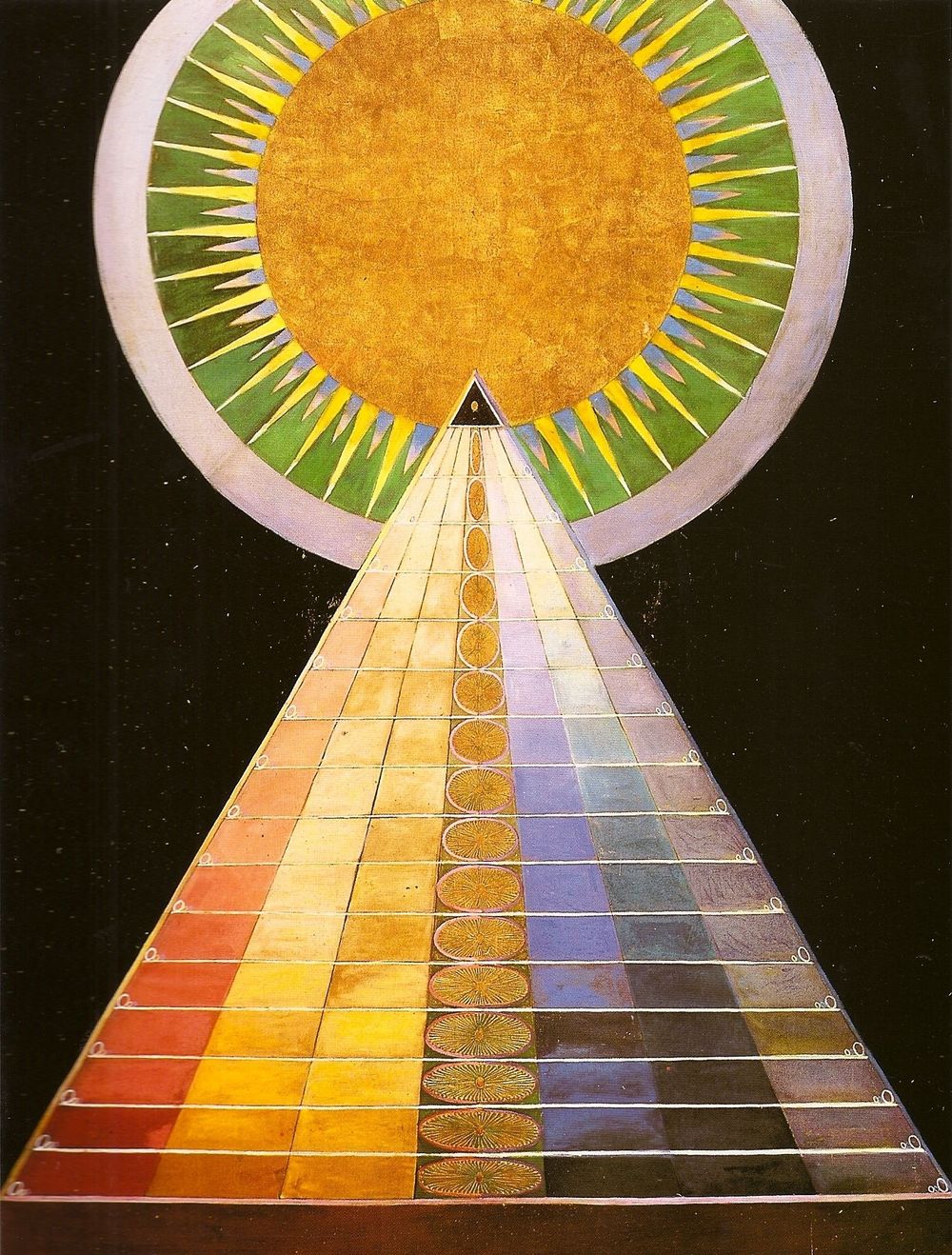

In this episode of the Missing Witches Podcast, Risa tells the story of the first abstract expressionist, Hilma af Klint, and her collaborator Anna Cassel. And the circles of women and spirits with whom they conjured a new vision of how the universe moves and what is possible. This is a queer story, an occult story, a story with love for the future.

This is a spiral story.

About hidden work that comes to light and changes the history of art which is the history of seeing, and of craft. This is a story about the shapes of the world, and the shapes of ideas. About abstraction and what it means to go seeking.

