Happy Equinox! In celebration of the fall equinox, we sat down with Witch/Author Amanda Yates Garcia (Initiated) and Theologian/Author Christena Cleveland (God Is A Black Woman). Together we enter the deep soil to discuss balance - connecting to nature while rebuking colonialism, safety vs risk-taking, being a leader while dismantling hierarchies, navigating our bodies, the land, self and other and belonging, cultivating community while staying true to your own mission. This Mabon, we try to think of ourselves as being in collaboration with our ideas, where the relationship is reciprocal, not transactional.

LISTEN NOW (TRANSCRIPT BELOW)

"Ideas are deceptively powerful."

Christena Cleveland - God Is A Black Woman

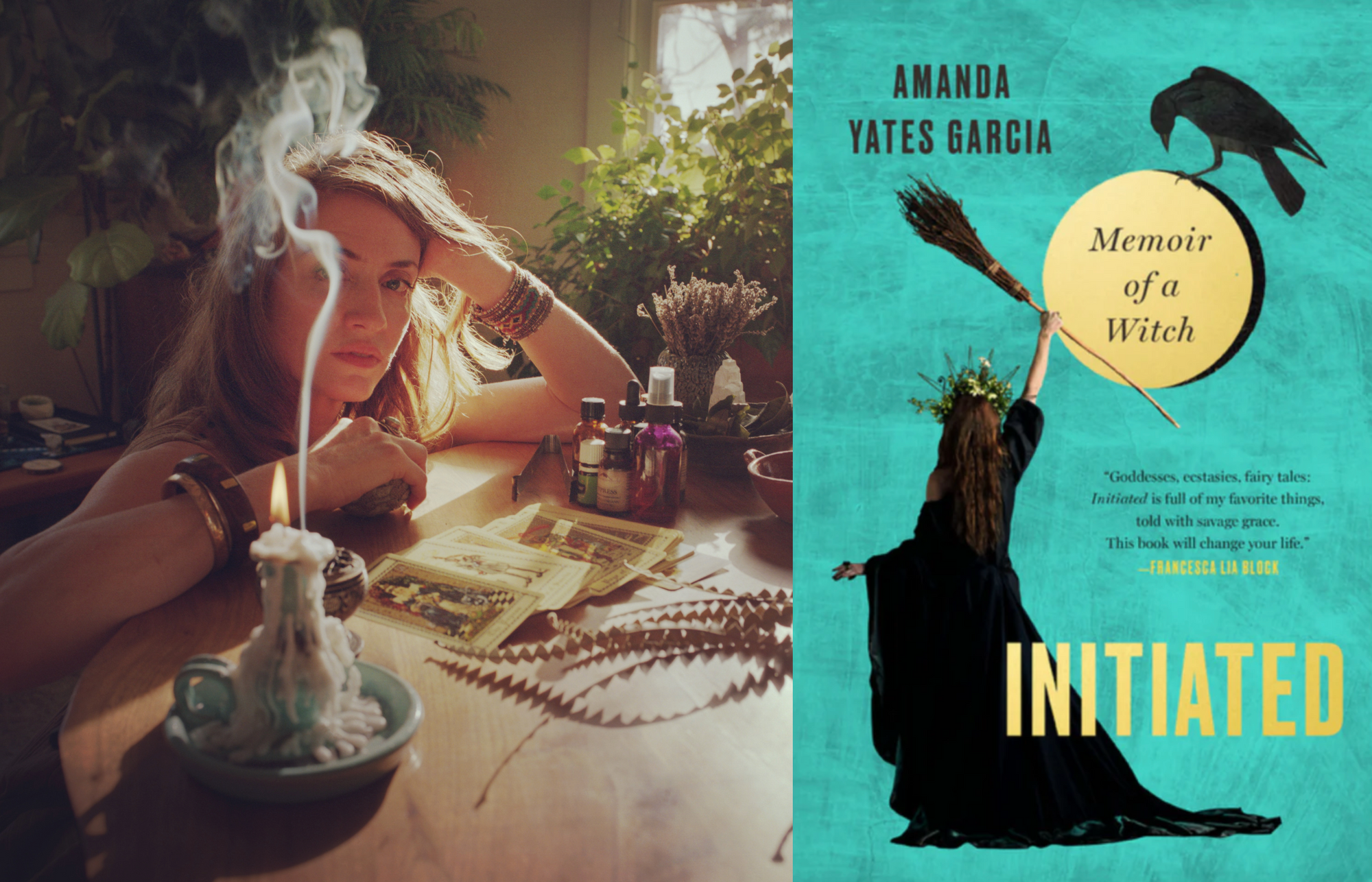

Amanda Yates Garcia

Amanda Yates Garcia is a writer, witch, and the Oracle of Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, The LA Times, The SF Chronicle, The London Times, CNN, BRAVO, as well as a viral appearance on FOX. She has led rituals, classes and workshops on magic and witchcraft at UCLA, UC Irvine, MOCA, The Hammer Museum, LACMA, The Getty and many other venues. Amanda hosts monthly moon rituals online, and the popular Between the Worlds podcast, which looks at the Western Mystery traditions through a mythopoetic lens. Her book, Initiated: Memoir of a Witch, received a starred review from Kirkus and Publisher's Weekly and has been translated into six languages.

