Across cultures and centuries, the word witch has been used to describe — and often accuse — people whose knowledge, bodies, or ways of living could not be controlled. Witches were healers, midwives, land keepers, artists, and outsiders. They were also people marked as dangerous during times of fear, scarcity, and social change.

Today, the witch has been reclaimed by people of all genders as a symbol of autonomy, care, resistance, and connection to the living world. Modern witchcraft draws on history, ritual, art, music, and community — often practiced in covens or loose circles — to challenge systems that profit from disconnection from each other, from the earth, and from our own power.

This guide explores what a witch is, what a coven is, the history of witch trials, and why the witch still matters today — in feminism, pop culture, contemporary spirituality, and collective resistance. Whether you’re curious, cautious, or already feeling something stir, this is a place to begin.

Table of Contents

- What Is a Witch? History, Identity, and Power

- The Malleus Maleficarum and the Invention of the Witch: Text, Law, and Fear

- The Witch Trials of the 16th and 17th Centuries

- Witches’ Sabbath: the Devil, and Fear of the Body

- From Fear to Celebration: The Witches’ Sabbath Today

- Witches' Familiars: Transformation, Kinship and Magical Powers

- The Witch Reclaimed

- The Witch In Feminist and Post-Colonial Theory

- Witches in Music

- Witches in Film and Contemporary Art

- Witch Hunts Aren't History

- Who Is the Witch Today?

- What Is a Coven?

- What is a Witch? What is a Coven? A poem/manifesto

- TL;DR: Common Questions About Witches and Covens

What Is a Witch? History, Identity, and Power

The word Witch has never been neutral — but it's always been magnetic. Across medieval and early modern Europe, through the witch trials of the 16th and 17th centuries, and into modern witch identity and popular culture, the witch has carried our deepest fears and longings. She appears wherever people worry about autonomy, about knowledge that lives outside institutions, about nature based power and what happens when people gather without permission. If you feel curious, comforted, or unsettled by the word, you’re not alone. That pull is part of the story.

Many witches never called themselves witches at all. They were neighbours, healers, widows, midwives, caretakers. During periods of crisis, they became suspected witches, blamed for illness, loss, or change, and accused of magical powers, black magic, or witchcraft beliefs they did not invent. The witch trial was less about what someone did, and more about who they were allowed to be.

As common land was seized and shared life was broken apart, control over women’s bodies increased too. As European empires expanded, this same logic travelled the world. Colonizers labelled Indigenous and African spiritual practices as pagan religion, devil worship, or witches and witchcraft, using fear to justify land theft, forced conversion, and violence. The witch became a figure used to police bodies, break community bonds, and separate people from land — at home and across the globe.

This page is an invitation to look again. To ask: What is a witch? What is a coven? And why do these words still matter? Here, you’ll find history, myth, and living practice braided together — not to scare you, but to make room. The witch is not a threat hiding in the shadows. She is a reminder of what survives when people choose memory over fear, and connection over isolation. Welcome.

The Malleus Maleficarum and the Invention of the Witch: Text, Law, and Fear

In 1487, a book helped lock the witch into place. The Malleus Maleficarum — Latin for “Hammer of Witches” — was written by clerics and widely circulated across Europe. It claimed to offer proof of witches and instructions for identifying and punishing them.

The book insisted that witches:

- were inherently deceptive

- were especially female

- practised black magic

- entered pacts to worship the devil

What’s important is this: the Malleus Maleficarum did not record existing witchcraft beliefs. It created them. It trained judges, priests, and officials to see women’s anger, sexuality, illness, or independence as evidence of evil. Scholar Silvia Federici notes that texts like this turned misogyny into law, embedding fear into legal and religious systems for centuries.

This is how the witch became a monster on paper — and a target in real life.

Suggested Episode: Dr. Marion Gibson - It Almost Feels Like They Are Waiting There For You

A witch is most often - not always - female; typically poor, disabled or ill, sexually subversive (according to their time and place), viewed as politically dangerous for either their beliefs or their mere identity.