In this story, a missing artist, a Swedish woman named Hilma gets added to the pantheon of greats, it’s official! A woman painted the first abstract expressionist painting years before Kandinsky claimed that title. She paints for the future and she predicts it, and she is caught by it and finally celebrated. And then in an attic, in dusty archive, other journals by other women are found, artists, channelers, nurses, lovers point after point in this constellation is discovered and the story of the lone genius is up-ended, expanded, spiraled open. Genius has collaborators and they are interlocking circles of people and ideas. This is a story about emergent properties like love and inspiration, and beautiful beautiful beautiful paintings.

This is a queer story about care and authorship and so it requires new shapes.

This is a story about Hilma af Klint, and also Anna Cassel, Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, Mathilda Nilsson, Gusten Anderson, Thomasine Anderson, and more and more creative passionate women, flawed people, and hopeful, magical, powerful spirits both.

Hilma af Klint was born in a castle that had been converted into a naval barrack and military school, born in 1862 near Stockholm, Sweden. Her grandfather was the first person to map great stretches of the wild and rocky nordic coastline, he created nautical maps of what lay beneath. Hilma broke with family and social convention by choosing to study art, she was part of the first generation of women artists allowed to attend art academies, and the women had to pay more than the men. She studied and practiced at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm from 1882 to 1887. The women weren’t welcomed, they were mocked and harassed. They weren’t allowed to study or paint nudes with their contemporaries but Hilma did it anyway. At the Academy, she met fellow artist - and one of the great creative and emotional partners of her life - Anna Cassel.

Graduating with honors, the Academy provided her with a studio in the art center of Stockholm (shared with two other women artists), where she worked until 1908, mostly painting … landscapes and portraits, which she exhibited and sold (which she continued to 1914). With money she earned she took study trips to Belgium, Norway, Holland, Italy, and Germany. She also created many careful botanical studies of plants and flowers and worked as an illustrator at a Stockholm Veterinary Institute (1900-01). (David Adams.)

She traveled across Europe with Anna, alone in the museums and churches.

