Queer saints, wolf-rites, horned gods, and the sacred work of finding your pack.

Long before roses and cards, February held a pulse beneath the frost: love that moves quietly through the soil, through chosen kin and the bodies of the earth. It was the current of wolves running together, of women and men gathered in rites of initiation, of goddesses whose power nurtured grain, birth, and wilderness alike.

This is not the tidy, consumable romance of greeting cards, but a love that breathes, murmurs, and finds you in secret, in packs, in circles, in shared joy — waiting for those willing to hear its call.

Mid-February in the Mediterranean was a moment of wild rites, civic purification, and stories of forbidden love.

The feast of Lupercalia, already a collage—wolf-linked, erotic, and fiercely communal—later collided with the legends of early Christian martyrs named Valentine, whose stories of secret unions and love outside empire-sanctioned power quietly resonate with queer kinship.

Tracing these threads through Roman paganism, Christian remaking, and deeper mythic figures like Pan and the Bacchae, we can encounter a Valentine’s story that honours ecstatic connection without erasing histories of empire and suppression.

The Manufactured Romance of February 14

The modern holiday—roses, lace, hetero-normative pairing—is largely a medieval and early modern construction, layered over older rites and later commercialized.

The association between February 14 and romantic pairing doesn't appear in Roman sources. It emerges in the late fourteenth century, most famously in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Parliament of Fowls, where birds gather on Saint Valentine’s Day to choose their mates. Medieval poets helped transform a martyr’s feast into a celebration of courtly love.

What we now recognize as Valentine’s Day is not a simple survival of pagan ritual but a layered construction — Roman civic rites, Christian sanctification, and medieval literary imagination sedimented together.

Courtly love traditions in medieval Europe did much to shape what we now call Valentine’s Day, long after its supposed origins.

The Church didn't invent love in February, but it did absorb and redirect existing seasonal energies.

St. Valentine as a Queer Figure

There are multiple Valentines in the early Christian martyrologies; the historical record is fragmentary. What matters symbolically is that “Valentine” becomes associated with secret marriages, forbidden unions, and loyalty to love over empire.

Some legends suggest he married couples in defiance of Roman authority. Others describe deep same-sex devotional bonds in early Christian communities, where language of love between men was intense, embodied, and covenantal.

We can't retroactively assign a modern identity category with certainty. But we can say this:

Valentine becomes a patron saint of those who love against the law.

In that sense, he stands in the lineage of queer sanctity—love that refuses state control, love that forms kinship outside sanctioned structures.

Lupercalia: Wolves, Fertility, and the Pack

Before the feast of St. Valentine was fixed on February 14, mid-February in Rome belonged to Lupercalia.

Lupercalia was held in honour of Romulus and Remus, the twins said to have been suckled by a she-wolf, and of the pastoral god Faunus.

Priests called Luperci sacrificed goats and a dog, cut strips of hide, and ran through the city striking women who presented themselves. This was believed to promote fertility and safe childbirth.

It was sensual. It was wild. It was public.

But it was also embedded in a Roman imperial structure that depended on conquest, enslavement, the control of women's lives and bodies, and the absorption—often destruction—of local spiritual traditions across the Mediterranean and beyond.

Rome was a devourer of gods.

The wolf pack was not innocent. It was expansionist.

The Horned One at the Edges

When we trace deeper into European and Mediterranean religious imagination, we encounter the horned god—part goat, part human, liminal, erotic, destabilizing.

The Greek god Pan embodies this threshold energy. Wild music. Sudden fear (panic takes its name from him). Sexuality that does not fit polite civic order.

Later Christian demonology would conflate horned deities with the Devil, turning nature and erotic power into something suspect.

The horned figure is often androgynous in symbolic form—crossing boundaries between masculine and feminine, culture and wilderness, human and animal.

This liminality is not chaos for its own sake; it is a gathering force. The one who plays the pipe calls the scattered back into a circle.

The Bacchae and the Edge of Ecstasy

In The Bacchae by Euripides, the god Dionysus returns to claim recognition. The women leave the city and enter the mountains in ecstatic ritual.

The play is not propaganda. It's a warning.

Ecstasy can liberate. It can also unmoor.

The refusal to honour the god leads to catastrophe—but so does unintegrated frenzy. The tragedy holds both truths at once: repression breeds violence; so does uncontained rapture.

For us, the Bacchae are a reminder: howl, yes—but know your ground. Build containers. Stay in relationship.