The Witch Trials of the 16th and 17th Centuries

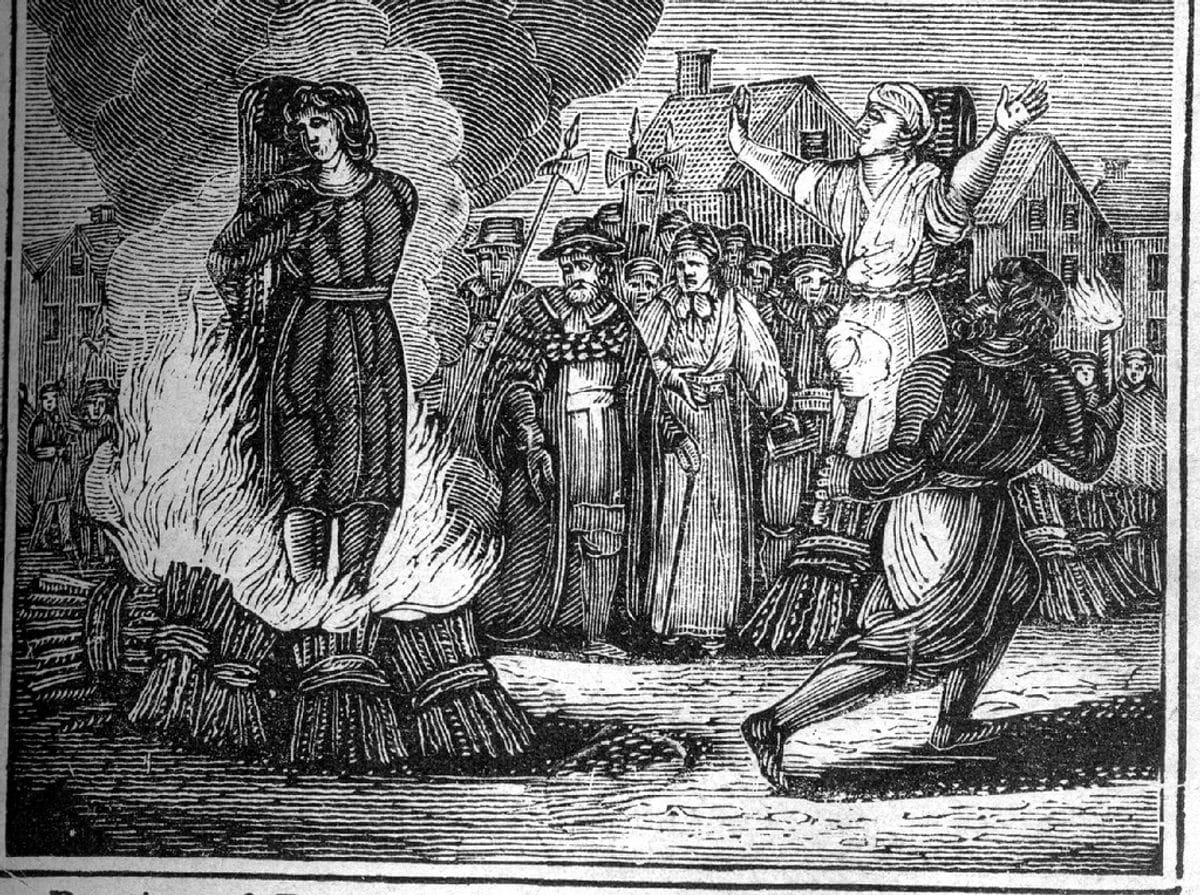

The explosion of witch trials during the 16th and 17th centuries marks a turning point. Tens of thousands of accused witches — the majority of them women — were interrogated, imprisoned, tortured, and executed across Europe and colonial territories. This was not a sudden outbreak of madness. It was a slow, grinding violence that grew alongside major shifts in how power worked.

