Lydia Cabrera was a white Cuban writer and ethnographer who crossed boundaries — of gender, nation, and spirit. She loved women. She recorded the voices and rhythms of Afro-Cuban priest-artists, working to honour sacred traditions that were never hers. In this episode, we sit at the threshold of her work, asking what it means to document and to testify. We follow Cabrera from her queer loves in Europe to her home in Havana — a sanctuary of magic and scholarship shared with María Teresa de Rojas — and then into exile in Miami, where her archive became an altar of memory and care.

We listen for the echoes in her recordings with Josefina Tarafa — the only ones she ever made — and reflect on how well-meaning magic can veer into victim-blaming. Together, we root ourselves in reality: illness, loss, and the world that still breathes beneath it all.

This is a story about queer domesticity as revolution, about the dangers and power of metaphor, and about the witches, archivists, and healers who keep testifying — for the living and the dead.

Lydia Cabrera: Admit to the Reality of the Unreal

Begin by greeting the monte.

The wild thickets. The tangle of plants and stones and spirits. The monte isn’t backdrop. It isn’t scenery. It’s a being, a chorus, a field of kin, a veined and leafy living place of memory, urgent and present and outside of time, a promise of possibility beyond the built and colonizing and traumatized world, a place for imagining and incarnating power when the systems, discourses, layers of culture try to tell you, you are powerless.

You are not fucking powerless.

You are alive with power. You are a living lineage of life like a sacred thicket, flickering, raging, persisting.

Today we follow the life and work of Lydia Cabrera, who turned her ear to that chorus, who over 70 years ago cracked the dominant world view of her race and class to glimpse beyond, queered anthropology, preserved a web of voices singing, passed an oral culture and knowledge on into the future, and built a lifetime of listening.

Lydia listened to people her peers dismissed, and from their songs, proverbs, and secrets she shaped books that were unlike anything else in the world at that time, books that read like grimoires — preserving magical knowledge and creating the archive that, generations later, is still an essential touchstone for Lucumí, Santería, and Palo Monte.

Lydia Cabrera was born in Havana at the turn of the 20th century, May 20, 1899, into privilege, into whiteness, into the colonial elite. She studied art in Paris, immersed in the surrealists, trained her eye on paintings. But then she returned to Cuba, with her love María Teresa de Rojas at her side. Together they began listening - to the archives, to the architecture, and crucially to the stories, proverbs, songs, and plant wisdom of Afro-Cuban neighbours and elders.

Lydia began to write:

“Cabrera’s ethnographies of Afro-Cuban religious life are the heart of her later work. These include research on the Yoruba in Cuba published as Yemayá y Ochún (1974), an account of the verbal arts surrounding the goddesses of the seas, sweet water, and love; Koeko iyawe (1980), concerning the structure of the Afro-Yoruba religion, its rituals, sacrifices, and cures; Anagó ([1957] 1986), a lexicon of creolized speech in Cuba; Otán iyebiyé (1970), on the beliefs of the priests of the orishas about precious stones; La laguna sagrada de San Joaquín ([1973] 1993), about the rituals of the followers of Iyalosha, the water goddess; and La medicina popular de Cuba (1984), a study of folk medicine among Afro-Cubans.

The seminal work on the Efik and Ejagham male “leopard society” (Ngbe) in Cuba is represented by La sociedad secreta Abakuá (1959), an account of the myths, rituals, ideography, and organization of the Abakuá religion and their influence on Cuban religious life; Anaforuana (1975), offers an ideography of initiation, funeral leave-taking, and membership in the Abakuá society. Cabrera’s research on a creole Kongo society in Cuba appears in La Regla Kimbisa del Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje ([1977] 1986), a close look at a nineteenth-century creolized Kongo-Catholic religious group and its leaders; and Reglas de Congo ([1979] 1986) examines the creolized Kongo-Angolan ritual, religion, ideography, and folklore of Cuba.”

and above all, El Monte—a book of plants and places, remedies and spirits, where the sacred forest itself is the protagonist, the hero, the heroine… or actually those metaphors don’t work do they? Because the Monte is multiple, medicine and poison, the source of curses and divinities and stories and blessings and songs, a living limitless archive of whats possible.

“El Monte lists more than five hundred herbs, the ailments that they are alleged to cure, the spirits that preside over their healing powers, and the creolized Yoruba, Ki-Kongo, and Ejagham (Abakuá) words that name the leaves in Afro-Cuban terms.