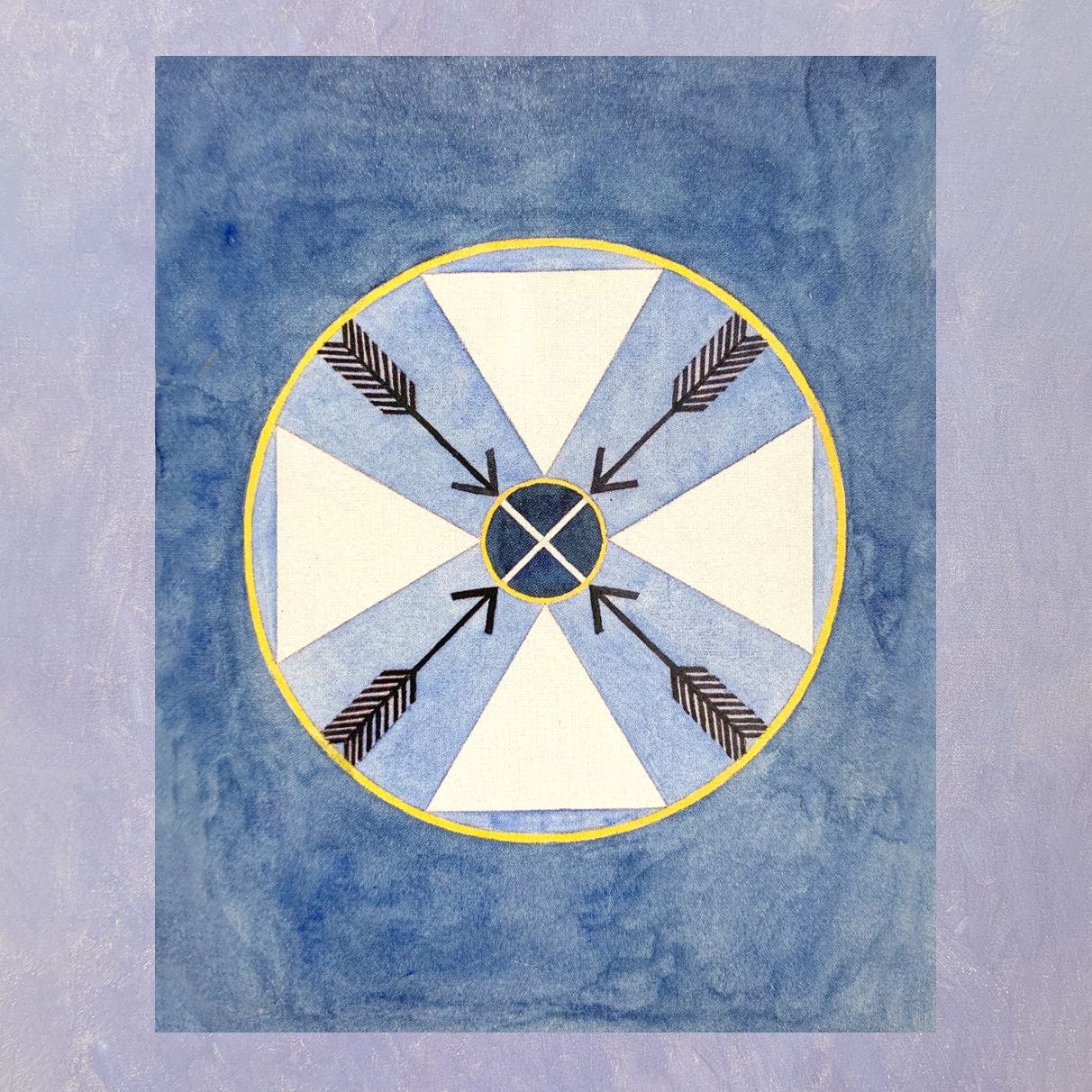

All this time, and for a decade in total, she and Anna met weekly with fellow artists Cornelia Cederberg, Sigrid Hedman, and Mathilda Nilsson. They called themselves The Five. They prayed and meditated and gave lectures to each other on what they were learning.

David Adams in Hilma af Klint – A Beginning Anthroposophical Commentary writes:

while kneeling around an altar with a triangle and cross… they contacted disembodied spirits and spiritual guides. At least one of the crosses they used on the altar was a white rose cross with a glass rose in the middle on a 3-level base, and they seemed to feel the communications and guidance they received was associated with the Rosicrucian stream. Taking turns serving as trance-mediums, they also received messages through a psychograph (an instrument to record psychic transmissions) and via automatic drawing and writing in pencil. Over time various messages, images, and symbols were recorded in a series of 5 notebooks and 9 sketchbooks documenting their weekly séances (books that af Klint kept her whole life and used as a resource).

Hilma brought a scientific diligence to the work of looking beyond, and she treated their ideas and images and discoveries seriously. In this way she built a visual language that would lead her to create what is now considered the first abstract expressionist art, although it feels like countless indigenous art traditions have to be ignored to make that claim. Better maybe to acknowledge that Hilma and Anna and their collaborators were drinking widely and deeply from their sources. This was part of how they practiced and prepared for the channeling. They studied world religions alongside their devotion to studying Christian and Lutheran spiritual philosophy as well as occultist movements including Theosophy, Spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, and Anthroposophism.

In 1889 she had joined the Swedish Theosophical Society (founded that same year) until 1915/16 and in 1920 the Anthroposophical Society, yet during the 1890s she also ran a Christian Sunday School on a family farm with a cousin. (ibid)

Hilma was already attending seances and thinking about maps and the sea and how humans have communicated with symbols when, at 18, her 10-year-old sister Hermina died of influenza. And for the rest of her life, she felt the boundaries between life and death differently, and her circles always included the dead.

When the 5 disbanded, she did not cease in this work of collaboration and investigation. We know now she had another circle, this time of 13, with whom she met and channeled throughout her life, even after members of the circle had passed. Perhaps she communes with them still.

Madoc Cairns, reviewing Julia Voss’s biography of Hilma for the Guardian writes:

Some were artists, others were writers, but all were adherents of the new philosophies sweeping Europe in the late 19th century: spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, theosophy. Mixing psychology, Christianity and Buddhism, historical fantasy and science fiction, “new age” ideals were amazingly popular, particularly among educated women, who used those ideologies to carve themselves new social niches outside the suffocating strictures of church and family. (…)

Her visions, speaking of secret pasts and a luminous, egalitarian future, drew others to her. And in this underground of dreamers and outcasts Af Klint found friends, allies and lovers. Like everything else in her life, the artist’s relationships with women were secretive, intense and suffused with supernatural meaning. (…)

Af Klint “experienced her sexual encounters with friends”, Voss writes, “from a place beyond clear gender relationships.

This is a spiral story. Hilma’s other-collaboration begins as a teenager, and she practiced diligently, for years, how to enter a channeling state, an open state to new thoughts - wherever you believe those comes from - and in that state she and her friends would draw shapes and write symbols.