The trials intensified during moments of deep instability:

- enclosure of common lands

- religious upheaval and reform

- colonial expansion

- famine, plague, and economic collapse

Feminist and historical scholars have helped us see that witch hunts were not random fear, but organized violence shaped by politics, economy, and gender. In Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici calls the hunts “a war against women,” linking them to the rise of capitalism, the enclosure of common land, and new control over women’s bodies and reproductive labour. Marion Gibson, in Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe: 13 Trials, provides rich case studies showing how accusations targeted women who were independent, outspoken, or outside patriarchal protection, illustrating how legal systems codified fear and punishment. Similarly, Carol Karlsen’s The Devil in the Shape of a Woman highlights colonial New England, where women without property or male guardianship became especially vulnerable, showing that independence itself could mark a woman as dangerous.

Concerns about desire, sexuality, and the body shaped accusations in Europe as much as economics and law. Lyndal Roper, in Witch Craze, traces how these anxieties infused legal and cultural narratives.

Suggested Episode: Tituba - Do You Know What A Witch Really Is?

Tituba is perhaps the most famous name of the Salem Witch Trials, but at the same time, very very little is known about her.

Witches’ Sabbath: the Devil, and Fear of the Body

Stories of the witches sabbath — secret nighttime gatherings filled with sex, feasting, flight, and devil worship — were stories extracted under torture and repeated by those in power.

The sabbath condensed elite fears about:

- women gathering without supervision

- pleasure outside reproduction

- bodies beyond discipline

- collective ritual and joy

Accusations of witches who worship the devil allowed church and state to turn social resistance into spiritual corruption. A woman who danced, laughed, healed, or gathered others could be recast as dangerous. As theorist Silvia Federici puts it, the witch’s body became “the site of a political struggle.”

These stories weren’t about belief. They were about control.

Suggested Episode: Dr Phyllis Rippey: I Started To See Breastfeeding As Central To The Construction Of Gender

If breastfeeding people can have these little beings who see them as all providing and all-knowing, it’s almost although only those people can experience what it’s like to be a God… and so we start to see a control of women’s bodies.

From Fear to Celebration: The Witches’ Sabbath Today

While stories of witches’ sabbaths once fueled fear of women’s bodies, desire, and collective power, modern Wiccans and other contemporary witches have reclaimed and reimagined these gatherings. They trace a year of rituals through eight sabbats, forming the Wheel of the Year — a cycle of seasonal celebrations that honour the living world, ancestral knowledge, and the rhythms of nature.

Today, witches still revere, reinterpret, or play with these ancient and invented high holidays, using them as opportunities for community, reflection, and joy.

For those interested in exploring how contemporary practitioners mark these moments, check out our collection of podcast episodes celebrating the sabbats: Sabbat Specials.

Witches Familiars: Transformation, Kinship and Magical Powers

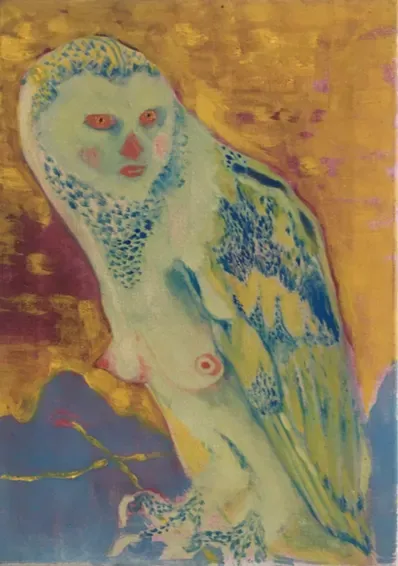

Many witches were accused of having familiars, talking with animals and taking animal form — becoming cats, wolves, hares, owls, or birds. These accusations framed transformation itself as a threat: crossing boundaries between human and animal, domestic and wild. Magical powers were imagined as contamination. The witch didn’t learn power — they carried it, leaked it, spread it. They escape bodies, binaries, species.

From a Missing Witches lens, transformation looks like adaptation, survival, and kinship with the more-than-human world. The witch who turns into an animal isn’t escaping humanity — they’re reminding us we were never separate.