In addition, we find whole legends associated with certain leaves: miniature narrations. “Truths that can be rendered in a dissociated moment,” Susan Sontag points out, “however significant or decisive, have a very narrow relation to the needs of understanding. Only that which narrates can make us understand.” (1977, 230 And in fact, El Monte is a miracle of narration, brought into being by a woman who uniquely combined the powers of a painter, an interior designer, a sculptor (...) a writer, a linguist, and a passionate student of the folkways of Black people.”

She followed the folkways even when she couldn’t go home.

Cabrera died in Miami exile in 1991, her vast archive of field notes, recordings, secret symbols and whispered cures and correspondences now housed at the University of Miami, and the archive spills and vines out of that temperature-controlled indexed embrace. It lives wherever plants and spirits are treated as kin.

Do you know where the archives are that keep your people, the story of your community, your foundations? Who is quietly keeping the notes, the flyers, the stories? Could you be their accomplice? And can you hold the white boxes in your mind and then see the trees beyond? Keep the thickets, thick forests, places that have felt alive an unmanaged, untouched to the front of your mind and lets bring them as an offering to Lydia’s story, sacred storyteller trickster archivist. Ask permission to listen.

Cabrera’s work is slippery on purpose. She refused neat categories. Not fiction. Not science. Not exactly folklore. Her stories destabilize the colonial gaze.

Her method was intimacy. Long conversations. Shared meals. Sitting on porches and listening for hours. She blurred the line between observer and participant, between art and ethnography, and in doing so she invited us to blur our own lines too.

But this comes with tension. Lydia studied closed practices and shared them.

“At first Omitomí feigned total ignorance of the Afro-Cuban world of worship: “I don’t know nothing. I was brought up with white folk.” Gradually it developed—and her name was a strong hint of this—that Omitomí was one of the most respected Afro-Cuban religious authorities in all of Cuba, and she introduced Cabrera to her friend Oddedei (Yoruba: the hunter has made us this). The two of them, Omitomí and Oddedei, saw to it that Cabrera traveled to Matanzas. This city, “the Ile-Ife of Cuba,” was reputed to be home to the true spiritual overlords of the Afro-Cuban religion. The priests and priestesses there, many in their eighties and nineties, were deeply erudite and spoke the three major creolized African languages of Cuba. Oddedei made Cabrera swear that “no one was to touch her head” (i.e., no one was to initiate her into the Lucumí or Kongo religion, “so that you can write freely about our traditions, for once a iyawo—a bride of the gods, an initiate—you will never be allowed to speak”).

And so a pact was sealed and word spread that Cabrera was a white person of distinction who truly respected Black culture and who was quite generous with her informants as regards gifts, services, and favors. As her network of informants grew in the 1940s and 1950s, she found that her house, the Quinta San José, was admirably sited, built as it was in Pogolotti, a barrio of Marianao, a western suburb of Havana. For Pogolotti is famed to this day for its African-influenced religious activities. It is the site of one of the most prestigious and culturally important Abakuá lodges. Cabrera comments: “In fact Pogolotti was a barrio entirely enlivened with Black people and culture. There were Abakuá, there were paleros, there were Yoruba diviners (babalaos), excellent people, no? I had but to cross the street to be in Africa.”

These texts preserve knowledge and cross the street.

Who needs you to listen, to keep faith, to keep secrets? Who needs you to show up, cross the street, testify, amplify? This LIbra season feel the weight of your contradictions, hold them in your hands and sway with the balancing. Feel the wave of power that comes from holding and owning your fractured selves and complex truths. You are the bend in the binary, the center of the Venn diagram, you are Magic.

In 1954, Cabrera published El Monte. People call it the Bible of Afro-Cuban religions, but it isn’t a text of rules or dogma. It is a pantheon of forest spirits rendered in ink.

Here, ceiba trees tower as holy columns. Rivers speak. Plants reveal their cures but also their demands. Remedies are never just recipes—they’re relationships.

El Monte teaches us to perceive the sacred as ecological, specific, and local. The monte is not metaphor. It is presence. And its not pure, not just old growth, not out of reach. El Monte is everywhere.

"Wherever you see a little bit of grass, that’s where you can find a remedy"

In El Monte, Lydia writes, quoting one of her teachers, Catalino:

“”Wherever you see a little bit of grass, that’s where you can find a remedy”

For the health of his body and soul, every Black person will resort to el monte. ‘It’s an instinct,’ says Catalino. ‘We’re herbalists. We’re pulled to el monte!’