Join Amanda's Mystery Cult on Substack

Follow Amanda on Instagram @OracleofLA

Buy Amanda's book Initiated: Memoir of a Witch

Book an appointment with Amanda via her website

Listen to Amanda's podcast Between the Worlds

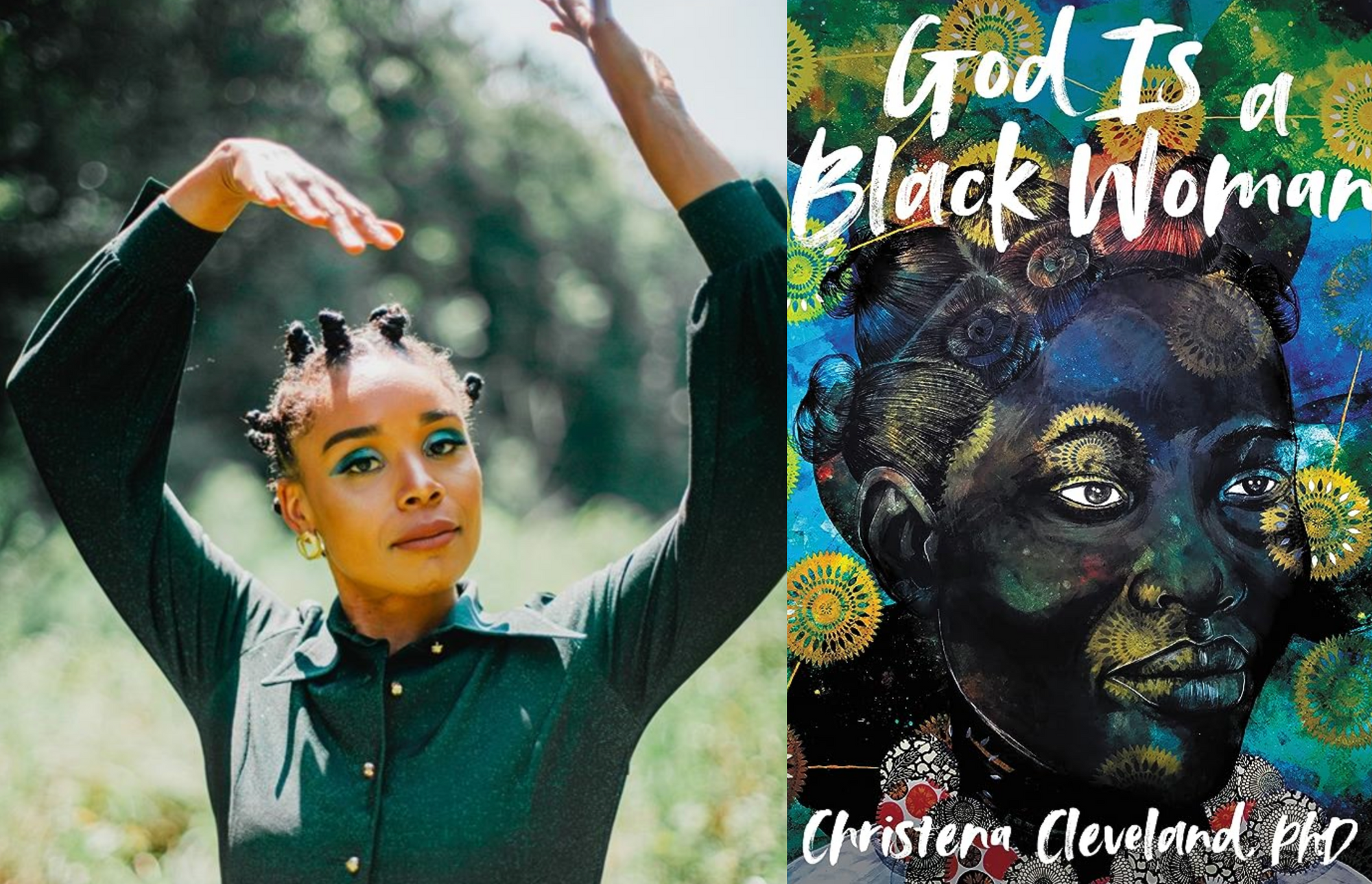

Christena Cleveland

Christena Cleveland, Ph.D. is a social psychologist, public theologian, author, and activist. She is the founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal which supports a more equitable world by nurturing skillful justice advocacy and the depth to act on it.

A weaver at heart, Dr. Cleveland integrates psychology, theology, storytelling, and art to help justice seekers sharpen their understanding of the social realities that maintain injustice while also stimulating the soul’s enormous capacity to resist and transform those realities.

Dr. Cleveland holds a Ph.D. in social psychology from the University of California Santa Barbara, a B.A. from Dartmouth College where she double majored in Sociology and Psychological and Brain Sciences, as well as an honorary doctorate from the Virginia Theological Seminary. An award-winning researcher and author, Christena is a Ford Foundation Fellow who has held faculty positions at several institutions of higher education — most recently at Duke University’s Divinity School, where she was the first African-American and first female director of the Duke Center for Reconciliation, and also led a research team investigating self-compassion as a buffer to racial stress. In 2022, she published her second full-length book, God is a Black Woman (HarperCollins), which details her 400-mile walking pilgrimage across central France in search of ancient Black Madonna statues, and examines the relationship among race, gender, and cultural perceptions of the Divine. Her work has been featured in a number of major media outlets including the History Channel, PBS, Essence Magazine, the Washington Post, NPR, and BBC Radio.

Though Dr. Cleveland loves scholarly inquiry, she is also an avid student of embodied wisdom. She recently completed the Art & Social Change intensive somatic training for millennial leaders, and is currently deepening her mind-body-spirit integration in a year-long embodied leadership cohort for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

A bona fide tea snob, lover of Black art, and Ólafur Arnalds superfan — Christena makes her home in Minneapolis.

"Witchcraft is an act of healing and an act of resistance."

Amanda Yates Garcia - Initiated

TRANSCRIPT:

Mabon 2023

Amy: Happy Mabon! Today marks the five year anniversary of the Missing Witches podcast. Over the past five years, the idea seed has germinated and sprouted and expanded into books, a coven, a zine. If you want to keep the Missing Witches project alive, join our coven. Buy our books, New Moon Magic, 13 Anti Capitalist Tools of Resistance and Re Enchantment.

Amy: Hello! Hi Coven, and welcome to another episode of the Missing Witches podcast. I'm Amy, I'm here with Risa, and our two very, very, very, I'm gonna say very a couple more times, very, very, very special guests who are so near and dear to us. We are thrilled and honoured to have the two of them in our lives. a room together, and we're so excited to see what blooms from this conversation.

Amy: Amanda Yates Garcia, one of our favourite witches in the world. Christina Cleveland, one of our favourite theologians in the world. Let's get together and talk about witchcraft, and God, and ideas, and writing ideas down. Um, so before we dive into our, our equinox, Fantasy. Um, let's start with you, Christina.

Amy: Can you, you've been on the podcast before, obviously. I'm sure most of our listeners are familiar with you and your work. Um, but can you reintroduce yourself? Like, who are you today? Who are you now?

Amy: Oh,

Christena: sure. Um, I'm Christina. I, I don't know if I even want to answer this question today. I'm a learner. I'm a learner of the Black Madonna. And I feel like every day she's teaching me something and it's my life purpose to learn and to listen and then to hopefully communicate and translate her in a way that resonates with people, but specifically black people.

Christena: I'm doing a lot of, um, listening to my ancestor bell hooks. Who said, it's really a shame that African Americans haven't reclaimed the Black Madonna. And I wake up with that quote on my mind most days. So that's who I am today. That's what I'm doing. That's what I'm dreaming about.