In reaching for animal and plant relation, modern witchcraft has also often relied on extraction from Indigenous cultures — white sage, palo santo, and spirit animals are examples of practices too often adopted without accountability, perpetuating colonial histories. At Missing Witches, we're just trying not to fuck this up too much. We ground our practice in reparative work. Each May, we donate our entire income from our coven and organize an annual reparations fundraiser — to date raising over $50,000. We prioritize connection through story, relation, conversation, and material repair, learning from Indigenous and marginalized knowledge with love, respect and accountability.

When we get it right, we explore transformation through relational practices — with animals, plants, ecosystems, and our many selves — showing how wildness, interconnection, and reverence continue to animate magical practice in the present.

For those interested in going deeper with practicing witches meditating on relationships with their more-than-human-kin, check out our Kinship Series.

The Witch Reclaimed

Reclaiming tradition has long been central to contemporary witchcraft. In the 1970s, Starhawk and other feminist practitioners drew on older pagan and Earth-based practices to craft rituals that honoured women’s power, community, and the natural world. Archaeologist Marija Gimbutas’s work on Neolithic Europe and the concept of an ancient matriarchy provided inspiration for imagining histories of female-centered spirituality, challenging narratives that had erased women’s roles in shaping culture and ritual.

Contemporary witches continue this lineage in diverse ways. Amanda Yates Garcia raises questions of accountability and justice in magical practice, while Pam Grossman explores witches as agents of creativity and resistance. Artist, Indigenous practitioner, and “mutant” witch Edgar Fabián Frías expands the field further, blending ancestral knowledge, radical imagination, and personal innovation, highlighting how witchcraft can be practiced as an act of cultural reclamation, and radical self-determination.

At Missing Witches, this work comes alive through conversations, interviews, and explorations of creative practice — from art to music, ritual to storytelling. For examples of how contemporary practitioners trace these paths today, see our Best Witch Podcasts collection, where witches share their insights, practices, and visions of a world re-enchanted.

Suggested Episode:

Indigenous Futurism: Edgar Fabián Frías + Chrystal Toop

Who gets to create the dreamworld? What do we want to have realized when we're already there?

The Witch In Feminist and Post-Colonial Theory

Jules Michelet’s 19th-century La Sorcière romanticized the witch as a folk healer, midwife, and symbol of popular resistance — an archetype that would be embraced, expanded upon and critiqued by feminists like Barbara Ehrenreich and Dierdre English in Witches, Midwives and Nurses: A History of Women Healers. Hélène Cixous and Catherine Clément examine how hysteria and the figure of the witch encode fears of women’s power, creativity, and collective knowledge, highlighting that the “evil” attributed to witches often mirrors anxieties about female autonomy.

The witch reaches across social and geographic lines, as María Tausiet’s work on early modern Spain demonstrates. Accusations functioned as social discipline, targeting poor or marginalized people during periods of instability.

Post-colonial theorist Sylvia Wynter reminds us that these patterns of exclusion continue globally: colonial systems decide who counts as fully human, and the figure of the witch marks those deemed disposable or dangerous. Black feminist scholarship, including Saidiya Hartman (Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments) and Oyèrónkẹ́ Oyěwùmí (The Invention of Women), helps extend this understanding, historical witch hunts connect to broader systems that police bodies, knowledge, and survival itself.

The witch was invented in part by systems that feared autonomy, shared knowledge, and lives lived beyond control. She is a figure of resistance, survival, and embodied knowledge — a reminder that power often lives where we least expect it: in women, in communities, in memory, and in the wild spaces between.

Suggested Episodes:

Urduja: You Are Kapwa, Kin, Connected To Everything

"The witch hunts were a trauma against women and against the earth, and against a worldview that saw holiness and spirituality as the birthright of every being. They were also a weapon in the global violence of colonialism."

María Sabina: I Am The Woman Who Shepherds The Immense

"If you have been hunted and slandered for your healing and your magic and your deep knowledge of the power in the natural world, then you are a part of the history that the world has been missing and that we want to gather here to honour with the turning of the wheel of the year."

Witches in Music

The witch in music is a figure of power, resistance, and transformation. Across decades and genres, artists have drawn on witchcraft, mystical imagery, and spiritual practice to explore desire, autonomy, and rebellion — giving listeners a space to feel collective and personal power.

