In our second interview with writer Nadra Nittle, we pick up our conversation about the syncretic spiritual philosophies of Black Women luminaries.

In episode 107, Nadra Nittle talked about her book Toni Morrison's Spiritual Vision: Faith, Folktales, and Feminism in Her Life and Literature and shared insights into the ways magic worked in Morrison's family, personal life, and fictional worlds.

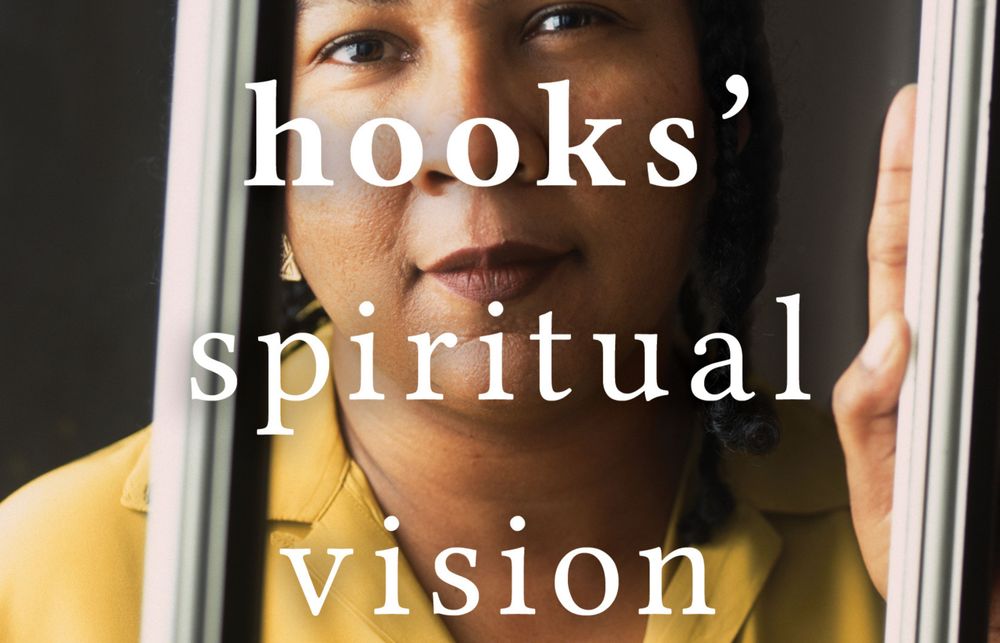

This time Nadra brings a new book - bell hooks' Spiritual Vision: Buddhist, Christian, and Feminist - and new insights into lesser-known aspects of bell hooks' thinking.

Nadra emphasizes the empowering and active quality of bell hooks' take on spiritual practice, and on love. Especially for Black Women, bell hooks urges her readers to create a spirituality that heals. She considered herself a Buddhist Christian, but Nadra identifies a pagan, witchy thread through the work as well.

hooks believed in a kind of love that could ask questions, love truthfully. Love as in being committed to the other's spiritual development. In this episode, Nadra and Risa talk about what a love like that might really mean, and how it might help us all heal.

Transcript

[00:00:00] Risa: I am short of breath today. You might hear it in my interviews. I just dragged a rubber pipe off the mountain that I found up there while I was on a hike and I've been sick for a week and the asthma is a pressure on me. And it sort of feels like the sorrows of the world are symbolized by the rubber pipe I dragged out of the mountains today.

But I'm so excited. I feel like when we get To have a guest come back on the podcast. It's a sign that we're doing something right, that they're willing to come back and talk to us again. And I love Nadra Niddle's writing and research so much. I think it's such a gift, the work that you do, the incredibly thorough work that you do to position these luminaries into their context.

And so I'm just thrilled that you're here. It's fun to get to talk again about your writing and your work. I wondered if you could start. Maybe do your reintroduction for the folks who didn't meet you last time when you came to talk about Toni Morrison and your book. and also I'm so curious about this idea, now you have two books about spiritual visions, I wonder about that project for you. We can talk more about it. Hi, and welcome back.

[00:01:21] Nadra: Thank you. Thanks for having me and thanks for your kind words. I really appreciate it. And for having me back. So, yes, I've written two books. About two different black women's spiritual vision. So the first one was Tony Morrison's spiritual vision, and this one is on bell hooks spiritual vision.

So the late feminist scholar, cultural critic bell hooks, who sadly died about two years ago, it'll be two years ago in December. And I got started on this project because a magazine editor reached out to me and asked me if I would be willing to write about spirituality and Toni Morrison's books.

That year, it was the 30th anniversary of Beloved and the 40th anniversary of Song of Solomon. And so in light of those anniversaries, they asked me to look at spirituality in those books and in Toni Morrison's life. Well, I think about two years after that, a publisher Fortress Press reached out to me and asked if I would be willing to write a whole book about Toni Morrison's spiritual vision.