Howl but know your ground. Build containers. Stay in relationship.

Shared Terrain: Pan and Dionysus and Love That Disrupts

The relationship between Dionysus and Pan is not genealogical in any consistent mythic sense.

Their connection is thematic, ritual, and atmospheric.

Dionysus is the god of wine, ecstatic trance, theatre, and the dissolution of rigid identity.

Pan is the pastoral god of shepherds, wild spaces, sudden fear, rustic music, and sexual vitality.

Where Dionysus destabilizes the city from within—appearing in Thebes in The Bacchae to demand recognition—Pan lives mostly outside it, in caves, groves, mountains.

One breaks boundaries socially.

The other erodes them ecologically.

Ecstasy and Embodiment

Dionysian ritual (thiasos) involves collective ecstasy: dancing, drumming, altered states, the loosening of ordinary consciousness. His followers—the Maenads and Bacchants—enter a shared religious frenzy.

Pan’s domain is more solitary and erotic. His pipe music seduces, startles, and unsettles. His energy is immediate and bodily—goat-legged, horned, unapologetically sexual.

Dionysus dissolves the ego into group trance.

Pan intensifies instinct in the individual body.

Yet both operate at the threshold between civilization and wilderness, reason and instinct.

Dionysus is associated with drums, flutes, and ecstatic choral song.

Pan invents the syrinx (panpipes), whose sound carries across valleys and unsettles shepherds at dusk.

Music is the bridge. Both call bodies into altered awareness through rhythm and breath.

Listening. Breath to move the air in waves that move through the Other, and somehow change them.

Fear and Liberation

The word “panic” derives from Pan: the sudden, groundless terror that can overtake travellers in lonely places.

Dionysus also produces madness—but in a ritual frame. In The Bacchae, the king Pentheus resists him and is destroyed by forces he refuses to honour.

In both cases, repression breeds rupture.

They are gods of what happens when instinct is denied.

Cult and Historical Context

In historical Greek religion, Dionysus had major civic cults, festivals (like the Dionysia), and theatrical institutions built around him.

Pan’s worship was more localized and rustic, though he gained broader popularity after the Battle of Marathon, when Athenians credited him with inspiring panic in the enemy.

Pan is more archaic in tone.

Dionysus becomes more politically and socially integrated.

Later Convergence

In later Hellenistic and Roman thought, both figures contributed to the imagery that Christianity would later fold into the iconography of the Devil: horns, hooves, sexual energy, wilderness.

They become symbols of untamed nature and bodily ecstasy—precisely what institutional religion sought to discipline.