Amanda: What a beautiful dream.

Amanda: I'm so excited to be in this dream with you. I hope we don't wake up. Amanda, who are you today? What are you doing? What's going on? Um, yeah, such a big question. Um, and I feel lucky to follow Christina because I was already very inspired by what she had to say there. Um, well, I would say my life's work is really about, um, enchantments, which I understand as, uh, reweaving of webs of connection between the, the self and the, the broader world that have been severed through colonialism and, uh, capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy, et cetera.

Amanda: But I, I don't see those webs as actually having been severed, but more like the settler perception of them or the colonialist perception of them is that they've been severed. And so I see land based Um, spiritual traditions as, as enchanted ones, which are, um, which are woven completely into the matrix of the life force on earth and specifically place.

Amanda: So right now I'm really interested in looking at how, as a, as a settler on land that isn't Quote unquote mine, but that I, that my family has been living on for, um, over seven, seven generations, um, how to have spiritual connection to this place and how to understand my traditions, um, which are Northern European.

Amanda: In theory, but like I said, like my family hasn't lived in Northern Europe for a really long time, so how can I have, um, holidays, spiritual traditions, relationships, um, relationships to the other beings on this land and in this land, um, While at the same time honoring the history of violence that brought us to this place.

Amanda: So, yeah, that's what I'm focused on, but the way that I do that is through, um, I have a newsletter, that sounds so... That sounds so, like, office y or, I don't know, corporate, but um, yeah, I have a newsletter of mystery cults. I have a mystery cult, that sounds better. And um, we do ritual there, and do all this work of enchantment there, and uh, I'm a writer as well.

Amanda: Yeah. I'm

Christena: going to interrupt you and just say, A, I think newsletters are magical. I can't be magical. I can change lives and be, I have a mystery. Cult sounds kind of cult leader ish.

Amanda: I don't know. I don't mind it because I feel like it has kind of a charge to it, you know? And I think, I think of Mr. Colt is like, um, the name of my newsletter is called mystery cult.

Amanda: So, yeah, but, um, but I think of cult, uh, Well, I mean, there's a long story that goes with that. So it's basically that when I was, um, first, when I first got into college, when I was like 18 or 19, and I took this art history class and they were talking about all these like matriarchal goal. You know, Neolithic, um, communities and cultures, and they would talk about, you know, the goddess Inanna, or Ishtar, or Astarte, and they would call them fertility cults, and I would be like, that is so offensive to me, like, that this, that it was like the It was like the dominant religion of the time, and it was called a cult.

Amanda: Why was it called a cult? Like, when, why isn't Christianity called a cult? Or why isn't, you know, Islam called a cult? Or Hinduism called a cult? Because it's like, well, it's given this credibility, so. I feel, um, I'm kind of like reclaiming the world word cult. Mm-hmm. . Um, and yeah, it is a charged word, but I'm also a witch, so I'm used to that

Christena: Uh, well, I can relate. 'cause I, I lived in Taos, New Mexico for most of 2020. In the early part of 2020 we were under lockdown. But then right around, um, Juneteenth in the George Foreman murder, not

Amanda: George Foreman. George Floyd. George Floyd. Is George Foreman like an athlete or something? Yeah, he's a

Christena: boxer.

Christena: And also the George Foreman grill, right? Okay, so thinking of grilling, but anyways, George Floyd. Um, there was this, um, you know, like event that these black trans folks put on around Juneteenth and George Floyd. And so I spoke at it and that was my first like public appearance in Taos. I was brand new. And of course, you know, Taos, which has tons of cults, several cult leaders came up to me after the event or reached out to me and asked for coffee because of course, if you're a cult leader.

Christena: Why wouldn't you want me to be your second in command? You know, like I would be a great assistant cult leader. Um, but after talking with them and sort of like informationally interviewing them, I decided that if I'm going to be in a cold, I would want to leave it. My son was just like, I'm not really like second in command material.

Christena: And it was these interactions with actual cult leaders that helps me see that. I would make a good one myself.

Amanda: I mean, I might join that cult. I would totally come to that cult. But also, I question, like, going back to this idea of, like, what a cult is, I feel like There's so many imbalances of power in any group, you know, in, in most groups of people, like in the government, in major religions, um, in even like political organizations, socialist organizations, like NRA, whatever, like families.

Amanda: Yeah, families. And so the idea, I feel like by saying like, Here's this small group of people and they are a cult, and, and yet here's this other group of people, and they're not a cult, you know? Mm-hmm. , but, but who gets to decide that? And then I also think of the root of the word cult is like in culture or cultivate.

Amanda: Cultivate, yeah. And it's like, for me, it's about nurturing the mystery, growing the mystery, honoring the mystery, um, and also understanding the culture of. Groups of people together, like what happens when groups of people come together and grow things and also thinking of cultures like, um, in, uh, science, right, and biology where you like have a culture and it grows and creates like, um, like bio field, which I like.

Amanda: So, I

Christena: think it was like to, I mean, I think what's so challenging about cults as we, you know, tend to understand them. Is that usually there is a leader and we've associated cultivating with domination. I think in part because of how we've treated the land, but what if we thought about cults as in like, I'm in a mystery permacult.

Christena: I

Amanda: love that. So I'm

Christena: helping what's already there. Flourish. And take root. And I'm

Christena: not trying to control and dominate. I'm just trying to support, you know, but yeah, it's interesting how that's just been turned. Yeah. I took an e course two years ago on spiritual abuse and spiritual power.

Amanda: And it was sounds like a good

Christena: course for spiritual leaders. Because we're who, who led that reclamation collective, which is like, um, led by a group of.

Christena: So, that there are like specifically trained in that. So they create these like processing groups, whether you've been a victim of trauma, which I have been, of course, but also they have processing groups for leaders now, so that those of us who, All we've experienced is toxic leadership in spiritual spaces.

Christena: How do we start to lead differently? And it's like, I lead a work team. I lead a Patreon community. I, you know, there's so many, and then they just define spiritual power as people trust you. So that's like parents. That's teachers, that's therapists, that's the guy on, in the, in the plane next to me who downloads his entire life story on me when I tell him I do whatever, you know what I mean?

Christena: Like sometimes you're not always asking for that power, but it's conferred anyway. And so there was just like 12 weeks, I think of just a bunch of spiritual leaders getting a chance to talk, talk and process and like, what does this look like in my world? Um, but it's like, we need more spaces like that because we have so much power and what does it look like to do it differently and to say.