And after that book came out two years ago they wanted to know if I wanted to do a follow up and they had some suggestions of various men, but I wanted to do another woman bell hooks had just died and I thought she would be a good person because I knew that she was a Buddhist and that played a big part in her work.

And she was also a Christian she identified as a Buddhist Christian and so that's what this book is about it's called the full titles bellhook spiritual vision, Buddhist Christian and feminist what the subtitle doesn't get at is that. Bell Hooks was also a little witchy. She didn't identify as a witch, but she, she believed in magic and she did do some witchy things.

[00:03:24] Risa: It's interesting to write these works at the invitation of someone else. So you're sort of being like called in, in a way, right? Like, come tell us this story. And there's, you know, there's the assertion from you, like, let's not, let's not deviate and do a man just yet. Like, let's do another, let's do another woman.

But also, do you think about a spiritual vision? Like, why does it matter that someone had a spiritual vision?

[00:03:53] Nadra: I think it's because spirituality is often downplayed, like Toni Morrison, for example, was a Catholic and I don't think that many people knew that she was a Catholic and what role that played in her work. But once you start reading her work through that lens, you see a lot of Catholicism. I also think Toni Morrison, right, was also a little witchy and her family believed in, in ghosts.

She was told ghost stories when she... Was growing up and some of those stories make their way into her books and same thing with dreams and I think bell hooks is actually pretty similar. I don't know so much about the ghost stories but in terms of African American folk magic who do there's a part in the book I talk about how you know they believe that hair had magical.

Towers and you had to be careful about who had access to your hair. She worked in her aunt's salon and her aunt was just a very kind of by the book Christian and didn't believe in, in folk magic or who do didn't thought it was all nonsense, but bell hooks and her siblings were like, no, we believe magic is real.

And our customers want to make sure that our hair is either swept up and like burned or otherwise like, kept, you know, out of the way from potential enemies. And so she had a unique spiritual vision and just in her upbringing, she was also as a young child, you know, a pretty devoted Christian. But because she thought You know, the Christianity, especially of her church was very patriarchal and the word she also used was fundamentalist.

She was drawn to Buddhism because she thought that there were more, I guess, roles for women. And she also with Christianity, she was drawn. I know you just recently had a had someone, Christina Cleveland, who's really into the Black Madonna. So bell hooks was also, really moved by the black Madonna.

So she really was interested in the divine feminine. And I think that played a role, not just in her life and upbringing, but in her work, like when she was writing, she believed that kind of You know, her ancestors were, were guiding her they were guiding her words. So I think it's important not to overlook spirituality.

[00:06:18] Risa: Right, I mean, and I, I love so much you describe that moment, students coming into her office. Like broken hearted and her feeling like I have to tell the truth like I have to tell the truth about what gives me strength Can you give us more insight into how? She combined spirituality in a way that gave her some liberatory strength that helped her express this like powerful vision of love that she had that was love in action, right?

And that the way she drew on multiple faiths to ground that in activism is something I think we need to learn a lot more about from her, right?

[00:07:00] Nadra: Yeah, I mean, she was not just interested in religion for religion's sake. She believed that, you know, religion or spirituality. Had to go hand in hand with social action, and if the social action piece was missing, she wasn't really interested in it. So, in terms of Christianity, she was really, in addition to the Black Madonna, she was really influenced by the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.,

and how he, right, obviously was, like, leader in the civil rights movement, and had, you know, whetted his, his beliefs. With social action on the Buddhist side. Think not Han the Buddhist leader. She was really drawn to him as well. He was outspoken against the Vietnamese war and actually Martin Luther King and think not Han, you know, actually met up at one point.

So her spiritual influences met each other and think not Han got Martin Luther King To come out publicly against the Vietnam war, which was not a, you know, a popular position and could have created a backlash. And so she was, she was drawn to those men, but she was also 1 part 1 version of the book.

It needs to be updated that I don't have, but her original, the reason she became drawn to Buddhism is because she met a few Buddhist non nuns, and she was really drawn to them. And so that is what really made her interested in becoming a Buddhist. So I do think women, you know, played a role in her, her becoming a Buddhist.

And I think in terms of Christianity, she grew up in Kentucky where she had. And aunts and grandparents who were really practicing right African American traditions you know, derived from West African spirituality, and they kind of mix that with Christianity and some of her elders. They didn't go to church.

They weren't church going Christians. They thought the church was kind of hypocritical. So all of this kind of played a role you know, and who, who she was. Her work and what she believed in. And I think the other thing really quick I forgot to say is that, you know, she, she was born in the early 1950s.