Florence + The Machine uses the archetype of the witch to explore female experience, sexuality, and resilience. In Dance Fever (2022), historical phenomena like choreomania (dancing plagues) inspire songs that connect ecstatic movement, oppression, and liberation. Tracks like “Witch Dance” (Everybody Scream, 2025) step through life-altering thresholds, “Everybody Scream” celebrates refusing to be quiet or constrained, and “One of the Greats” uses resurrection imagery to critique misogyny in the music industry. Across albums, Florence transforms the witch into a figure of collective agency, inviting audiences to move, scream, and claim power together.

Björk channels witchy archetypes through avant-garde experimentation and ritualized performance. Her first band, Kukl, took its name from the Old Icelandic word for witchcraft, and songs like “Pagan Poetry” (Vespertine) weave pagan imagery with sexuality and transformation. Björk’s work shows how witchcraft can be a space for personal and collective empowerment, connecting mystical narrative with emotional and sonic intensity.

For Black artists, witchcraft and spiritual symbolism often intersect with traditions targeted by colonial and patriarchal violence, creating layered forms of resistance. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and Nina Simone used “I Put a Spell on You” to channel theatrical, blues-infused magic, turning spellcraft into a performance of power. Jimi Hendrix blended Black American spiritual symbolism with supernatural themes in songs like “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)”, embodying a confrontation with unseen forces and cultural oppression. Contemporary artists like Azealia Banks openly reference brujería and Santería, while Beyoncé has been accused of “dark magic” by detractors — a reflection of how women of color claiming autonomy are often framed as dangerous.

Rock and post-punk artists such as Fleetwood Mac / Stevie Nicks, Donovan, Black Sabbath, and Siouxsie and the Banshees use occult imagery to shock, challenge norms, or celebrate transgression, demonstrating that witchy power resonates across audiences. Across all these traditions, the witch is less about literal spellcasting and more about embodying resistance, reclaiming agency, and challenging systems that seek to control bodies, knowledge, and desire. Whether through ritualized performance, pagan symbolism, or African diasporic spiritual practice, the figure of the witch continues to inspire collective exhilaration, autonomy, and defiance.

Suggested Episodes:

YOKO ONO - Smash Your Preconceptions

Everyday life is full of rituals. When you do them consciously, when you perform them with intention, they become magic.

Alice Coltrane - Spritual Jazz

In 1972, she told DownBeat magazine, "I would go through all the great scriptures of the world, and in every religion I found the same thought: 'The divine sound is the creative force in the universe.' Music is that sound."

Explore more with our collection on Sonic Witchcraft.

Witches in Film and Contemporary Art

Witchcraft in film and art is more than spectacle — it’s a lens for exploring autonomy, rebellion, and cultural resistance. Shows like Wicked, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, The Discovery of Witches, and films like The Craft are thrilling gateways for many into witchy worlds. But beyond these pop hits, witches continue to run through deeper, less commercial veins of culture, defining creative expressions of deviance, power, and social critique.

Artists often reclaim historical witch hunts to confront oppression. Rachel Rose’s Wil-o-Wisp links witch narratives to land enclosure and environmental change, while Delaine Le Bas’s Untouchable Gypsy Witch confronts marginalization, displacement, and cultural erasure. Alejandra Hernández and other feminist artists celebrate female power, nature, and ritual, drawing on ideas from Silvia Federici to challenge the male-centered “rationality” of modernity.

Installation and performance also allow witches to speak in monumental ways. Jesse Jones’s Tremble Tremble uses film and live performance, including a towering giantess figure, to explore silenced Irish witchcraft histories, turning the witch into a monumental, defiant presence. The collective W.I.T.C.H. Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell centred guerrilla theatre and performance art like hexing Wall Street in 1968 to investigate witchcraft as a framework for community ritual and resistance.