This other-thinking led her to a life outside the dominant conservative Swedish culture, she bought a ramshackle house on an island, and had an expansive studio built where both she and Anna and others would work. She painted and lectured about spirits and science both. She cared for her mother when she went blind, and after her mother died she continued to live with her mother's nurse, Thomasine. After trying repeatedly to share her art - making traveling museums as she called them, fat books full of page-by-page documentation of the work, her hundreds of illuminated paintings speaking truths far ahead of her time.

Voss writes,

Af Klint had never expected to be understood by the art world per se. She had no ambition to exhibit at the Academy or in commercial galleries. She was not interested in buyers; she wanted an audience of seekers, people who would see in her paintings an alternative, a way out of materialism and toward “new thoughts” and “new feelings.” She wanted to open people’s eyes to the fact that life did not have to be merely quotidian, that the world was larger than what could be seen, that it was mutable and subject to transformation. Consciousness could determine being. Humankind could connect with the living spirit that she thought united all beings, from fauna to flora and even, as she pointed out several times, the mineral world. No one had to accept the cage of external reality. “The livelier the vibration of the thoughts,” she had written in 1919, shortly before setting off for Switzerland the first time, “the more flexible life on earth becomes, anyone will be able to work on matter with their imagination.” (Julia Voss, Hilma Af Klint A Biography, 257)

"The livelier the vibration of the thoughts the more flexible life on earth becomes, anyone will be able to work on matter with their imagination."

She made her work with the future in mind, because she believed in our ability to shape what the future could become. She worked with her great friends, great loves, to receive it and to create it and to try and share it, and finally to archive it all. They marked boxes of paintings to be kept closed for at least twenty years. They met in secret circles to study and teach and to listen. They worked together in support of a vision from beyond.

Channeling is a practice that supported Hilma and her community of women seekers throughout her life. What happens in those kinds of containers? Each person brings their own worlds of knowledge and experience and lays it down quietly in the background. And under the right circumstances, something emerges from our world's meeting. Something about how they put each other at ease, and also called each other’s background world forward, allowed for the possibility of something more.

In af Klint’s notebook entry from January 1, 1906, she wrote that one of her guides “presented me with a task and I immediately said Yes. The expectation was that I would dedicate a year to this task. In the end it became the greatest work of my life.” She was to depict “the immortal aspect of Man” and paint “a message to humanity.” She gave up her more realistic painting, underwent a ten-month “alchemical” purification to prepare herself involving prayer and fasting, and began in November 1906 at age 43 by creating 34 preparatory paintings as preliminaries to the major task, Paintings for the Temple. (David Adams.)

Hilma was 43 when the great project of her artistic and spiritual took shape, when she received and accepted her commission. Stop here with me, because I’m 43 and I need to feel that in my body. When I was younger I thought 43 would feel old but it turns out 43 has a “fuck it” vibe to it that feels surprisingly strong. At 43 maybe the kinds of people who assumed you wanted certain things have thrown up their hands at your weirdness, your failure, your otherness. Maybe they’ve decided they like you, or maybe they have begun to hate you. At 43, a woman can be terrifying to a certain sort of mind.

At 43, Hilma studied the universe and read and thought and met with others to talk about how it all worked and why, and when they hit the edges of what science had figured out - edges which were closer than they are now, but not by much - they experimented sincerely with means of looking beyond.

Kate Kellaway interviewed Hilma’s family for the Guardian, at the time of the Hilma af Klint retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery. Hilma’s nephew wrote:

She had intensely blue eyes. She was tiny – about five feet – which makes her full-scale works all the more phenomenal. She painted on the ground (Johan detected, on one painting, a small footprint – Hilma was here). His father judged her unsentimental, no fantasist – high-minded. A word that reappears is “resolute”. She was a vegetarian. Like Chekhov’s Masha, she always wore black. “Life,” she declared, “is a farce if a person does not serve truth.” She sounds formidable – not cosy at all. But who knows? Did she have a sense of humour? “Oh yes,” says Johan. (...) She never married, (…) women seem to have answered her emotional needs. Johan mentions Gusten, one of her group, who died. Hilma poured her friend’s spirit into her painting.”

According to Johan prophesy ran in the family.

She poured herself into her relationships with women, and she poured their spirit into her work.

And though she was treated as a quote “crazy witch” by the other inhabitants of the small wild island where she lived because they could not understand what those two women living alone up there were doing with all those eggs (they were making tempera paint, and they were painting.)

And though she did not find support for her work in the wider world in her lifetime.

And though she is buried in a grave that bears only her father’s name.