In Spiritual Archetype

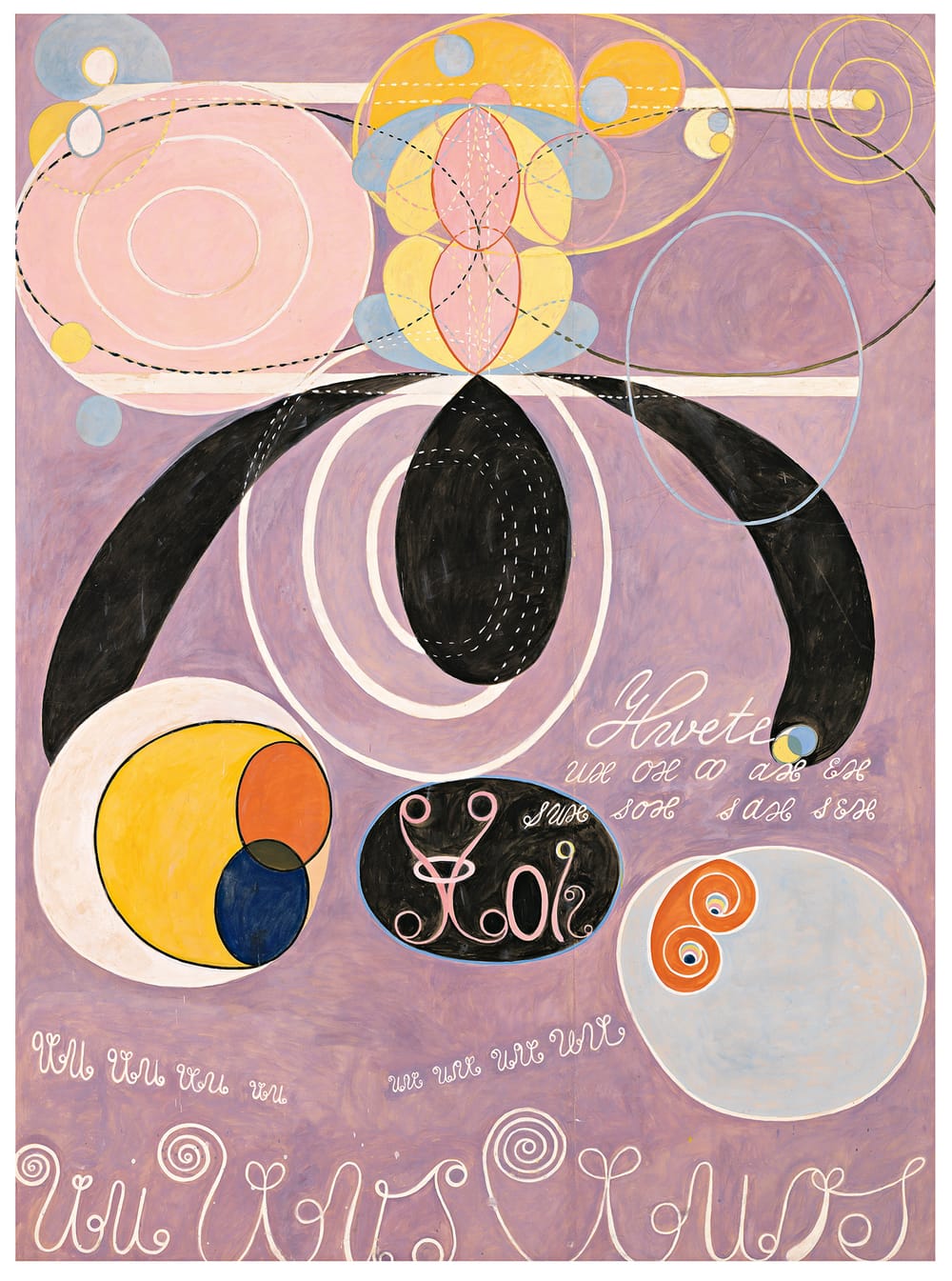

What do these horned and ecstatic gods have to do with February 14? Not chocolates. Not compulsory coupledom. But the older pulse beneath the calendar: rites that marked the body as sacred, that unsettled rigid roles, that gathered people into forms of kinship not defined by the state. The mid-February festivals of Rome—before they were softened, suppressed, or sanctified—belonged to this same threshold season. To remember Dionysus and Pan alongside the wolf-rites of Lupercalia is not to collapse them into one lineage, but to recognize a shared grammar: love and desire as forces that exceed law, ecstasy that asks for container, and the perennial human hunger to find one’s pack in the dark of winter.

If we step back from strict mythology and look symbolically:

- Dionysus represents sacred intoxication, collective transformation, the breaking of rigid identity.

- Pan represents raw instinct, erotic aliveness, the shock of wilderness.

They are cousins in the grammar of liminality.

Both ask:

What happens when the boundaries of the self loosen?

What happens when we let the wild in?

One gathers the crowd into ritual ecstasy.

The other meets you alone in the forest and plays a note that changes your breathing.

Together, they map two paths to the same edge.

Rome, Repression, and Distortion

In calling up Love and it's saints and GODDETCs today, we might also remember Venus, Rome’s goddess of love, whose Greek counterpart Aphrodite carried a beauty as dangerous as it was generative.

Venus was not only patron of desire but mother of imperial lineage, claimed as ancestor by Rome’s ruling class. Love here is not rebellion but foundation — the force that builds dynasties and sanctifies inheritance.

Aphrodite, for her part, could just as easily ignite war as wedding. To place them beside wolves, saints, and horned gods is to admit that eros has never been innocent. It gathers, it destabilizes, it legitimizes, it destroys. February carries all of it: love that founds empires, love that defies them, and love that slips its leash entirely.

As Rome expanded, it absorbed and standardized. As Christianity consolidated power, it suppressed or reinterpreted earlier practices—especially those centring women’s ritual authority, erotic autonomy, and non-state kinship.

Much of what we now imagine as “ancient pagan love festivals” is already filtered through imperial and later Christian narratives. Indigenous European practices were not static; they were complex, local, and often erased.