Christena: Um, yeah, technically, I guess somebody needs to lead or somebody needs to take ownership and responsibility. Um, but everyone has a voice and it's not my way or the highway and I'm like such a Leo that and an enneagram one and the big sister and raised by toxic white patriarchal Christianity. So there's so much divesting.

Christena: That needs to

Amanda: be done. Yeah, and it's really challenging too, because at least in my own practice, like we're all, we're all still living under capitalism, we're all still living under colonialism. So we all still have to like pay our rents and, you know, pay off our student loans and save for retirement and do all of those things and navigating, like having a community.

Amanda: So for instance, like with my You know, subscription service, like, that is my community, it's my responsibility, and the money goes to me as well, because I couldn't do it without the money, like, I wouldn't have the time, it takes a lot of time to cultivate community, like, it's a, it's a job, farming, you know, it's like, it's a job for sure, it's a lot of work, so, so, Navigating those territories of like, well, if the buck does stop with me and like, I have to show up in a certain way and I, um, I have to, uh, like get things done on schedule.

Amanda: Otherwise, I, I don't feel like I feel like I have a responsibility to my people, you know, and simultaneously I feel like my practice and the, the. philosophy of, of witchcraft is, you know, everyone is a priestess, everyone is a priest, everyone is a priest ex, like, there are no spectators in witchcraft, there is no, like, you are your own authority is one of the fundamental tenets of witchcraft, like, you are your own spiritual authority.

Amanda: So that's really important to Um, reemphasize for me and, and simultaneously, I think that we often all like struggle with, like how to, how to do the things that we dream of doing while living in a world that's so challenges and in fact, um, punishes oftentimes people who try and find other ways. Well, this is why I think

Christena: I want to hear so much more about your work with enchantment, particularly with the land.

Christena: Because I, I feel like any of us who are trying to do this revolutionary way of being in this capitalistic world. Um, we, there has to be a deeper resource that we turn to when we're concerned that You know, divesting from hierarchical structures is going to negatively impact our bottom line, and we have a rent to pay.

Christena: And I know, I, I, more, this, just this summer I got connected to this image of the Black Madonna that's called Our Lady of Deep Soil. And I have been, like, rooting in her. And I've been, like, in, um, mining all the different aspects of her death as I've, you know, Gone through a fairly turbulent, like, experience with capitalism this summer and work.

Christena: So I'm really curious to hear, like, how enchantment with the land can nurture the freedom and the liberation to let go when we want to cling. When resource scarcity, which is constantly being programmed into us, is saying cling, cling, cling. Hold on to power. Tell people what to do. Stick to that deadline.

Christena: Don't listen to your body. Don't let people be human, including yourself. Yeah.

Amanda: Well, I feel like ultimately, our fear around our needs being met is one related to belonging. And so the more we connect with the land, which isn't just mean One thing, right? It means that entire matrix, that web of life, meaning humans, pollinators, plants, water.

Amanda: Um, the water table, the way that it connects to the ocean here in L. A. And the, you know, precipitation cycle, all of that is the land. And so the more we reweave these webs of relationship between ourselves and the land, the greater our sense of belonging. And the, the more we'll be able to. I get this image when I think of it as like someone holding on, like gripping to some kind of resource like a nugget of gold or a glass of water or something and it's like we feel like we have to like pry our hands off this resource because we're so terrified of being abandoned and like left to starve and So I was just thinking about this this morning, actually, on my walk, that, like, the land gave me this little bit of wisdom and thinking about specifically because of, um, you know, the school shooting that happened yesterday and, um, the, the recent shootings of people, uh, you know, black people caught targeted or like trans people targeted or, you know, students and I was thinking about the, um, You know, the dominant culture in the United States and how

Amanda: the people who are doing this violence.

Amanda: are so convinced that the only way for them to belong is to shed blood, right? They, they can't even imagine, and I should include myself in this, they can't even imagine a world where they could belong and be safe without killing, exorcising, like, um, extracting other people from the land. It's so tragic for everyone.

Amanda: And yeah, and, and so it really, convinces me that, um, like, we're not going to let that go. We're not going to let that level of violence go unless we feel like we do, like, unless we see there's a possibility that we could belong, like there's a possibility that we could be safe. And that is just this really hard work.

Amanda: Cause even for myself, like I. I panic, you know, like sometimes I really do panic when I'm like, I need to meet this deadline. It feels like a life or death thing, even though like my followers, quote unquote, you know, they're so kind and generous and they're all working on the same stuff too. Like they all believe in taking vial breaks and stuff like that.

Amanda: But nevertheless, I am like, no, I have to, I have to, like, there's a, there's a primal fear in me of not, um, Of not being okay, you know, so I, I feel like for myself, it's about, um, experimentation and seeing like what works for me and then just sharing that with others, but I, I see it's really about connecting with the other beings, like the more I feel connected, the more I feel safe and the more I feel that sense of belonging, the more I feel like, okay, I can take a break and I don't, it's not my job to fix the world, you know, you.

Amanda: How do you, how do you cope with that, Christina? Um, I have a follow up

Christena: question. Okay.

Christena: What you shared is just so beautiful, and it strikes me in light of you having a mystery cult. Because we talked about the trouble with cults, right? Or this idea that they're associated with top down leadership. But usually, cults have a strong sense of belonging. Because of that hierarchical structure.

Christena: So I wonder how do you cultivate belonging, while also resisting what we would sort of stereotypically call old leaders, like vibes.

Amanda: Yeah. Yeah. Before you answer that, Amanda, this, this ties into something I wanted to bring up, so I'm just gonna shoot it out there. Um, that we, we are at the Equinox, and this time makes me think about contradictions, but also balance.

Amanda: And Christina, this is act exactly the point you're making, right? Like, how do we balance leadership with dismantling hierarchy? How do we balance safety with risk taking? Um, Yeah, from an equinox standpoint, maybe. Like thrown in a wild card. Return to the question, but like through the lens of an equinox and, and, and are we seeking a balance?

Amanda: Are we? Just going from, from one side of the binary to the other in the equinox. What do you think?

Christena: Yeah, and just to add more, Amanda, like, I mean, when I think, so, like, groups that have high, what we call, entity in the social psychology world, that's my background, high belonging, high groupishness. They have rules, they have in group, out group lines, they have hierarchy, it's real organized.