But the reader should not think that this word Monte, or bush—here, we never say “forest”—is only used to designate an expanse of uncultivated land populated by trees. In Havana, any empty field covered in plants is considered a “monte”—or even a savanna! (Just as an aguacate [avocado] or laurel tree is called a plant!) An uncultivated parcel of land in a solar of the most meager proportions is categorized as a manigua (wilderness, bush) by virtue of wild plants sprouting in it, and it will be referred to simply as a “monte” or “manigua.” Every space where leaves grow dense is suitable for depositing an ebo, the usual “offering” in the Regla de Ocha intended for a Santo that is “not from the water.” (Offerings for those that personify the river or ocean, like Oshun and Yemaya, are generally taken to the bank of the river or the seashore.) That way, Black people living in the capital do not need to walk very far to find a “monte.”

The majority of plants that are used constantly—for bathing and cleansing oneself of bad influences, washing the floor of a home, burning as incense, or simple homemade remedies—abound in these miniature montes, which are so accessible and no less worthy of respect.

It is precisely the most common plants that have the most prophylactic value; they are the most indispensable for what we might call their daily, preventive magic. They protect us throughout our whole lives, which are constantly threatened by exceedingly subtle dangers.”

Lydia wrote in a time where the people felt constantly threatened by exceedingly subtle dangers.

At the turn of the century, Havana was a city of contradictions: sugar wealth and poverty, colonial legacies and radical ferment, hurricanes that could wipe away entire barrios, and a nightlife that boomed under prohibition in the United States as pretend pious rich Americans made laws and then left town to get wasted. The rhythms of rumba and son spilled into the streets; the scent of tobacco and sea salt hung in the air. Lydia studied in Paris but fled back home to Cuba in 1938 to escape the Nazis who were coming like a wave of bile and puss and blood, drunk on cruelty, flailing under the rot of the narrowing of mind and self that comes from focusing on blaming Others and pretending you are superior while inside you know you are just another flawed and broken being longing to be with the whole that you pretend to despise.

If you too find yourself in a time and place of exceedingly subtle dangers, listen like Lydia. Take up the task of stitching yourself into the world of the other, step by step, language, teacakes, music, shoulder to shoulder.

Learn three plant names in more than one tongue. In English, Spanish, in the Indigenous languages of the land you are on, in the language your neighbours speak. Greet your neighbours by name, ask a more intimate question, offer a crack in the social mask, let their rhythm, their pauses, their laugh, their struggle, their heartbreak root in you. Commit small spells of anti-erasure.

Commit small spells of anti-erasure.

Early in her career, Cabrera published Cuentos negros de Cuba. Afro-Cuban folktales gathered and retold: animals that talk, orishas who scheme, tricksters who bend power back on itself.

These stories aren’t quaint. They’re survival technologies. They carry laughter, subversion, and continuity. They kept Black Cuban cosmologies alive and wove them into a pantheon that slavery couldn’t sever.

Lydia grew up in a home full of art and intellectuals, and people working to free their country from dictatorship, but still her vision and language don’t quite escape the colonial, racist, discourse that soaked the streets and coloured the air.

Still her attention and lifelong dedication to valuing, honouring, preserving Black knowledge and philosophy and culture was completely radical. And part of what powered that radical openness was that Lydia’s perspective was queer.

The first major love affair we get hints of in the introduction to El Monte. Quote,

“Lydia had met Teresa de la Parra in Havana in 1924. Their friendship was rekindled in Paris in 1927, and it lasted until Parra’s death in Madrid in 1936.”

That’s the extent of the mention in the body of the text. But the footnote reads: “Cabrera and Parra had an intense relationship that lasted nine years, (1927-36) During those years, Cabrera was between twenty-seven and thirty-five years of age, while Parra was between thirty-eight and forty-six. The impact of Parra’s untimely death is not discussed in detail here, presumably to avoid dwelling on a very intimate and painful subject.”

This love between one of Venezuela’s best-known novelists and Cuba’s most important urban ethnographer feels like it probably wouldn’t have been too intimate to make part of the story if it wasn’t a queer story, a lesbian story, a story about women who defied machismo culture to create and describe worlds beyond.