And though her paintings met with outright rejection by curators and scorn from reviewers…

Hilma and her coven and their astonishing collaborative communications were slowly and then phenomenally brought to light by her family and the community of astonished art lovers who rose up around this work:

The Moderna Museet (Modern Art Museum) in Stockholm - whose director in the 70s had rejected the work without looking at it upon hearing that the artist was a medium - hosted “Hilma af Klint: Pioneer of Abstraction,” with 230 of her paintings in 2013. It was the most popular show the museum has ever held, traveling to seven further venues throughout Europe, seen by more than a million people. The Guggenheim show dedicated to Klint in 2018 was the most-visited in its 60-year history. People waited in long lines. People wept unexpectedly.

And maybe what those thousands and thousands of people saw, what makes them cry, is that there is so much LOVE in them. Julia Voss writes:

Despite what people think, she would insist she wasn’t alone: she was moved by what she saw as contact with higher being, and there were two great loves in her life—the artist Anna Cassel and the nurse Thomasine Anderson. Without these women, the story told here would have been unthinkable. Without love, af Klint was convinced, there could be no insight. To achieve wisdom, she wrote in 1919, “two individuals must travel together, for the path makes it impossible for one person to proceed alone.”

She was sure we would read these words one day.

Af Klint never realized one of her most ambitious ideas. She wanted us to view her paintings in a spiral multistory building, proceeding all the way up to an observatory at the top. She called her sketches for this project “Designs for a Temple.”

The exhibition that opened in fall 2018 at the Guggenheim Museum’s famous Frank Lloyd Wright building came closer to fulfilling her vision than anything had before. Af Klint wanted a spiral-shaped building—an thanks to the Guggenheim, her works were shown in one.

Yet the temple building was only part of it. She also dreamed of a departure from the art world as we know it. She wasn’t eager merely for a place in the history of painting. Her works, she believed, could help us leave behind everything that makes the world small and rigid: entrenched thought patterns and systems of order, categories of sex and class, materialism and capitalism, the binary view of an Orient and Occident, and the distinction between art and life. (Voss, p9)

Hilma wants a temple in the mind, in the living temple of the minds of the future, as well as a physical place for us to walk through. She wants for us the love and freedom she glimpsed herself at times, I think:

When in 1912 she resumed work on the series of Paintings for the Temple, she steadily modified her method of working… Her contact with spiritual guides became freer and more personal. She said she had gone through an occult education to become independently clairvoyant and able to research spiritual worlds in a more conscious way. She continued to work serially and systematically, creating paintings in series with subgroups, numbered like scientific research. These works continued to explore a path toward a possible harmony between spiritual and material worlds, good and evil, female and male, religion and science. (Lightforms Art Center.)

She creates to chart paths toward a possible harmony.

The spiraling show at the Guggenheim comes incredibly close to matching what Hilma and Anna describe as the temple where these paintings belong, and it feels like the end of the story, the artist’s prediction is gloriously fulfilled and she is canonized, run credits.

But then Anna’s journals are found. They were in the attic of a house that had been donated to the Anthroposophical society. Hilma had edited her journals and archived her art, marking boxes with a plus and x symbol to indicate they weren’t to be opened for 20 years. As Sandra Huber told us in our interview, they were like a gift from her to us. We who are here now, in the future.

And the gift is incomplete without the works of Anna Cassel,

Hilma, Thomasina and Anna created albums, travelling museums, wherein each set of facing pages contain a black and white photograph of a painting alongside a small coloured watercolour of the same work, or sometimes of small details from the larger work, with dates and titles. (...) The images are numbered consecutively from 1 to 189. The title page includes the dimensions and dates of the original works as well as the attribution “by Hilma af Klint.” These specifications were written by Thomasine Anderson in red pen.

Together, the reproductions fill ten landscape-format albums with dark blue bindings. Three more volumes contain reproductions of Anna Cassel’s series from 1913. Photographing. Copying. Pasting. Labeling. Dating. Soon the Paintings for the Temple and Anna Cassel’s painted tale of the rose were available in miniature, in transposable and presentable format.” (Voss 225)

In The Saga of the Rose, the first publication of Cassel’s body of work, Kurt Almqvist writes one of the first-ever catalog essays for Cassel and says:

Anna Cassel’s special role in the group involved creating The Saga of the Rose, which is described partly as a group prayer book, partly as paintings that depict the past history of the world up to that point, while Hilma af Klint’s contributions were to be prophetic, consisting of future paintings. “To have received a commission from us; you have been assigned to create paintings for the prayer book, The Saga of the Rose.” Hilma also wrote “First section of WU is called the saga of the rose. That indicates that these paintings might have been done by or in collaboration with Anna Cassel, whose task was to create The Saga of the Rose.