So she was, she lived through desegregation of schools. She, she was part of the first group of students who had integrated her high school and it was a very painful experience. So I do think her social activism, Yeah. It dates back to that experience. And in terms of her church, she was really offended by the fact that girls were told that they could not cross the pulpit, but boys could.

And she called that like an early induction into sexism. So that, and, you know, girls should wear dresses and, and, and other things that she learned in the church made her come out against sexism, capitalism, et cetera.

[00:10:08] Risa: Can you talk more about Liberation theology, like what that means and what that meant to her.

[00:10:16] Nadra: Yeah. So, I mean, liberation theology, I think, is a way for different oppressed people to kind of find themselves specifically liberation theology is usually discussed in terms of Christianity. So, if, if you're a woman, for example there's a feminist theology and, and it gives you a way to look at, Christianity through a feminist lens, as opposed to looking just at the men in the Bible or looking just at Jesus, you would look at the many different women who've played a role and these religions and.

You know, bell hooks herself. She was she was really influenced by Julian of Norwich, who is believed to have written she was around in the 1300s. And she's believed to be the first woman to have written a book in English. And in that book, which is, which is a Christian book. She talks about God is being.

you know, our mother instead of our father. And so when bell hooks read that, I think she might have read that for the first time as a teenager or just, you know, very young woman. And she was really moved, you know, to hear God referenced as a mother, as opposed to a father, which is what she had grown up with.

So And it's not, and I think in addition to just, like, looking at Christianity through the lens of the oppressed, whether it's women, whether it's black women, you know, it could be Latinas children, there's child liberation theology, which I write about, and there's queer liberation theology. So it's a way for oppressed people really to see themselves in Christianity.

But it also is saying, I think what bell hooks did, which is that. Christianity needs to serve to liberate the oppressed. So if you're a Christian, that should be part of your faith is helping other people get free, essentially. And I forgot to mention, I guess. One of the biggest liberation theologies, which is Catholic Liberation Theology.

And that played a role, you know, people were using that like in, in Latin America and, and revolutions in, in different countries. So yeah, it's, it's a pretty serious look at like basically saying you have to, you have to fight. You have to fight to get other people free. It's not enough just to have faith.

[00:12:46] Risa: I find really like, I don't know, reassuring and electric that, that it was not just, okay, we'll find our way through Christianity, not just through this particular paradigm and set of rules that will just like concede the ground, like this is the true access to God, but I can find liberation through this.

But also to say, It's not just this one path like she said she wanted people and especially black women to have all the paths that you could have Buddhism, you could have paganism, you could have animism. Can you talk more about how she reconciled these really different worldviews or if she did?

[00:13:27] Nadra: Yeah, I mean, I think she was just kind of a maverick and she just kind of, you know, defied the rules really early on, because I think now in the 21st century, you have lots of people kind of doing what she recommended. I think she mentioned this in a book that came out in the 90s, you know, and now we have people saying, I'm a Christian witch, I'm a Jewish witch, you know, like, just mixing things together.

And that's fine. But I think 30 years ago, that wasn't so fine. And I think even today, if you were to say, you know, I'm a Christian, which some, some people might you know, be offended by that. But right now, we're in this moment where the Pew Research Center does say the fastest group of people, they identify as.

spiritual and not religious. And so people are kind of defining religion on their own terms and bell hooks was a trendsetter. She was trying to, you know, heal herself. She had a pretty traumatic childhood. I talk about kind of the corporal punishment that she experienced as a young child just for, you know, for being different.

She was kind of the scapegoat of her family. And so she wasn't affirmed as a child. And so I think she was interested in how Christianity could heal her, how Buddhism could heal her. how aspects of paganism could heal her as well as I would say humanistic psychology. So some of my book looks at that as well.

I mean, she was definitely into psychology and self help. I think she thought black women had been so burdened with taking care of other people, you know, and focused on work and just survival that spirituality was not the focus and I think she thought for black women to heal.

They had to engage spirituality and not patriarchal or fundamentalist Christianity. But, you know, a healing spirituality and if that meant someone thought, Hey, you know, I think Judaism is healing for me that that was fine. She didn't want people to be boxed in and she didn't box in herself.

So I think that was really radical. I mean, she was a radical feminist and I think her approach to, to spirituality and religion kind of reflects. How radical she was, because you think about, the black church which bell hooks did criticize, for it being patriarchal.

And she thought that some black women felt like they couldn't go outside of the black church.

[00:16:10] Risa: Both she and you actually in this book. Like, criticize, or bring theory, or bring critique, as though it's part of the love. Do you know what I mean? Like she, she, she's like, she's willing to talk about Beyonce, for example, and like things that are powerful and magical and radical about Beyonce. And also like, there's, well, you know, you're the one who brings this to the conversation, but like that there's a lot of capitalism and like a lot of love and glorification of money in some of those songs.