Before Parra’s death, before Cabrera returned to Havana to begin the deep listening that would shape her life, she was inside a queer love story marked by illness. Parra’s tuberculosis set the tempo. Where they travelled. How they spent their days. It must have pressed on their nights.

Later, Susan Sontag would write that tuberculosis — and later cancer — are never just diseases. They become metaphors. Romanticised. Blamed. Shrouded in shame. The person disappears behind the idea of the illness. The beloved dissolves into symbol.

And this is still happening. When my neighbour was diagnosed with cancer, the first thing her well-meaning spiritual friends asked was: What haven’t you processed? What are you repressing? This is the cruel, biting end of all that manifesting talk. The ugly truth behind The Secret. It’s victim-blaming bullshit, it’s bad magic.

Witches, we need to root into the painful deep reality that our bodies exist in systems that make us stressed, sell us poison, fill the air with microplastics, and sometimes we get sick. And eventually we all die. That’s not a failure of will. That’s the ground beneath our feet. That’s the world we live in.

And Lydia Cabrera knew something about living with what the world prefers to repress. She once dedicated her work to Maria Theresa de Rojas with the phrase “Those who deem themselves intelligent find that admitting to the reality of the unreal is detrimental to their prestige.”

And if you’ve lived inside illness — as Parra did, as Sontag did, she wrote Illness as Metaphor while going through breast cancer treatment — you can start to see what was hidden before. You can get glimpses of the scaffolding of ableism. The way doorways, sidewalks, conversations, even intimacies are built for a fantasy of health. Compulsory vitality. And just like the heteronormative, white, imperialist construction of “normal,” this too masks the lives lived at the edge. “the reality of the unreal.” Unreal to whom? The reality of queer love hidden in plain sight. The reality of illness reduced to metaphor.

Cabrera’s El Monte doesn’t give us the Hallmark version of magic. It’s not all light and white dresses. It’s also fear and hexes and survival in a dangerous, unequal world. You can feel the pulse of resistance in it, yes — spells that protect against the plantation owners, charms that call down justice. But you also see the way magical thinking might be sharpened by desperation, by paranoia, by the endless violence of colonialism.

And I think that’s still a risk for us. Witches, we know magic can be a weapon, a shield, a balm. But it can also slip into what our friend, grief worker, diviner Zoe Flowers calls spiritual psychosis — a way of dissociating from reality, drowning in superstition or conspiracies, instead of meeting the hard, holy work of life and justice and peacemaking.

The lesson isn’t to abandon the magical. It’s to remember that magic is always bound up with the world we live in. It can rot or it can nourish. It can isolate or it can connect. Every curse, every charm in El Monte testifies to that tension.

And for us, the call is to keep turning back toward reality, toward each other. To make every moment — even the painful, even the mundane — into an altar.

In Havana, Cabrera would find herself living in another threshold. With María Teresa de Rojas, she restored a home. Across the street, El Monte stretched its tangled roots and branches through a neighbourhood alive in Afro-Cuban spirits, stories, medicines, resistance. Inside their walls: queer domesticity, care as revolution, a sanctuary for two women who chose each other.

Queer love, illness, El Monte — all of these demand that we learn to see what is right here, but hidden by the stories power prefers to tell. Cabrera and de Rojas remind us: resistance is not only in the forest, but also in the kitchen, the bedroom, the garden.

For Lydia and María Teresa, their home became an extension of their care, a site of restoration, a sanctuary for their shared work.

“Lydia and Titina attacked the work of reconstruction and decoration enthusiastically. They replaced destroyed doors with others salvaged from mansions being demolished in Havana. They repaired the roofof the lean-to in the garden with antique wood. The coffered ceiling from the Santo DOmingo convent, which would later become the headquarters of the University of Havana, was saved from demolition and installed in the tower. They repaired the original iron gates and fences , and they installed others from the ancient Havana jail. They decorated the hallways with colonial era tiles (...) Finally, they furnished La Quinta with carefully chosen items. Despite being a true museum of antiquities and craftwork, photographs show an inviting creole interior, as well as a marvelous informal courtyard.”

Queer domesticity is world-making. It is altar and shelter and salvage, revolution and everyday tenderness.

Queer domesticity is world-making.

One of Cabrera’s most daring moves was to write about the Abakuá secret society — a brotherhood with roots in the Ekpe “leopard societies” of the Cross River basin in West Africa. In Cuba, Abakuá became both feared and powerful, binding dockworkers and traders into mutual protection and secrecy.