Christena: And so, yeah, high control. And so I'm just like, yeah, how do we cultivate belonging when people also have freedom and the boundaries are blurred and there is balance?

Amanda: Yeah, oh my gosh, um, so many, like, uh, paths we could go down as far as, like, what to say about that. First of all, I, I, I just want to say again that when I think of cult, I have many different ideas associated with cult for me, but I, I was thinking of mystery cult in terms of like the mystery cults of like the illusion, the Eleusinian mysteries, or, you know, the mysteries of Dionysus, which, which we don't associate with, with anybody in particular, except for the, the gods themselves, right?

Amanda: Like the Dionysian or the Orphic cults, but those, we are not thinking of, of a specific leader, right? We're thinking more of the mysteries themselves, like a cult in devotion to the mysteries who are the, Cult leaders, we might say, rather than, you know, me in particular, although I think that I am kind of playing with that idea of like cult leader ish, but by, but I was thinking of it as like, kind of more punk rock version initially when I'd, I'd started this project many, many, many, many years ago, this was the first like web domain I ever bought was called Mystery Project, but then when I came back to this, My, um, my podcast producer, Carolyn Pennypacker Riggs and I were saying, I was like saying, well, it could be Mystery Project, but I also kind of was thinking Mystery Cults, and we were like, yeah, that's like the punk rock version.

Amanda: So I was like, let's go with that. It just kind of has more of a like, um, frisson, one might say, but, um, as far as the hierarchies and the belonging and the inside and the outside. I would say, first of all, I like to look to, um, other animals besides humans, like wolf packs also have a really strong sense of belonging, that like all, all animals, like elephants have a strong sense of belonging.

Amanda: Um, orcas have a strong sense of belonging. Lots of mammals that live in groups have strong senses of belonging. And, um, from a kind of more anarchistic perspective, I think groups have to determine what works for them. Rather than, like, this is the way we do it, and so that this is the way everyone should do it.

Amanda: Like, I can say in my group, right now, it's working to do the work that we're doing in the way that it's happening. But, I mean, groups evolve. Eventually, maybe one day I'll step back from a leadership position once it's more established, or, you know, I've figured out a way to do that. Um... So it seems like the group norms and dynamics and who's inside and who's outside, um, would have to be determined, like, as a self organizing system by the group itself.

Amanda: What, what do you, what comes up for you?

Amanda: Well, I,

Christena: you know, I feel like I personally am a bit of a refugee from, from groups, specifically spiritual groups. And I think a lot of people in my crowd relate to that. Like we care deeply about our spirituality. We want to do it in community, but our experiences have been entirely toxic. Um, and so we're trying to dream up what that looks like.

Christena: Um, and I'll say personally. Um, fits and starts like real clunky, real patriarchal. I'll give you an example from this spring, you know, so I, I do a lot of work around the black Madonna. Um, I was when I first found the black Madonna like eight years ago or whatever, like right in the heart of my leaving, like sort of Orthodox Christianity.

Christena: Um, I felt so, I finally felt like I belonged to her at least. Right. But then. I met the Black Medonic community, which is white women, and it was like, extra painful to not to be excluded from that community, and it was like, almost unbearable, you know what I mean? Because I had finally found, and so I wanted to cling to her because I'm like, this is the one place in the world where I belong.

Christena: And there's like a lot of other people telling me I don't belong. So then I reacted, I had, I think like kind of what you described earlier with this, like, um, like panic, you know, like where, what, so then I kind of went into this, like. White women are the worst, which is, like, true a lot of the time, so I'm not, you know what I mean, like, I'm not saying, like, you know, it was completely inaccurate, but it was, it was too much, right?

Christena: It was reactive. Just for podcast

Amanda: listeners who can't see us, the three white women directly in front of Christina all giggled and nodded when she said white women are sometimes slash often the worst.

Christena: We all, we're all on board for that characterization. Right. I don't belong. You've done it. Yeah.

Amanda: Just so listeners know we're here with you.

Christena: Okay, yeah. Um, and so then my response to that was like, I'm going to create a black Madonna that's not for white women and dah, dah, dah, dah. And so that's my way of creating community, right? And excluding them because I couldn't control them. And I remember this spring having, I went, I taught this terrible e course on the Black Madonna that was mostly populated by white women.

Christena: And there was like a gang of white women. Some, some of them are actually quite noted teachers of the Black Madonna worldwide who joined the e course just to like, undermine me and would undermine me every single week in the e course in the comments. I actually saved some of the comments because I'll be using those.

Christena: I mean, I think a public, a comment in an e course like that in Zoom is public. You know what I mean? I will be sharing but, um, I just remember after one of the course class session being so angry and going upstairs to, I was living in, um, the Boston area at the time and going upstairs to my loft where I had tons of black Madonna's surrounded by them and screaming and being like, these white women, because I didn't feel like I belonged.

Christena: And I feel like the black Madonna just said to me, like, I just dropped my knees and started crying because I feel like she said, Christina, they don't own me. And neither do you.

Christena: And even now, like, I feel so emotional even saying that because I think it is so human, especially those of us who've been so shaped by colonialism to say, I have to possess in order to feel safe. And that's what community is, possession. And I'm still wrestling with like, what does it even look like to like be I'm for black people connecting with the black Madonna.

Christena: And also, I'm not against whatever is happening around the black Madonna, because, like, you know, so it's just this like ongoing, I guess invitation for me to release and to just stop clinging. But it feels like a huge sacrifice and it feels like a huge, um, purification process. You know, like, who is the Black Madonna to me if she's more than just something to make me feel like I belong?

Christena: I

Amanda: mean, first of all, I'm so sorry that that happened. It's like... Just the, the pain, hearing the pain in your voice when you talk about that is really, like, I really feel it, you know, feels like I can feel like getting choked up or like the idea that there's this like precious thing that finally you found and that it's been like taken by the very people who've like taken everything like historically.

Amanda: Um, yeah. Uh, and I so am resonating with what you're saying about

Amanda: colonialism, and I was thinking that actually kind of making that connection while you're speaking, obviously from kind of the other side of the fence, right, as like people whose, whose family were colonizers. And continue to colonize, um, and I think it goes back to this idea that, like, colon colonialism, like, is this corrupting force that affects both ways, like, because just thinking about, like, in my own family, for instance, um, it's done so much damage, like, the violence within my own family, as we were kind of speaking to before we even got on the line, um, um, Is, is a result of colonialism and, and, and how it affects the family unit.