And then she sort of talks about violence, like she's such a committed. Nonviolent writer thinker activist. She's not willing to just sort of look past the moment that Beyonce embraces violence Feeling that like maybe power that comes from smashing things.

She's not willing to look past that She's like, I love you, but let's talk about it. Can you talk about love and telling the truth love and critique?

[00:17:08] Nadra: Yeah, so bell hooks believe that, critique was a form of love that she critiqued in love, even if it enraged people and her critique of Beyonce different parts in the last decade of her life really led to this long lasting backlash. That was brought up right after she died. And even today, there are people who are still very angry that she criticized Beyonce and just to give listeners a little more context.

She, she critiqued Beyonce for two different things, but one was Lemonade, the visual album. If you've seen that there is one scene where Beyonce is wearing this yellow designer gown, she's a woman scorned in this video, and she's walking around with a baseball bat, and she's bashing cars.

bell hooks criticized, I guess, that version of feminism as not being liberatory because As a Buddhist and even as a Christian, right? The two men that she was influenced by were dedicated, you know, pacifist and she was a pacifist as well. She looked at violence is a form of patriarchy.

She sees that as a woman kind of embracing patriarchy in that moment, and she didn't believe that patriarchy or dominance, another word she used a lot, was going to free us. You know, it was not going to free humanity, it was not going to free black women and men in particular.

And so, She, she criticized Beyonce for that. Now, she also said a lot of positive things about Lemonade, but I feel like that got overlooked because of her critique. I should point out, and I say in the book, That bell hooks referred to this Beyonce and lemonade as Beyonce, the character.

So she wasn't going after like Beyonce, the human being, but the character in lemonade. And then her other critique was of Beyonce was on , a time magazine cover. You know, the title was that she was, one of the most powerful or influential women in the world, but bell hooks didn't like the cover, because Beyonce's on the cover kind of looking like doe eyed, or eyes glazed over, emotionless, and she's kind of like, you know, Either wearing, it's hard to tell, but a bikini or underwear, it's been described as both.

And she did not think that that was like, An image of a powerful woman and so at that time, she said that she felt that young girls were really being assaulted by images. She thought were problematic and she used the word terrorist when describing Beyonce, like saying these sorts of images are terrorizing young girls and she never lived that down.

Now I have to say in bell hooks is defense. She used the word terrorist a lot, not the way that you and I would use the word

When she was talking about, you know, say being in a dysfunctional relationship with the man, you know, she would describe like certain men as intimate terrorists. She had a scholarly approach to that word that I don't think translated, you know, to the general public, so maybe she could have done some code switching there, and I think she might have avoided some of that, that backlash.

But yeah, she wasn't afraid to go there. I talk about her critique of Beyonce, but she had criticized You know, Spike Lee and Malcolm X, which in the 90s was a huge film. She criticized, like, family films, like Home Alone. She criticized Emma Watson's role in Harry Potter.

And she was friends with Emma Watson. And so I really do think she, she did critique and love. She actually said that. If there was something she really hated or really disliked she actually wouldn't critique something. So she had to like it to a certain extent. To be willing to critique it. And so I hope that provides more context, but I understand that, you know, die hard Beyonce fans may not have forgiven her yet.

And I am a, I listened to Beyonce multiple times a week. Her critique of Beyonce is not necessarily my critique, but I did want to add additional context.

[00:21:45] Risa: It made me so sad in your book to think.

Haunted bell hooks or that somehow that she was sad about that toward the end of her life and also the idea that she was afraid of, of dying alone of being another one of these great black women philosopher thinkers who died too early and who died without hearing how important they were. Is that something that you thought about when writing the book?

[00:22:12] Nadra: Yeah, I mean I thought that was sad as well I quote one of her friends, I'm saying that. You know, this was one of the reasons bell hooks died of a broken heart was this Beyonce backlash. So it is, it is very sad to know that now she didn't die alone. She died surrounded by, you know, friends and loved ones.

She had a community of people around her. But I think. I mean, you know, she was a single woman. And so I think in the pandemic, she, she died in late 2021. And so many people, especially she had health problems. She died of kidney failure. Of course, you know, a lot of people, especially with health conditions, spend a lot of time alone to avoid getting COVID, but, you know, on the last week of her life, many people were there.

Some people were singing Buddhist chants. Some people were singing you know, Christian spirituals and gospel songs. So she was, she was surrounded by a community. But I think your point stands. I mean, she was afraid of having her works excavated is the word that her friend used. And just kind of being forgotten about like having her ideas being used by other people or exploited, but having she herself, you know, just forgotten about but one of the things she did in life to prevent that from happening is she created the bell hooks center at Berea college in her native Kentucky so that's one way that she's remembered.