So when we speak of “pagan roots,” we have to step carefully. There is no pristine past to return to. Only fragments, and the ethical responsibility to not romanticize empire.

What We Can Conjure Now

When we follow the threads of Lupercalia, the horned gods, and the martyrs named Valentine, we encounter still deeper currents: the sovereign, generative energy of Gaia and Cybele, the mother cults excised from ancient Greek plays, but alive in the margins, in pot fragments and threshold altars and doorways.

A love beneath and beyond.

An energy that remains through thousands of years of instrumentation to remind us that love is not only desire between two bodies; it's the pulse of community, the protection of kin, the nurture of land, the rites that gather beings, adults and children, into cycles larger than themselves.

It lives in the wolf pack that runs together in the dark, in the sweets and shared meals that mark February gatherings, in the whispered truths told in circles that survive empire, erasure, and commercialization.

This love is alive, subterranean, and liminal — it teaches us to see, to listen, to recognize who will run with us, who will honour our ecstatic truths, and who will share the earth beneath our feet. It is a love that refuses simple boundaries, that blooms in both shadow and fire, and that continues to call us back to the places and people where we truly belong.

If there is something worth reclaiming, it's not goat-skin lashes in the street.

It is this:

• Love that defies coercive power.

• Community formed outside rigid structures.

• The courage to name desire honestly.

• The willingness to find your pack.

To “run with the wolves” now might mean telling your strange truth and seeing who steps closer instead of away.

It might mean refusing compulsory romance and honouring chosen kin.

It might mean dancing at the threshold between identities—gendered, spiritual, cultural—without collapsing into spectacle or losing your footing.

The horned god(dess) is not an excuse for harm. They arean invitation to inhabit the edges consciously.

The saint of forbidden unions is not a mascot for greeting cards. He is a reminder that empire always tries to regulate love.

A Closing Spell for Today

May you find the ones who recognize your howl.

May your ecstasy be grounded.

May your love refuse the empire inside and outside you.

May you move through the liminal spaces without losing your name.

And may February not be about consumption—but about covenant.

Further Reading

Here are texts and scholarly resources that offer deeper grounding for the themes explored above:

Historical overviews and academic context

- “Lupercalia” — Encyclopaedia Britannica article offers an overview of the festival’s rituals and historical context. Lupercalia (Britannica)

- “Valentine’s Day” — Wikipedia’s survey of the feast day’s history, including discussion of Valentine’s feast and associations with mid-February pagan rites. Valentine’s Day origins (Wikipedia)

- Gregory Wakeman, Valentine’s Day Has a Dark, Bloody Precursor — A recent History.com exploration of Lupercalia’s social role and legacy. Valentine’s Day and Lupercalia (History.com)

Primary texts and classical sources

- Plutarch’s Lives and Roman Questions (for narrative sources on Lupercalia and Romulus and Remus).

- Ovid’s Fasti (for Roman calendar rites).

- Euripides, The Bacchae (for mythic exploration of ecstasy and community).

On Lupercalia and Roman Religion

- Wolves of Rome: The Lupercalia from Roman and Comparative Perspectives by Krešimir Vuković (De Gruyter, 2018).

Academic monograph examining Lupercalia in Roman and comparative Indo-European contexts. - Religions of Rome, Volume 1: A History by Mary Beard, John North, and Simon Price (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

A foundational scholarly history of Roman religion. - Religion of the Romans by Jorg Rupke (Polity, 2007; originally German 2001).

Academic synthesis of Roman religious practice and its social embeddedness. - Literature and Religion at Rome by Denis Feeney (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Study of Roman literary representations of ritual life.

On Chaucer and Valentine’s Day

- The Parliament of Fowls by Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1380s).

- Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine by Henry Ansgar Kelly (Brill, 1986).

A scholarly monograph specifically focused on how Valentine’s feast became associated with romance. - Jack B. Oruch, “St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February,” published in Speculum 56, no. 3 (1981): 534–565.

Peer-reviewed article arguing that the romantic Valentine tradition likely originates in Chaucer’s milieu rather than ancient pagan continuity.

On Greek Religion and Ecstasy

- Greek Religion by Walter Burkert (Harvard University Press, 1985).

A canonical modern study of Greek cult practice, including Dionysian religion. - Women's Life in Greece and Rome edited by Maureen B. Fant and Mary Lefkowitz (Johns Hopkins University Press, multiple editions).

A respected sourcebook of translated primary texts on gender and ritual in antiquity.