Film continues to explore these themes across genres. Midsommar (2019) and Suspiria (1977 & 2018) use ritual, horror, and dance to interrogate female agency, desire, and collective power. The Witch (2015) evokes early modern anxieties about female autonomy, faith, and social order, while more experimental works like The Love Witch (2016) foreground witchcraft as critique, spectacle, and empowerment. Across film and art, witches embody resistance, ecstasy, and power beyond prescribed social norms, bridging past and present in vivid, transformative ways.

Suggested Episodes:

Hilma af Klint + Anna Cassel - Life Is A Farce If A Person Does Not Serve Truth.

In this story, a missing artist, a Swedish woman named Hilma gets added to the pantheon of greats, and then in an attic, in dusty archive, other journals by other women are found, artists, channellers, nurses, lovers, point after point in this constellation are discovered and the story of the lone genius is spiraled open. This is a story about emergent properties like love and inspiration, and beautiful beautiful beautiful paintings.

Amy tells the story of W.I.T.C.H. Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell – a group that sprung up from the Women’s Liberation movement in 1968 New York, on Halloween, to hex sexism, capitalism and racism. A group who’s legacy is still visible today.

Explore more with our collection on Art Witchcraft.

Witch Hunts Aren't History

Witch hunts aren't just history. Today, people — mostly women — are still attacked, exiled, or killed after being accused of witchcraft. Contemporary witch hunts occur in parts of Africa, South Asia, Latin America, and within diasporic communities worldwide. They often target older women, widows, disabled people, or anyone who stands outside family or economic control. Post-colonial scholars point out that these accusations intensify during times of crisis: land disputes, climate change, poverty, or political instability. The pattern is familiar. When systems fail, blame moves downward. The “witch” becomes a way to explain loss without challenging power.

At the same time, the logic of the witch persists in cultural and political discourse. Public figures who speak, act, or perform independently — especially women in music, film, or activism — can be demonized. Hysterics from conservative religious communities screamed "Witch" in response to Taylor Swift's use of coven imagery in the Evermore portion of the Eras Tour, framing her exploration of sexuality, power, and autonomy as devilish, dangerous, threatening. Donald Trump churns the waters of his followers towards misogynist violence using “witch” as a pejorative for women who criticize him, even while advocating policies that harm women’s rights.

The connection is subtle but real: in both life-threatening and symbolic ways, women who claim independence, knowledge, or influence continue to attract fear and punishment. The figure of the witch becomes a shorthand for anxiety about women stepping outside prescribed roles — whether through survival, leadership, or art. Understanding this helps us see that the legacy of the witch is not just historical or metaphorical; it's a continuing lens on power, fear, and the policing of women’s lives.

This is why the word still matters. When a society fears autonomy, common knowledge, common land, or women and other gendered bodies who do not comply, it reaches for old archetypes. The witch is cast as evil, dangerous, or contagious — someone to be watched, punished, or removed.

Missing Witches exists to interrupt that story. To remind us that what gets called “evil” is often just uncontrolled, and what gets called “magic” is often care, memory, and survival practiced together.

Your witchy neighbour is not the threat.

The story that taught you to fear her might be.

Consider supporting organizations like End Witch Hunts, which works to protect accused individuals, raise awareness, and challenge the social and political systems that perpetuate witch hunts today.

Who Is the Witch Today?

We started Missing Witches because we were looking for these people, whether they claimed the word Witch or not: marginalized thinkers, artists, activists, shopkeepers, diviners, dancers, hearth keepers, parents, poets, and teachers — anyone carving new paths to connection with the living world, with oppressed communities, and with knowledge that has been suppressed or forgotten about how to use our will to dance with the emerging world.

Witches resist a culture that insists they are not enough, that accumulation is sacred, and that other people — and the earth itself — are objects of fear or control.

The witch today is someone re-enchanting their world. They may write, paint, or perform; tend gardens, forests, or hearths; teach, heal, or commune with spirits; build communities of care; or practice divination. As Edgar Fabián Frías reminds us, “the witch is self-ordained” — defining their own path, authority, and power on their own terms. They are often in dialogue with the past — honouring the lives of women, gender-diverse people, men, and other marginalized figures who survived persecution — while inventing practices and spaces that sustain life, creativity, and resistance in the present.