The Saga of the Rose has been given to you, A[nna], to interpret. The two of us, G[usten Andersson] and H[ilma] have taken on the task of first attempting to interpret A and O, then the two OO, finally O and A, but A[nna], you have been assigned to investigate the notion that lies in the letter A. In a way, that letter contains the entire summary of our joint work [...].

Anna Cassel and Hilma af Klint were convinced that they were in contact with the Space Chronicle, the same work theosophists and anthroposophists prefer to call the Akasha Chronicle, said to contain mankind’s collective memory as well as future events. Anna Cassel’s task was to interpret the past, designated as ‘A’ in Hilma’s notes, while Hilma would do ‘O’, the future: Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.

Julia Voss has emphasized that the paintings were a joint effort, including those after the Temple series from 1915.

The collective’s work [at Munso] was to start with an eight-year period of research, when they would study that plant kingdom, animals and minerals. According to the promise, this work would help to strengthen their cohesion. As Hilma af Klint put it ‘Shared work premises; after that point, our work in not separate from one another’s. (…)

On 18 January 1914, Hilma af Klint wrote:

The Guru has a message for you, A[nna]. Your path is nearly ready for you. Your power will soon grow, and you will become a sturdy pillar like few others. You have been called as one and I as the other to erect the entry arch. (Almqvist 170)

I want the temple and the prayer book, I want the beginning and the end, I want to walk through both sides of the arch, don’t you? Isn’t it in the acceptance of the true wild spectrum of experience - all the rainbow and beyond of light and shade and identities and perspectives - where that possible future harmony might be found?

Isn’t it in the acceptance of the true wild spectrum of experience that possible future harmony might be found?

I want the temple and the saga of the rose. I want the full story that hovers just out of reach. I want to imagine the complex truths woven into the living text of everything.

A message directed to Cassel in 1900, and recorded in a notebook of The five, had already referred to this:

You should read the documents—not written by human hands, but engraved in the finest material of human life. For you should known this: For those who have eyes to see, there is a living text in everything, a diary of the changing fates of worlds, you are to look at the many lives of individuals as a fraction of this text.

The “living text” is given various names in the friends’ notebooks. Sometimes it is referred to as the “Akasha Chronicle” after a concept from Theosophy. Other times it is called “the Tale of the Rose,” connecting their task to Rosicrucian symbolism. (Voss, 135.)

Natalie Alder wrote in a piece called Hilma af Klint's Queer Clairvoyance for Paper Magazine,

If you are attuned to a certain frequency, you can receive the kind of queer future af Klint envisions. But if you are too mired in the here and now as opposed to the then and there, you might not pick up what af Klint puts down. Not everyone is clairvoyant. If most critics have brushed aside her queerness along with the mystical implications of her work as speculative concerns, at best, then perhaps not everyone is spiritually commissioned to receive her messages.

For Hyperallergic, John Yau comes close to calling her queer when he compares her decision to withhold her work from the public until two decades after her death to Emily Dickinson's own reluctance to publish her poetry in her lifetime. Both have been treated by critics as unsexed recluses, in spite of their respectively intense relationships with women.

And as with Dickinson, critics have treated af Klint's vision of the future as hyper contemporary and yet impossibly distant, a horizon that we can see but not reach. It's a familiar kind of future for queer people who aspire towards a liberation that would mean a form of life so radically different it is almost unimaginable. Over the rainbow, somewhere.”

Envisioned as stretching from the tiny intimate darkness of Anna’s Saga of the Rose paintings in prayer-book-form - a symbol story about the past, the origins - out to Hilma’s white spiraling temple of the future and all its lilac promise, this is a story about opposites, binaries, and the truth of all the shades and colours in between. Parallel lines meet. “Every atom has its own midpoint, but each midpoint is directly connected to the midpoint of the universe.” People identifying along a spectrum of gender roles and energies and performances and selves, people in respectful communication with the spirit of the land, each plant it’s own spirit as both Anna and Hilma meditated on and painted, letting love in all its variance lead to new kinds of life and freedom, all this and more is contained in the great vision of this work. I think that’s why some of us cry when we see it. It sings of our collective, longed-for, liberation.

Julia Voss suggests that Hilma and Anna connected with Theosophy as a “women’s liberation philosophy,” …“It said: ‘Sure you can be priestesses.’” And they were.