I think she wrote so much that she is not going to be forgotten . She wrote, three dozen books and she's touched so many people. I think the other reason she remains really popular is because of her book all about love, which before she died, she wrote it in 2000 or it was published in 2000. But it continues to be one of her best selling books, and it appeared on the New York Times bestseller list the year that she died.

And I think that book, you see people from all, like, ages, all backgrounds, different professions, you know, models, writers, poets, filmmakers. Like, I talk about how Sofia Coppola said that book was a huge influence on her. People you wouldn't think about are huge fans of that all about love book. I think she, she had such range. And I think that is going to make her relevant for years to come.

[00:24:49] Risa: you talk more about what she teaches us about love?

[00:24:54] Nadra: Yes. So what she teaches us about love, but one major thing is that. You know, love is not a feeling. Love is an action. Just how she believes spirituality, right? You, you had to work to, you know, for your own personal liberation and to liberate other people. She believed that love was essentially someone working towards their own spiritual growth.

Or another person's spiritual growth, and she got that concept from M. Scott Peck, who wrote The Road Less Traveled in the 1970s. That's how he defined love, and when she saw that, that definition of love really resonated with her. She believed that there was too much emphasis on romantic love.

She also really challenged parent child relationships as well. You know, she didn't believe that her father loved her and I should say we haven't mentioned it yet, but I met bell hooks once. So when I was a teenager bell hooks came to my school and I met her and I remember this is 1 of the things that she talked about.

Is that not feeling that her father loved her. She also wrote about it and her books and essays. But I think that's really taboo, right? To say, you know, my parent, they don't love me. She, she was willing to go there and she was willing to get people to really think about it.

Did your parents actually love you? They may have cared for you in certain ways, but does it really fit, the definition of love being someone who prioritized your spiritual growth? Is that what your parents did for you? And she also talks about friends as well and the importance of friendships and chosen family and how she had grown up to put romantic relationships above friendships.

And she ended up in an abusive relationship for years. And one of the reasons she said she found it hard to leave is because. She didn't really have any friends anymore because she had valued her romantic relationship over her friendships and it made it that much harder to leave.

And after she got out of that relationship, she never did that again. And that was that's one of the things she talks about and all about love is that while love may take different forms, depending on if it's like parent, child, romantic partner or friendship, it's all equal. It doesn't become less, because it's a friend instead of a partner, for example.

So I think. That's one of the reasons the book resonated. I know the novelist Emily St. John Mandel, who wrote Station Eleven, said that that book made her think differently about friendships. So I think that's also, you know, really radical. We don't think about okay, my husband and my friends, should be equal in my life.

I think for many people that that was a radical concept. I think she was ahead of the curve, being willing to go there over 20 years ago.

[00:28:11] Risa: You know, I I'm, I'm struggling, I can feel so enraged the way the world is right now. You know, like I can feel like I want to be Beyonce with the baseball bat, like so many, you know, so many things make me so angry.

And I connected so much with philosophies of nonviolence when I was a kid, like that just made everything make sense to me. I was not really a Christian anymore, but like, Those people who really put nonviolence at the heart of their work. I was like, okay, I understand everything like this is everything makes sense.

If people are saying that this is what we have to do it, but it's so hard to keep coming back to when you feel so angry at the injustice of the world. But how does centering a definition of love that is. Helping another person achieve their spiritual growth or spiritual vision. How does that get us there?

Do you know what I mean? Like, how does that help save the world? Like, how does, how does a version of love that is helping us have spiritual growth become the type of love that, that helps us when the world is monstrously unjust?

[00:29:25] Nadra: Yeah. I think I mean, and that's a hard question, but I think, you know, as a Buddhist and one of the goals maybe the major goal of Buddhism is, is to liberate oneself right to reach enlightenment. If we have more people, you know, reaching enlightenment or really trying to work as hard as possible to get there. Whether that's through, prayer and meditation reflecting and pondering life. Hopefully we have fewer people acting out in unjust ways. I think that's one of the ways I think spiritual growth can help people, it can hopefully counteract how many people are hurting and acting out in ways that are either self destructive or destructive to other people or to our environment, society as a whole.

I think it also gives people hope, like you mentioned , bell hooks. was a professor at an Ivy League institution, and she was so shocked that so many of her students, who she thought, you know, they were young and beautiful and gifted, and so many of them were in pain.

They come to her office and she'd find out how depressed and hopeless some of these students felt. And I think she shared her spiritual faith with them to give those students hope, to help them think about the ancestors or the universe or, you know, just something outside of our immediate circumstances.

