of the Afternoon. 1943.

———. At Land. 1944.

———. Ritual in Transfigured Time. 1946.

———. Meditation on Violence. 1948.

———. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Filmed 1947–1951, completed posthumously by Teiji Ito and Cherel Ito, 1985.

Secondary Sources

Barrett, Del. “Maya Deren.” Hundred Heroines. Accessed 2024. https://hundredheroines.org/weekendread/maya-deren

Durant, Mark Alice. “Sometimes I Am What I Really Am: On Mark Alice Durant’s Maya Deren.” LA Review of Books. Accessed 2024. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/sometimes-i-am-what-i-really-am-on-mark-alice-durants-maya-deren

The Marginalian (Maria Popova). “Legendary Filmmaker Maya Deren on Cinema, Life, and Her Advice to Aspiring Filmmakers.” January 23, 2015. https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/01/23/maya-deren-advice-on-film-letter

Ogawa, Michiko. Searching for The Cosmic Principle: Transcribing and Performing the Film Music of Teiji Ito. Doctor of Musical Arts Dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 2016.

Filmschoolrejects. “12 Filmmaking Tips from Maya Deren.” Accessed 2024. https://filmschoolrejects.com/filmmaking-tips-maya-deren-a6ddb39a6442

Wikipedia Contributors. “Ritual in Transfigured Time.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ritual_in_Transfigured_Time

Inverted Audio. “The Cosmic Music of Teiji Ito.” Accessed 2024. https://inverted-audio.com/feature/the-cosmic-music-of-teiji-ito

Risa Dickens (personal notes, 2025).