Through Missing Witches, we’ve interviewed hundreds of people who identify as witches or who teach us about our own craft. These conversations show that the witch is fluid, intersectional, and expansive: they can be a musician invoking ecstatic power, an artist transforming trauma into ritual, a parent nurturing defiance and resilience in children, or a healer reclaiming ancestral knowledge. They remind us that magic is not fantasy; it is a framework for survival, autonomy, and deep connection — to themselves, to each other, and to the world they inhabit.

Meet hundreds of modern witches as well as artosts, activists, researchers and ritualists inspiring our own witchcraft in our interview series, Witches Found.

What Is a Coven?

Much of the popular idea that witches gather in covens of thirteen comes from Margaret Murray, the pioneering (and sometimes problematic) archaeologist and folklorist. In her book The Witch-Cult in Western Europe, Murray proposed that pre-Christian communities had organized, joyful systems of worship, centred on a goddess and connected to the earth and animals. While her methods and conclusions have been heavily critiqued, her work left a lasting imprint on modern witchcraft. At Missing Witches, we dedicate an episode to her: “Margaret Murray: What Science Calls Nature and Religion Calls God,” exploring her life, contradictions, and her role in shaping the idea of the coven. She was a feminist, a trailblazing archaeologist, and a witch in her own right — fiercely connected to the past and unafraid to follow her intuition where the sources led.

Today a coven is a community of witches who come together to share practice, knowledge, and support. Covens can be formal or informal, large or small, online or in person. Members might gather for ritual, to raise power, study, make art, organize activism, or enact mutual care. Covens create a space to explore magic, spirituality, and connection to the living world.

In Wiccan tradition, covens are often structured around the Wheel of the Year, celebrating eight sabbats that mark the seasons, cycles of life, and the rhythms of nature. Wiccan covens may work with ritual, spellcraft, and meditation, emphasizing collective energy. Members often take on roles — such as high priest, priestess, or initiates.

Covens in the Crowleyan or ceremonial magic tradition (linked to Aleister Crowley and Thelema) often emphasize ritual precision, initiatory grades, and formal magical practices. These covens explore esoteric knowledge, ceremonial spellcraft, and symbolic systems, and they may include study of astrology, Qabalah, or alchemy. While more structured, Crowleyan covens still center on shared growth, spiritual practice, and the disciplined pursuit of magical insight.

When looking for a coven, it’s important to protect yourself. Ask about gender roles, consent protocols, and boundaries around ritual participation. Make sure the community respects your autonomy, and that you feel safe asking questions, exploring, and leaving if the space doesn’t feel right.

At Missing Witches, our coven blends learning, play, ritual, and radical care — supporting each other while opening pathways for anyone seeking community, empowerment, and shared magical practice, whether they identify with Wicca, ceremonial magic, or their own eclectic path.

What is a Witch? What is a Coven? A poem/manifesto

by covenmate Jasmin Stoffer.

What is the use of a coven? This coven?

How do we keep it from becoming just an echo chamber—of patronizing agreement, stagnant admiration, and surface-level celebration?

How do we, as witches, hold space for critique and self-reflection within the coven, while keeping the circle safe and welcoming for the diverse and magical bodyminds who gather here?

Shout out to the fellow Missing Witches coven member who sparked this line of thought. Proof, if we needed it, that covens are both:

A space for magical delight, for our vibes, our rituals, our gorgeous, witchy selves

And

A cauldron for deeper, more reflexive practices that ask: Where has the witch been? How have they been seen? And what does it mean, truly, to be a witch today?

I’ve written before: Witch is a verb.

The word conjures a thousand images; black hats, moonlit rituals, bones and candles, or for those who don’t think in pictures, perhaps a set of feelings, tensions, or senses… all shaped by dominant culture, colonialism, and capitalism.

And now, thanks to social media, Witch has become an aesthetic. A whole damn vibe. It’s whatever a witchy person wants it to be.

But for me?

It is first and foremost an action.

To say “I am a witch” is to choose a certain kind of life:

One of outsiderness.

Of subversion.