She thought that that was a way to give people hope. She struggled with depression and suicidal ideation, but she still turned to Buddhism. And Christianity she had different Buddha statues and other religious figures in her home as a way to help her believe that there was something else that there was something bigger.

She believed her great aunt and not just her, I guess the community believe this great aunt had a lot of spiritual power and that through that spiritual power, that they could kind of transcend white supremacy. They could transcend injustice. There was a way to tap into something greater than patriarchy, white supremacy, capitalism. That by tapping into our spiritual gifts, that was a way to overcome . And nature, too. She talks about her grandmother and other relatives.

Gardening and growing food and being self sufficient and, and that white supremacy may have kept, black people down in different ways, but they could not fully dominate nature. That was one thing, where all humanity was kind of equal. So her seeing relatives. you know, who could grow food, who could sustain themselves without buying things, for example, that that, that was a way to do that.

So hopefully I answered your question, but...

[00:32:31] Risa: Oh, I mean, yes. And also, so many more good things to think about with a writer like that. Every, everything you say, I'm like, I have 17 more questions. Which direction do I go? I want to hear you talk about her alters, the way she thought about and wrote about alters.

[00:32:47] Nadra: Yeah, she wrote this book and I don't think it's a very well read book, but it's called homegrown the book is a conversation between her and this Mexican American artist named Amalia Mesa Baines, and they talk about alters. That altars were a form of resistance, right?

That both you know, the indigenous people of the Americas and black people were colonized and that includes by religion and told that their ancestral practices were wrong. Altars were a way To practice those spiritual traditions that honor the ancestors and people could have altars and she also talks about yard shrines in ways that their white oppressors maybe didn't recognize. Especially in West African spirituality, whether you say ancestor worship, or just honoring the ancestors is a huge part of West African spirituality. And African Americans didn't lose that.

They continue to do that by, she talks about placing stones in certain ways that a slave holder wouldn't have understood . She talks about going into people's homes, and this is true of some of my family members as well, and having all these photos of different ancestors arranged usually in like a central part of the house also a way of kind of having an altar maybe not an altar where you have candles and herbs and things like that, but it was still a way to kind of pay tribute to the ancestors and to help kind of people across different generations know who their ancestors were, who their, you know, great great grandparents or aunts and uncles were.

And so she believed that was a form of resistance that both black people. And Latinx people engaged in and she talks about this artist that I had the opportunity to interview a couple of years ago, Betty Saar, who does a lot of work with alters and with kind of ways of, of honoring elders and ancestors . It's another way also to think about how, like, the ties with Africa were not fully severed, you know, or weren't really severed at all in some ways.

She talks about to the altar of sacrifice. So she's in that way. She's kind of talking about like the Buddhist right who sets themselves on fire for a social cause and she believes whether you know it was Buddhist monks and nuns who were doing that or people like Martin Luther King and Malcolm X who were assassinated for what they believed in.

So that's another way the altar of sacrifice.

[00:35:31] Risa: How do you feel like spending so much time with these incredible thinkers and trying to piece out what really their, their spiritual vision was? How do you feel like that's affected your own spiritual vision?

[00:35:45] Nadra: Yeah, I mean, I think I really take to heart some of bell hooks is advice. She talks about in this one book it's called sisters of the game that I say a little bit, you know, doing things like paying attention to one's dreams. This is sisters of the game she's really speaking to black women in particular some of her books are more broad she's speaking to everyone, but that book is written with black women in mind and she talks about the importance of that.

So I've been trying to pay more attention to my dreams, for example I'm consciously remembering them telling my husband what I dreamt about and like even trying to work on analyzing them . When she was a child her grandmother would analyze her dreams.

So that's one thing. Bell hooked, I was trying to honor her and she was really on my mind.

Obviously the whole time, but I think in a way she talks about remembering as a way of someone who's departed the earth, keeping them alive. And I, there were times I was so deeply embedded in her work, not just reading her books. My book pretty much cites, there's about 10 books that my book analyzes of bell hooks, but I also was listening to like radio interviews and watching YouTube videos.

And so she really felt alive to me. Like I had to remind myself she had actually passed away. In some ways her, her spirit just felt very alive when I was writing the book. And the one thing that I was really touched by. Is that so there are five people who endorsed the book and three of those people actually knew bell hooks like really like one was there singing when I mentioned people singing gospel songs to her, one of them who endorsed it was one of those people.

And so it made me feel like, you know, those three people doing it was short of like having bell hooks herself kind of, you know, endorse this book. There's so much to learn from her in terms of her critiques of capitalism, I'm not a Buddhist, but I also think like writing the book has made me more interested in Buddhism.

[00:37:59] Risa: Yeah, she's so ahead of her time, too, in insisting on looking at the interconnectedness of oppression, you know, I think we get that phrase from her, like, imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist patriarchy, like, let's acknowledge how all of these things form a web of oppression that pushes on us in So many layered ways that just pulling out one aspect of that can mean that we miss some of the complexities of oppression.