Its ritual signs, the Anaforuana, are complex geometric figures that carry power, membership, memory. They look like crossroads, constellations, veves, sigils. Cabrera published them. She mapped them into her books.

“Cabrera’s teachers shared detailed information, thereby risking their personal safety, since initiates who shared details with outsiders about hidden rites were rejected by the group. Because government authorities repressed Abakuá in the colonial and republican periods as “criminal” or “antisocial,” Cabrera’s Abakuá teachers understood her as an ally whose publications could help educate Cubans about their institutional and spiritual legacies from Africa. In the preface to her 1959 monograph, she wrote: “The false accusations continually launched against rites imported by slaves fell fully upon the Abakuá . . . [making] the elder Saibeké and other initiates break their silence and clarify for us their Mysteries” (Cabrera 1959a, 11). Cabrera convinced her Abakuá teachers that their culture was integral to Cuban national identity and that her documentation would contribute to educating the nation about its true historical development.

(...)

Cabrera’s Abakuá phrasebook is the largest work available on any African diaspora community in the Americas, with 530 pages of transcribed terms, phrases, and chants in the Abakuá “sacred language,” with intuitive interpretations in Spanish. There are more than 6,300 entries, organized alphabetically according to the first word in the passage.”

Cabrera’s work exists within the movement called Afrocubanismo, which uplifted Black culture but often through a nationalist or exoticising lens. She preserved, but she also appropriated. She resisted erasure, but she was also entangled in structures of whiteness and power.

And then there is this:

in the 1950s, Cabrera and Josefina Tarafa lugged recording equipment into Matanzas and Havana to capture voices and rhythms that no text could hold. Música de los cultos africanos en Cuba — sacred chant, drum, invocation.

“The collection consists of 14 LP discs containing over 11 hours of audio recordings, along with liner notes and photos. Given its scope and quality, the collection is arguably the single most robust multimedia archive of Afro-Cuban musical traditions in the mid-20th century.”

The only recordings Cabrera ever made. If her books risked distorting what she was told, these recordings are something else: breath and vibration, words dissolving into rhythm, the sound of a priest’s tongue striking the air. Cabrera said she wanted to avoid “the dangerous filter of interpretation,” and here she finally did — becoming a medium for sound itself.

We inherit the songs, the conversations, her brilliance and her compromises. We can aspire to be trusted like she was, to be allies and accomplices to each other. Name our sources, cite Black Cuban scholars, and direct attention toward living practitioners who carry these traditions forward today.

Witches, in your grimoires, add a sources page. Practise citation as devotion. Record who taught you and what you want to learn. Honour the lineages.

After the revolution, Cabrera lived in Madrid, then settled in Miami. Exile cut her from her homeland but didn’t sever her work. She edited, compiled, and protected her materials. She wasn’t alone.

María Teresa de Rojas was more than Cabrera’s life partner for over five decades. She was a collaborator, historian, and always a co-conspirator in the intellectual and cultural labour of their shared life. Their Havana home — restored together stone by stone — was a hub of conversations and ideas, a sanctuary where everyday love intertwined with the preservation of Cuba’s past and the dreaming of its future. Later, in Miami, their apartment carried the same energy: a refuge that was also a workshop, a testament to their enduring partnership.

Today, their archive is a shrine: thousands of pages of notes, correspondence, photos, audio, objects. A sacred accumulation of memory, love, and relationship.

No archive is neutral.

No archive is neutral. Its always hopeful of the future and fundamentally bereft. There are always stories that exceed, ancestors we can’t find. But beyond the archive is the reality of the unreal, in the trees waving and moss weaving, I can imagine an archive of another kind. El Monte.

I dipped into these great books with reverence, sometimes with the feeling like I was trespassing.

These are closed practices. Santería, Lucumí, Palo, Regla de Ocha—traditions held and tended by communities who decide what may be spoken and what must remain within the initiated. Lydia Cabrera was permitted to record, to write, to publish. She was trusted with sacred stories, medicines, chants. But whiteness, exile, and power imbalances inevitably shaped her gaze, and distortion lingers in the record. At the threshold of this work, as the door swings open and we hear the city and the wild thicket all interpolated with each other calling us, I want to honour those who chose to share their knowledge with her. In their names, may we make good on their trust. May we rise to the challenge of documenting, archiving, and testifying with whatever small power we have, not to consume, but to protect; not to extract, but to honour.