Amanda: And so, like, it goes back to what we were saying about how it's like, we can't even imagine a way of doing it, a way of being in community or a way of belonging that doesn't involve ownership in some way. It all comes down to that ultimately, like we, we don't even remember that there could maybe there could in some universe be some other way of doing this, we were saying to also reminded me of, um, some of the work of bio Akuma Lafayette, who talks about he was talking about that idea of a Shay, which is, um, I'm not sure, is it a Yoruban word, which kind of is like a spiritual force of the universe.

Amanda: Yeah. And someone was asking him about, like, does he get mad when white people say the word Ashe? You know, white people love to say Ashe and Aho and like all sorts of like indigenous kind of words, um, in their spiritual gatherings. And he was saying that it doesn't because He is like the, because it's a colonialist idea that we can own of spiritual force because we think it's like our idea, but the, but in fact it's its own thing.

Amanda: It's its own power. We don't get to say what it does or where it comes or where it goes. And he talks about the idea of Asche is like when somebody says Asche that, that, that the force of Asche like comes into the room. And manifest itself there and that that it had some kind of agency or volition and bringing itself into that space.

Amanda: I'm making the connection now between that and like, for instance, like plant medicines like ayahuasca or mushrooms and how like, I do believe that the plants. Are like trying to get through to us, right? They're trying to be like, look, there's this other way. Look at the plants. Like, look at the way plants live together.

Amanda: We can do this together, people. But that doesn't mean that people always get it right because people go to like ayahuasca tourism and like just practice like colonizing like the Amazon. But that doesn't mean that the message is wrong. It just means we're still confused. You know,

Amanda: I want to pick this word out of, um, ideas, um, not owning ideas, but also like both of you are authors. So part of you must feel like, you know, this is my idea and I need to write it down. And I need to share it maybe I'll read something from Christina and Amanda maybe you can react to it and then I'll read something from Amanda's book and maybe Christine can react to it.

Amanda: Um, we'll start with God is a black woman. This notion of ideas. Christina wrote, Let's pull back for a minute to study the idea of God. If you close your eyes and try to imagine God, what image comes to mind? Even if we don't call ourselves spiritual or religious, gods matter because ideas matter. Ideas are deceptively powerful.

Amanda: Even when we barely pay them any conscious attention, ideas have the power to change our emotions, thoughts. and behaviors. Amanda, do you want to talk a little bit more about the power of ideas? I wonder if

Amanda: there's some way in which we collaborate with ideas in a group way, because I'm thinking of, as Christina was speaking about the idea of God, And, um, I see paganism or animist tradition, so like paganism being like a European form of animist, I mean, it's like a broad word, but let's say animist traditions.

Amanda: The idea of what God is is so different in that kind of worldview and that ontology. So I see the idea of God or the gods as like this collaborative project that involves like a mythopoetics, right? So there's like myths that are part of plants. Ideas that are part of plants, but we eat the plants, the plants are part of us, you know, our bones go into the earth that we are part of the earth.

Amanda: And so there's this way that there's like collaborative ideas and, um, there, but that if I'm understanding correctly, one of the things that Christina seems to be isolating in that passage is like the. The sort of non corporeal or the imaginative, the imaginal part of ideas that are like, you know, they can switch, they can change, we can't pin them down exactly, they can come up as symbols, they can be represented in multiple different ways, um, and that they are very powerful even though they may be not.

Amanda: material in the sense that we like normally think of material objects. Um,

Amanda: we might even, if I'm understanding it correctly, I'm kind of understanding in the same way as like an archetype, which is like a force that kind of is like a paradigm that things shape themselves into. Um,

Amanda: I think it really relates to what we're saying now about this imagining of a kind of belonging that doesn't know ownership. And, um, therefore, If we can imagine it, which is like what an idea is, then it can, it can happen. Isn't it somebody, is it Tony K. Bambara? I know Adrienne Marie Brown talks about this, like that, that like we have to, we have to be able to imagine this other way of living and that that's why artists are so important.

Amanda: Because without, like, artists are the people whose jobs are to imagine things that haven't yet occurred or that are outside of the dominant order. So, I guess I say yes. I say yes to that passage. I cheer on that passage. I just want to add, like, um, part of why I connect so much with both your work is that a lot of spiritual work can avoid the political.

Amanda: And, uh, you know, in the worst case form, it's like groups where it's like, we don't talk politics here, or actually it can be a lot worse than that. But that, that can be really, um, disempowering and infuriating. Um, I want my magic. I want my re enchantment to fuel actual. Equality. I want, I want physical, social change.

Amanda: I want housing for all. I want, you know, like, I want fucking healthcare for Americans. Like, I want that stuff baked into my, my life, my work all the time. Um, and I think those are ideas that are. You know, begin maybe a symbolic action as, as Deb pointed out in the chat and that Rebecca Solnit says, you know, all revolutions start with symbolic action that comes from a place of art and then it can become direct action and then and more.

Amanda: And so I'm so drawn to the way both of you practice and talk because deeply rooted in that feeling of searching for belonging and of spirituality is a real honest negotiation with the shit that is broken. And with bringing community together around activism, I wondered if Christina, I, I know you directly take on the idea of anti capitalism and it's a point of connection.

Amanda: I know you wrote back to us when you saw the title of our book had anti capitalism in it, I felt proud that you felt proud of us. Yes, let's talk about it. Let's put it right in the title. Um, I wondered if you could draw that into this conversation and the way you write about ideas and the power of ideas.

Amanda: Yeah, I was just that's such a,

Christena: um, useful addition because I was thinking about what Amanda just said about ayahuasca and people going and like consuming to like sort of tourist, touristic consuming of it. And it kind of points me back again to like our idea, even our ideas about God. Right. And so like, I know, yeah.

Christena: Because I was discipled into a religion with a God that was like a victor and like a go forth and taker and a top down authoritarian. Of course, my first steps towards the Black Madonna are that because that's what it means to be faithful. That's what little Christina was taught. You know, in Sunday school, when she learned that, that, that Yahweh told all of the, you know, freed, enslaved people, the Hebrews to go and like commit genocide and kill all the black and brown people who worship the black and brown goddess, you know, like, that's literally what it means to be free, to be a follower, to be righteous.

Christena: And so of course, when people get connected to a spiritual resource. Like ayahuasca, it's going to be, well, yeah, claim it. That's what it means to be free. That's what it means to be righteous. Um, and I think because so much of our ideas of God are tied up in capitalism. And, um, I used to, I used to write a lot about capitalism in Christianity.