Anya Ventura wrote in Frieze Magazine, Oct. 2018 (quoted in Adams):

Why does af Klint speak to us in the present? Perhaps because she represents values – female, spiritual, ecological, collectivist – eroded by the rise of industrial modernity, values we desperately need to reclaim.

As hero webs of historians, detectives and translators work to find and tell us Anna’s story and the stories of this work from many more perspectives, they force the telling of missing values and practices. Values and practices for collaboration. For creating work that meets and crafts the future. Maybe even for liberation.

Halina Dyrschka, German film director and producer of Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint told the Guardian:

It’s easier to make a woman into a crazy witch than change art history to accommodate her. We still see a woman who is spiritual as a witch, while we celebrate spiritual male artists as geniuses.

When Dyrschka first saw Hilma af Klint’s paintings, “they spoke to me more profoundly than any art I have ever seen… It felt like a personal insult that those paintings had been hidden from me for so long.” (quoted in Adams.)

The story about Hilma isn’t simple. With Anna she saw herself in a masculine role but the descriptions of their relationship emphasize their identities as ascetic and virgin, the message from the voices they channeled emphasized purity. But in the journals of Sigrid Lancen, it seems Hilma’s desire arrives at a passionate next place:

Lancen writes:

July 28th, I felt a connection in those moments between my beloved Hilma and me that is the answer to the enigma of my life.

On July 29th, I was surrounded by H's arms, feeling an endless love so that we could die together.

On August 2nd, H and I sit next to each other. H, serious, embraces me gently.

On August 28th, I never lived so intensely, so truly in bright light with H's soul as in this time. (Voss 190)

Voss writes,

Was this the first time that the relationship led to kisses and embraces? Or was Lansen just beginning to record the experiences? As an athletics instructor, she would have been used to thinking about and describing the body. Perhaps for this the shared physical experiences. Six years had passed since Hilma was warned by her invisible companions not to “come to harm through careless touches, which S. L. N. instigated.” Four years had passed since the same messengers had urged Lansen strive to be the eyelet in order to connect with the hook, S. K. E. D. When the two friends came together in Lansen's bed, the warnings and euphemisms finally fell away. Physical love brought them closer to the mystery. The kisses and embraces passed into visions of raining flowers and light.

In her painting, she had already portrayed the man woman and woman man dozens of times as Ascot and Vestal, Islet and Hook, Blue and Yellow, as St. George or Parsifal with the Sword and Shining Armor, as Girl and Boy.

As early as 1906's Primordial Chaos, she had painted man and woman emerging from the shell of a snail, the hermaphroditic animal that unites the sexes.

The artist called her work The Fifth Gospel. (ibid)

She painted man and woman emerging from the shell of a snail, the hermaphroditic animal that unites the sexes. The artist called her work The Fifth Gospel.

This is a gospel that wants to offer us missing parts of ourselves. It sees both women and men finding paths and roles for themselves beyond the narrow, terrorizing, barbed-wire definitions of gender that had been constructed, just as whiteness was constructed, to enable tyranny.

Hilma was troubled by the tyranny and terror she foresaw. It had its choking roots around her - she had briefly been a member of the Edelweiss society in her youth, she attended seances with them as she worked on developing her own philosophy and practices. In later decades she would have been aware that women related to the group had become nazis. She studied Theosophy, whose founder Helena Blavatsky wrote of root races and was taken up by fascists on one side and social activists on the other. She was devoted to Rudolph Steiner and to Anthroposophy for much of her life, only turning away from the movement after Steiner died, when she felt she had a deeper personal connection with the spirit of the man. Steiner’s work and writings impacted millions of people working toward peace, liberation, and communion with land and spirit, but he said some stupid racist shit also.

This to say, then as now, stupid terrifying racist shit loomed and choked the air. Hilma and her twin soul, Thomasine, the sturdy love with whom she found the peace she had been seeking, felt the cruelty mounting around them as they worked, channeled and painted, in the years between world wars. Voss writes:

The Armistice of November 11, 1918, officially ended the war, but neither Hilma nor Thomasine believed there would be a lasting peace. Thomasine recorded a grim prognosis in the first of a series of notebooks written in German:

A new doctrine will arise, with selection as its core: everything which is physically weak must be disposed of, only those with normal physical abilities and intelligence will be helped forward. Strength, beauty, intelligence, and spiritual flexibility must prevail on earth. Animals will be seen as tools and mercilessly discarded when no thye are no longer useful. Behind these concepts are dark powers that want to convince people that the goal of a single lonely individual can be achieved. (Voss, 217)

In Thomasine’s vision, the dark powers were coming, and their progress was dependent upon the destruction of the weak, and of seeing animals as tools. spiritual flexibility had to prevail.