Of so-called wickedness.

Because this world we live in? It was built on the pyres (both literal and figurative) that burned our outspoken, oppressed, outsider, activist ancestors. And today, those same flames are still fanned, still feared, still used to power the systems that harm.

The witch’s work is to extinguish those fires and to let the structures built on the ash, collapse.

So, if you’re going to call yourself a witch; prepare yourself.

Learn our history. Understand that in many parts of the world, people are still persecuted for this identity. And know that witchcraft is activism.

Activism is not a buzzword. It’s not (just) a hashtag.

It’s vigorous action; an intense, intentional practice of transformation: of the self, the space, the society, the coven.

This is witchcraft.

And let’s be clear: aesthetics are not the witch’s primary concern.

And not everyone who wants to be a witch or who currently identifies as one is necessarily ready for the full weight of that word.

Because witchcraft comes with history. Long, tangled, bloodied, beautiful threads that cannot be cut.

If we are to be witches, then we must make space and build strength to carry that history.

All of it.

And we must do so together.

That’s what the coven is for.

The coven is a sanctuary.

The sabbat space.

The circle we enter to breathe and rest, to dream and doubt, to mourn and make merry.

It is where we lay down our grief and raise up our power.

It is where we gather; to build plans and break spells, to nourish ourselves and one another before stepping back out into the burning world.

When the circle opens, we step in.

When the circle closes, the work continues.

And we must be ready.

Because it never stops.

And so it is.

So it always will be.

Coven and community.

Hive and helpers.

Wicked and wonderful witches.

Carrying the work forward, spell by spell,

brick by brick,

by flame and ash, by light and shadow.

Changing the world so the circle may continue—

for the next of us.

And the next.

And the next…

Blessed fucking be.

Jasmin (she/her/they/them) is a disabled settler, educator, activist, and community member based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. A PhD candidate at St. Francis Xavier University, their research explores anti-ableist pedagogy, disability justice, and teacher education. Jasmin is a co-founder of the Disabled Educators' Curriculum Collective (DECC) and is a member of several disability activist groups in her community. Their evolving witchcraft practice draws on pre-Christian European (Dutch, Bavarian, Hungarian) roots. Find their reflections on life, public education, ableism, and advocacy on social media. Bluesky - jastoffer.bsky.social / Instagram: @jaurora8

TL;DR: Common Questions About Witches and Covens

What is a witch?

A witch is someone who works with magic, ritual, and spiritual practice to connect with the living world, community, and themselves. Witches can be women, men, non-binary, or genderfluid — the label is self-defined, as Edgar Fabián Frías says, “the witch is self-ordained.” Historically, the word has been used to target independent or marginalized people, but today it’s reclaimed as a symbol of autonomy, knowledge, and care.

What is a coven?

A coven is a community of witches who gather to practice magic, share knowledge, and support each other. Coven sizes, structures, and traditions vary — from informal groups of friends to Wiccan or Crowleyan covens with formal rituals. Modern covens often focus on shared practice, seasonal celebrations like the eight sabbats, and ethical exploration of magical arts.

Are witches real?

Yes. Witches are real people practicing spiritual, ritual, and magical traditions across the globe. Magic here isn’t fantasy; it’s often a framework for survival, connection, care, and resistance to systems that limit autonomy or oppress marginalized communities.

Is being called a witch dangerous today?

Witch hunts are not just history, accusations can still lead to violence or exile. In cultural and political contexts, the term can be weaponized against women, activists, or independent artists, echoing centuries-old patterns of fear and control. Supporting organizations like End Witch Hunts helps protect people at risk.

How can I find a coven safely?

Look for groups that respect consent, boundaries, and personal autonomy. Ask about gender roles, initiation practices, and how the group handles participation in rituals. Make sure you feel safe asking questions and leaving if the space doesn’t feel right.

What do witches do in a coven?

Coven activities vary. Members might:

- Celebrate seasonal sabbats or lunar cycles

- Practice divination, spellwork, or meditation

- Study magical texts or historical witchcraft

- Make art, music, or ritual objects

- Organize activism or community care projects