Christena: This was years ago. And I remember once writing that we think that financial independence is a fruit of the spirit. Like it's proof that you're like a better Christian than other people, because you don't, you're not poor, you don't have need, you don't have to go to the church and ask for canned goods.

Christena: And so like, I was just talking about how, like in a lot of middle class churches, poor people are never elders. You can, you can't be needing the church's help and also a leader in the church at the same time. And that connection between, you know, like. Winning at capitalism and God is just so powerful in the American psyche.

Christena: Um, and it's why we believe that, you know, if you don't have your own money, why should you have healthcare? Like you're not, you're not even human. You literally are not even human. So why? So of course we're not going to have universal healthcare because some people don't deserve it according to our concept of God.

Christena: Which is a very much like, um, you know, like godliness is cleanliness is next to godliness kind of idea, you know, so, um, Risa, I don't know if that speaks to what you were talking about at all, but that's the beginning of it, and that's why I was, I was really excited to read your book and to even have like a little tiny, like, shout out, because, um, we need ways to, we need more ways To identify how to get free of it's just deep.

Christena: It's just so deeply baked into our psyche. Um, and I was going back to the partisan work ethic too. And just this idea that like, to work yourself to death is like the holiest thing you can do other than go become a priest. That's like literally how it got started. Not everybody can be a priest. So here's how you can be a priest in the world.

Christena: Work hard. Kill yourself. Yeah. You know, so it's just There's so much to unpack

Amanda: there. Yeah.

Amanda: Let's go to a reading from Initiated and Christine, you can tell me what, you can give your, uh, your review.

Amanda: This is from Initiated by Amanda Yates Garcia. Witchcraft is an act of healing and an act of resistance. Declaring oneself a witch, practicing magic, has everything to do with claiming authority and power for oneself. Life itself initiates each of us according to our own particular stories. Our stories lead us toward our purpose in this world.

Amanda: Each initiation strips away something and gives us a gift. If we want to meet our full form, we are obligated to give that gift to the world. And Christina, maybe if you could focus on this notion of like, if you're given a gift, or if you're given an idea, that you're obligated to share it. Again, both of you are...

Amanda: Our authors, both of you have, um, websites, newsletters, you know, projects that are continuing and going. What do you think about this, this, uh, maybe to, to, to use a Christian term of phrase, like evangelizing your ideas. What

Christena: do we think about that? Like a calling to share. Yeah. What do we think about that?

Christena: Okay. First of all, what a beautiful, um, passage you just read. Thank you, Amy, for reading it. Thank you, Amanda, for writing it. Um, wow, it sounds like, to me, that whole passage just sounds like major soul deconstruction. Like, um, identity liberation, you know, like, I'm no longer going to let the world determine If I do or do not have power, I'm going to claim it for myself.

Christena: And I liked that it was for myself, not over myself or against myself, which I think is a common trend in my life. Um, that idea, the idea of an obligation to share it with the world, just for my, it reminds me of Harriet Tubman. It was like, if you get free, go back and get other people free. And I, I really intentionally want to take it back to that because I feel like in this case, that idea is an action.

Christena: It's not, uh, an ownership thing. Like she, she couldn't, she couldn't own more people by setting them free. If anything, it was hurting her bottom line to set, to go back and set people free. But I think she felt like a righteous obligation, like, how can I be out here being free if other people are not free?

Christena: Um, and of course, like Danny Lou Hamer said the same thing, like, if none of us, if all of us aren't free, then none of us are free. Um, and so to me, that's where the, I think we're obligated to share this with the world, that even ideas, um, feels really resonant. But in that sense to me, it, yeah, obligation is such a tough word for me, um, just with my background.

Christena: Um, it's, it's like should, I actually just recently told a beloved in my life, like, just don't use that word with me because I just, I don't like it. And obligation, I'm like, even in the moment I'm trying to unpack, like, what really is obligation and does it have to be this authoritarian thing? Can it be more of like a devotion?

Christena: Because I'm just noticing that I have baggage with that word, um, where I don't feel like anyone's forcing me. It's more of like an invitation that if I really want to be free, if I really want to experience my power, the best way to do that is to be really intentional about sharing it. Yeah, maybe obligation is like a secret.

Christena: Here's the secret pathway.

Amanda: I, I think, I think in the, in this passage, I sort of, um, interpret obligation more like you would say to someone who's done you a favor. Oh, much obliged, you know, like you

Christena: have given me something. I mean, do people say that in the US? Um,

Amanda: maybe not. I'm kind of an old soul. I feel like that's from like, 2000

Christena: or something.

Christena: Oh, much obliged. yeah, I was just like, do people say that? No,

Amanda: nobody says it but me. But when I say it, what I mean is, not a sense of like, well now I'm weighted down by, you know, the duty that I have to, but more like, You've done me a favor and I am much obliged to you. And however, I can like pay it back to the universe is, is what I want to do.

Amanda: Amanda, does that make sense to you being much obliged? Yeah. Um, you know, I, the, the word obliged does have a lot of, um, It has like a lot of history. If I were to rewrite that, I don't know if I would use that word still though. I might, but, um, yeah, I think the way that I was thinking of that was more of like, as, um, like if we imagine a gift economy, that the wealth of the community comes through the trust that resources are shared.

Amanda: So wealth comes through the movement of. Resource the, the blood of resource through the body, whereas in our culture, in the dominant culture, wealth is like essentially the hoarding of resources. And we might think of that in relation to ideas as like. This is my idea and if you're going to use it, then, you know, we need to copyright it and we need to like, I need to be getting the, um, what's it called when you get like money from royalties, royalties.

Amanda: Yeah, I need to be getting the royalties. And it's like, yeah, like the writers right now in Hollywood are fighting for that because like they do need that in order to survive in our world. And I can also imagine a world where we don't have to worry about that. Because the ideas are flowing as, um, as Christina was talking about in that her own beautiful passage about like ideas being very powerful and, and therefore they shouldn't just be hoarded to oneself, but they need to be allowed to percolate through the community and, um, and that that is the way that real.

Amanda: and security happens is when those ideas go forth. However, it comes back always to this thing that we're talking about, about like wrestling with that on, um, on a daily basis, like within our own lives as writers. Like, yes, of course I don't want somebody to just copy my book and then like go out and make money of it because then it's like, yeah, my, my, that will impact my.