I, that's something I'm really thankful to her for because we need to be able to see it in all its dimensions, I think, to talk about it.

[00:38:39] Nadra: Yes, yes. And thinking about that term and also terms like intersectionality so I'm an education reporter. That's my 9 to 5 job, but bell hooks, her books, Kimberlé Crenshaw's books, they've been targets of book bands in Florida and other places. And so, you know, imperialist, white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy, you know, that phrase itself is apparently, you know, a threat that people want, you know, to wipe out or don't want young people to know about it.

This year that's been kind of disturbing to know that her works have been targeted in that way.

[00:39:19] Risa: Yeah. Yeah. It's, it's sort of such a strange tension between like the joy at her being on the top of the New York Times list 20 years after writing that book. And also, you know, the, the, the more, the more we celebrate how important and visionary she was, the more that fascists are motivated to try to make sure we don't have access to her,

[00:39:42] Nadra: Yeah, yeah. And again, this is something she also predicted, really. She talked about that in Homegrown, which I think was published in 2006. She talked about book banning and affirmative action and like all these things that we've seen this year. She, she was concerned about them so long ago.

[00:40:02] Risa: She knew.

What do you think, what do you think she would want us to walk away with today? Like, not armed with, because the language of violence isn't quite correct in this case, but what do you think she would want us to walk away with rooted in or lifted up by?

[00:40:22] Nadra: I think. The idea that we can create our own spirituality. I think there are so many people who are doing this now, but I think there's still people who are kind of, you know, afraid to practice syncretism in some way. So whether that's like, Hey, I'm a Christian, but I'm also gonna honor my ancestral practices.

There's still a lot of fear around people, you know, doing that. But I think she would want people to feel that they can practice their spirituality in whatever way Most benefited them and in whatever way they felt heal them because I think her writing her spirituality, it was essentially about healing.

And so when she talks about a liberatory, you spirituality or love as liberation, I think healing it's her goal. Whatever heals you is the faith path you should follow.

[00:41:29] Risa: I love that. And I'm going to keep to, and, and be loud about the idea that like, To love something is also to tell the truth about what isn't right in it. To have a version of a religion that doesn't let you ask questions about it, that only wants to take 10 percent of your income every year and build a megachurch, I, you know, that's not the, kind of faith that I think is coming to save us.

I want that knowledge from her to be writ loud.

[00:42:01] Nadra: Yes. Yes.

[00:42:03] Risa: You know I don't want to let you go without talking about children, centering child liberation. Can you, can you talk about that a little bit?

[00:42:12] Nadra: Yeah. I mean, I think that she, she really felt that a, that Jesus or other religious figures, but especially she's talking about Jesus because that's when she was a child. She was exposed to you know, saw the value and little children, but I think. When she was growing up, she felt that she had no rights and on top of that is a black child as a girl child.

She really had no rights. And she wanted children to feel that they were loved that they had value. And she had some adults in her life who were all different in some ways, kind of outcast in some ways, who did value her and who did encourage her in ways that her nuclear family in which she was the scapegoat, did not.

And she tried to be that sort of person for other children. She believed that adults whenever you were around a child, you should try to find some way to affirm them to affirm their talents, beauty, et cetera. And so when she went to my school, there was someone I was friends with. after she met Bell Hooks, she was like, Bell Hooks said that I was beautiful and that I should have my hair natural and at the time she was chemically straightening her hair. And so she, she listened to bell hooks. She stopped straightening her hair and she was so excited and she went around like telling all of us. Bell Hooks said I was beautiful and I mentioned that in the book.

Just to just share, hey, from what I know, she really did practice what she preached in terms of, affirming children and especially black children. She wrote books for black children to try to Affirm them, before white supremacy or colonization made them feel bad about themselves.

She really believed in the value of the extended family because she felt like that child would have access to more people who might affirm them in ways that maybe their parents did not . Maybe they were unloving.

Maybe the father was a patriarch in the way that her father was. She wanted more people around, you know, the village to raise the child. She was really influenced by Toni Morrison's The Bluest Eye, which came out when she was a teenager, and that book is about a black child whose worth is questioned because she's dark skinned, and she's poor, and her own family does not see the value in her, and so I think, uplifting children seeing their divinity was another way that she was radical.

[00:45:05] Risa: Such a good way to remember the, the radical power that each of us has in the world is to stop thinking about it abstractly and just think about how one thing you say to a small kid can spin their whole lives in a direction, you know?