Because testimony is not only about the past, testimony speaks truth into the white noise of distortion. Where we have power, we must testify to the present. To the Black, Latin and indigenous communities targeted by racist violence. To peaceful protestors beaten and jailed. To immigrants and citizens alike subjected to the deranged tantrums of white supremacy, here and across the globe. To honour Cabrera’s sources is also to commit ourselves to witnessing now. To refuse silence. To speak, write, and act in the service of those whose voices are suppressed.

We call:

- Calixta Morales, Oddeddei, the unforgettable.

- José de Calazán Herrera, Bangoché, Moro, the first frank collaborator.

- Teresa Muñoz, Omí-Tomí, who opened the door.

- Enriqueta Herrera, keeper of stories.

- Nino de Cárdenas, witness and voice.

- Dolores Ibáñez and Petrona Ibáñez, iyalochas, daughters of Francisquilla.

- J. S. Baró, Campo Santo Buena Noche, banganga of Pogolotti.

- Gabino Sandoval, hijo de Allágguna.

May their words echo beyond the page. May we meet their generosity with reverence and responsibility. May we testify in their name, and in the name of all who still need us to show up, speak up, and honour their experience with courage.

May our research be relationship. May our citations be offerings. May our magic keep secrets where secrets keep people safe. To the papers and to the plants. To the tellers and the listeners.Thanks.

And blessed fucking be.

Episode Notes

The music in this episode comes from Cuba - Les Danses Des Dieux by Ocora.

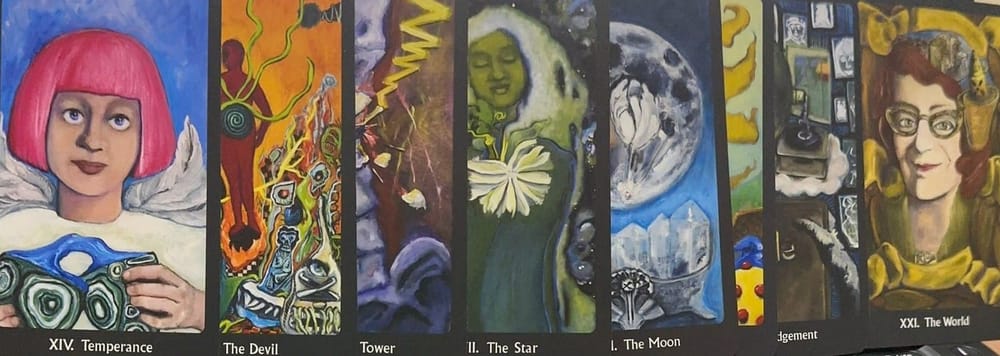

The photo is from the Cuba Heritage Foundation, via No Country Magazine.

Works Cited

Cabrera, Lydia. Anaforuana: Ritual y símbolos de la iniciación en la sociedad secreta Abakuá. Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1975.

---. Cuentos negros de Cuba. Havana: 1936.

---. El Monte. Havana: Ediciones C. R., 1954.

---. La laguna sagrada de San Joaquín. Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1973.

Cabrera, Lydia. Cabrera Papers and Records. Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami, digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/chc0339.

Cabrera, Lydia, and Josefina Tarafa. Música de los cultos africanos en Cuba. Havana: ca. 1956. (14 LPs, privately distributed). Digitized selections available via Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

Font-Navarrete, David, and Martin Tsang. “An Introduction to Música de los cultos africanos en Cuba: The Cabrera-Tarafa Collection of Afro-Cuban Music, ca. 1956.” Beyond the Archive. Manifold @ CUNY, 2023. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/beyond-the-archive/section/9171a68c-58f6-4c71-94c8-7daba4455fa1

---. The Yoruba/Dahomean Collection: Orishas Across the Ocean. Produced by the Library of Congress, 1998. (Includes selections from Cabrera/Tarafa recordings).

Marks, Morton (curator). Afro-Cuba: Music from the Lydia Cabrera Collection. Smithsonian Folkways, 2001–2003.

Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978.

---. AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1989.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Vintage, 1983.

Wirtz, Kristina. Ritual, Discourse, and Community in Cuban Santería: Speaking a Sacred World. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007.

---. Performing Afro-Cuba: Image, Voice, Spectacle in the Making of Race and History. University of Chicago Press, 2014.