Hilma had dark visions too, Erik af Klint said:

In 1932 she made two watercolors in the shape of maps—one of northern Europe, the other of the western Mediterranean. They clearly represent the bombings of London and the battles in the Mediterranean during the Second World War (1939-1945)... She showed me these works many years before the war began. (Voss, 269)

They saw what was coming, and their response was to create a temple, a prayerbook, a set of messages for the future. And these were messages about the living spirit in all things. They were messages about the singing sacredness of life itself.

Hilma read Magic, White and Black by Franz Hartmann.

Hartmann wrote in the very first sentence: “Whatever misinterpretation ancient or modern ignorance may have given to the word Magic, its only true significance is The Highest Science, or Wisdom, based upon knowledge and practical experience.” Anyone who embraced this wisdom could set in motion that “spiritual powers” that all people possessed though few understood. This was the essence of mysticism. Spirit could move matter; it was more powerful than matter because it was the source and cause of all things. The beings who spoke to The Five were of the same opinion. In November 1898, Mathilda Nilsson received a message through the psychograph explaining the white cross. The symbol stood for “the descent of the spirit into matter—the rising of matter through spirit." (Voss, 102)

Professor Hanne Loreck describes Hilma’s paintings and the greater meaning of what they call her “thinking of progression and transformation” as follows:

“They are about the virtual in the sense of making operations of the Other thinkable, thus establishing a way of conceiving of nature and the supernatural beyond the dichotomies characteristic of classical thought and action.” (Adams, 57)

What makes the operations of the Other thinkable? How do we find a way beyond the classical dichotomies? For Hilma and her collaborators, the Other becomes thinkable by being honest about who they were, what they longed for, and who they loved. Following those movements, even when it hurt and the nature of relationships changed, led them through darkness to be there for each other. Anna and Hilma both found the loves that balanced them, remained collaborators, fought over money, and reconciled.

Julia Voss writes:

Anna Cassel died in 1937, at the age of seventy-seven. Hilma continued to interact with her oldest friend and confidant, her Vestal, her accomplice in breaking from The Five. … Hilma’s greatest loss, however, was Thomasine Anderson, who died on April 14, 1940 and was buried in Malmö. Hilma drew the grave in her notebook (...) (s)he wrote:

I will come to you, as soon as you call me, I will be happy. I want, when I fall asleep, for my right side to touch your left, and thus we will walk together toward the summit of the light. (Voss, 291.)

This is the season where we slip further and further away from the summit of the light. And there is something there, just beyond what I can see, where the darkness becomes the trees. This is the time of year when leaves fall one by one and each release is an individual step by a stranger in the night, and an individual sorrow, the sound is both hello and goodbye.

Witches, listeners, may the whispers and operations of the Other become thinkable for you. May you find the end point of the universe within you. May you find a partner whatever that looks like for you who can walk with you, each step a hello and a goodbye.

Picture Hilma and Anna two pillars of the archway, dark and light, the temple and the prayerbook, and picture all the people and beings they included in their embrace, the whole world of colours and stories, voices and ideas, orgasms and abstractions, calling to us past the edges of our isolation.

In this season, each plant drops its seed, hoping to find a new home, hoping that life will go on. This is all part of the living text, and in this way, we have our ancestors with us, in us, as we spiral from our deepest feelings and memories out into the great vibrating orchestra of it all. The living text that Hilma painted from insists, even in the face of fascism, misogyny, racism, ecocide, that we can end the loneliness and sense of meaninglessness that drives so many of us mad, we can make a safe and joyful place to land.

We can still follow the call of love, and walk together to the summit of the light.

Works Cited

Voss, Julia. Hilma af Klint: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022.

Kurt Almqvist, Daniel Birnbaum, Hedvig Martin. Anna Cassel: The Saga of the Rose. Bokforlaget Stolpe (April 18 2023)

https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/who-created-the-paintings-for-the-temple/

https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/group-i-primordial-chaos-1906-07-by-hilma-af-klint

https://www.kanopy.com/en/banq/video/11154107

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/28/arts/design/hilma-af-klint-legacy.html

https://bokforlagetstolpe.com/bocker/hilma-af-klint-the-art-of-seeing-the-invisible/

https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/who-created-the-paintings-for-the-temple/

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/pharrell-acute-art-hilma-af-klint-nfts-stolpe-1234646756

https://footnotes2plato.com/2023/05/20/rudolf-steiner-and-racism/