[00:45:21] Nadra: And child liberation theology, the people who believe in that Or arguing, look, Jesus was a child. He, he experienced childhood and he was divine as a child, just like he was divine as an adult. And so we need to look at children as, as being divine,

they don't have to reach adulthood, to be valuable humans. Bell hooks was very. anti corporal punishment. As well, and so when she was talking about children's rights, I don't know how much she knew she influenced that movement. But some of the pastors and other religious people involved in that movement, they directly cite her. She wasn't a mother herself, but she really valued children.

[00:46:10] Risa: I think it's important given so many current political contexts to also highlight that children aren't property either.

[00:46:18] Nadra: Yes, yes.

[00:46:19] Risa: parents don't get to determine their identities.

[00:46:22] Nadra: Yeah, and I think there's that's also like a part of her capitalist critique as well. In a capitalist society we learn to look at children as our property, and when you start to unpack capitalism, you start to see that children are not something you own. They are not objects . She believed that fathers played a huge role.

And could play a huge role in making those families functional by child rearing, by taking care, by being equal, parents. she Felt taking care of children, caregiving teaches men important lessons.

And so, she wanted men to be very involved in, in raising their children.

[00:47:05] Risa: Just makes sense, right?

[00:47:07] Nadra: Yes.

[00:47:09] Risa: Do you think we could finish with, would you read us a bit or talk to us a bit about her witch poem?

[00:47:16] Nadra: Oh, sure, sure. So, in addition to everything else, she was also a poet and she has a book called Appalachian elegy, in this book, she talks about the way that she and her friends try to honor the legacy of her mother, her recently departed mother, Rosa Bell.

Hooks did not publicly identify as a neo pagan, but her writings suggest that she too was influenced by both that movement and possibly by spiritualism. In the Introduction to Appalachian Elegy, her 2012 book of poems, Hooks discusses partaking in a ritual to commune with her late mother's spirit in the Kentucky hills.

In the Buddhist tradition, she started the ritual by chanting, but then she and a group of eco feminist friends Quote, called forth the ancestors, spread sage, planted trees and dug holes for blossoming rose bushes in the name of our mother, Rosabelle. Hooks and her eco feminist friends operate very much like a coven, an argument strengthened by a poem in Appalachian Elegy that honors the witch, the women with the quote, wilderness within.

In the poem, The Wild Woman is an aging crone, wise hag, who not only holds mystery, but can stir the cauldron, tin the flames, and carry messages from the future. This crone sounds very much like Hook's maternal grandmother, Saru, a woman more comfortable outdoors than indoors, and who prophesied by interpreting dreams.

But the poem may also be an ode to the witch generally. For Hook's view, the Salem Witch Trials is, quote, an extreme expression of patriarchal society's persecution of women and a message to all women that unless they remain within passive subordinate roles, they would be punished, even put to death, end quote.

I mean, I like that poem so much and that it could possibly be about her grandmother, the witch generally, and that yeah, that Hooks, was moved to comment on the Salem witch trials and what they signified about women then, and even today, what happens when women, you know, get out of line, quote unquote.

[00:49:41] Risa: Such a powerful way for us all to remember that one, that that message has been there for so long, so loud that if we step out of line, we'll be punished. But also that like those, those wild ants, those, those women who were more comfortable outside, you know, those women who talked to their distant mothers, that they've been there too for a long time.

And that even these like icons of a feminism that can seem very militant and anti spiritual sometimes that they had at their heart a knowledge of those grandmothers and a respect for a non violent Christianity and a liberatory radical Buddhism, you know, that those, those strains were there and that they want us to have them too as we continue that work.

So thank you so much for your work and your incredible research.

[00:50:41] Nadra: Oh, thank you.

[00:50:42] Risa: Yeah. I, I, I, I love reading your, your books because it's like Nadra, read all the fucking things. nadra, iss not Googling,

[00:50:53] Nadra: Thank you.

[00:50:56] Risa: Nadra. Read all the books.

[00:50:59] Nadra: Yes, I appreciate it. And I hope you feel better, by the way.

[00:51:04] Risa: Oh yeah. Thanks. I'm fine. My, my kids, you know, at that age where she gets everything, so we get everything. So we're fine. We're fine. It's all fine. Just carry on. Right.

[00:51:16] Nadra: Yes, yes.

[00:51:17] Risa: yeah, thanks so much for your time today. I know writing about the, the spiritual visions of people takes an enormous amount of reading and work and doesn't make us rich. So I hope that you know that that work, is incredibly transformative that rescuing and tracing together and weaving together those insights and making sure that that part of that thinker's story is told, it's like she said, like someone told her that she had the God voice, you're like carrying through that God voice in her. And that I think is, is transformative work. So I hope that you know, we appreciate you. And thanks for coming on the podcast again. And blessed fucking be.

[00:52:03] Nadra: Yes. And thank you so much for having me.