Amanda: You know, tenuous middle class lifestyle or whatever. I might, you know, it feels threatening. So, and, and that's legitimate. On the other hand. In an ideal way. I don't want to do that. And I want to be like, yeah, take it. See what you can do with it. Like what happens next? Um, so, yeah, I don't know how, how to do that, but I'm trying to figure it out in my daily life.

Amanda: Yeah, I think it's like

Christena: what Oh, sorry. No, you go ahead. Oh, okay. Well, I, to me, it just, I feel like what Amanda you've been sharing about obliged or just like much obliged. Yeah. Makes me think of like tag. I'm and that I'm being invited into a reciprocal relationship, not like a transactional relationship.

Christena: But I mean, I was talking with a friend, one of my best friends. We've been friends since my first year in college. So over 2020, almost 25 years now. Um, and she, she and I were talking about what is friendship even mean today. And they're just noticing that over the course of our lives, a lot of what we called friendship was really obligation.

Christena: Or, um, something that was really lopsided, you know, and how we talked about now, like friendship, whatever friendship is, it's the one thing that needs to be there as a mutuality in order for it to be, to feel like friendship. Um, and I think that kind of going back to Equinox balance, um, this idea that. We see, can you tell I was a professor for a long time?

Christena: Um, but anyways, this idea that, you know. This all works in balance. So yeah, I give and you give, um, and without keeping tabs, but just with also, I mean, I think intimate relationships that work well, there is a general sense of balance, right? Like you're not necessarily keeping tabs, but you're also generally aware that There's some, oh, there's a little bit of imbalance here.

Christena: Let's adjust that, um, so that there's, there's balance. And so, um, yeah, I just, I, that's just, those resonate with me. But I also just, what's coming to mind too is also history. And the history of silencing, stealing of stories, profiting off of people's work, particularly women, particularly people of color, particularly, you know, you know, queer folks.

Christena: And, um, and so to me, it resonates. What you said, Amanda, about like, you know, I have this tenuous middle class life. So no, I don't want you, I don't necessarily want to copyright everything I do, but I also don't want you just running off. And that's why I feel like the enchantment that you're talking about in your book, even in that little passage is an invitation into this mystical reality, right?

Christena: There's this, there's this grounded reality of like. Yeah, please don't steal my work because that actually impacts me in a really negative way. But then there's also like a mystical reality we're being invited into that I think like the Black Madonna is inviting me into of like, and also, I got you. The more power you give away, the more you'll have.

Christena: Like it's this, and I can't describe it. I just know it's there. It's there.

Amanda: I feel like you just described it really well. But, but what you're saying, um, and what you're saying really resonates with me in relation to the Equinox as well. Um, I was thinking about Mabon, which is the name of the holiday for witches, and, um, that name comes from Mabon at Mabon, who's a god, a Welsh god, and the name means divine son, but he's also kind of a trans god, I see him as kind of a transitional god because he's about like the shifting between seasons.

Amanda: And so that's like literally a transitive function, like in his, um, kind of spirit is iconography. But, um, what I think about that is that. If we think the divine sun often relates to literally the sun in our solar system and for which is the this winter solstice is like the darkest night of the year and as my mother says.

Amanda: about that holiday. It's when, it's only during the night when it's dark that you can see out into the limitless universe. When the sun is shining, we can just see what's around us. And so for, for witches, there's this idea of like the ego, the solar eye, the self, and it's very bright and luminous. There's a lot of beauty to it.

Amanda: But when it's gone, when it's on the other side of the earth and we can't see it, that's when we can see out into the communal, which in a way is more powerful because it's infinite, right? It's the entirety of all being that we can't even see the end of. So there's these, this balance of forces of like the self who's like wrestling with the truth of material existence.

Amanda: And then there's that mystical force that you were just talking about, Christina, which is like, yes. And the infinite, the, the, the thing with no beginning, no end, no, I no division, no separation, and that they're intertwined, they're simultaneous with one another, and that's what kind of happens in this specific holiday, is that like we're celebrating and all honoring that, and then for me what I really love too is that this holiday is the second harvest holiday.

Amanda: The first one being Lunasa, which is the harvest of the first fruits, um, at August 1st. And the third being Samhain, which is an honoring an ancestral holiday and celebration of the, um, you know, the spirits of the beyond. But so here we are in the middle, and this is really about like gratitude and feasting and abundance.

Amanda: And so I think it kind of comes back to what we're saying, that like true abundance. Limitless abundance. Renew, like, abundance that renews and renews and renews and renews has to do with this, this ebb and flow of seasons, tides, money, ideas, um, like, self and other. And, and that's just what I love about witchcraft and paganism is like, we have a holiday that is about this, like that you're supposed to think about this and like honor it and do something, um, in your community that, um, that really makes these ideas real for you.

Amanda: I'm really curious about how the. In the cult of the Black Madonna, if I can say that, um, how, how do y'all deal with the Equinox, the Autumn Equinox? What's your celebratory style here? I don't have one,

Christena: personally. Yeah, I'd be curious to know what other people who are devoted to the Black Madonna do. I know that there are a lot of people who are devoted to Black Madonna who would also identify as like Wiccan or something, and so they would probably, um, commemorate the equinox similarly to you, but um, I do, I mean, one of the things that I love about the Black Madonna is that she's so many things all at once, and she's Constantly inviting me into yes and ness a whole lot more.

Christena: Yeah. And so that looks like, oh, sometimes that can be painful because I want to say no. But

Amanda: yeah, I wonder what the black Madonna. I don't know this, but I'm wondering if you know, like, She's making me think of, uh, Nuit, you know, the goddess of the night sky in Egyptian lore, and then like connecting that like to the winter solstice, like that, like that totality of being that endless, like a soup of the cosmic that from which everything comes.

Christena: Yeah, and Clark Strand, who's a writer, uh, a writer and devotee of the Black Madonna, talks a lot about the Black Madonna, um, as the darkest part of the night, as like the infinite darkness, which gets tricky when you're talking about blackness and darkness, and he's writing as a white man too, so it's complicated.

Christena: But one of the things that I like that he says is that, you know, he discovered one night commuting with the darkness under that the darkness is not a what it's a who, and that there's this invitation into intimacy. That can only happen as we move into as, as we move into what I would call like womb spaces, uncertainty spaces like incubation spaces as opposed to darkness, which is usually equated with bad and black.

Christena: And so, but this idea that you know this uncertainty space. This infinite night that perhaps night of the soul is an invitation into. Being nurtured, cultivated, um, dependent, and, and so, so to me, that's like a really disruptive way of thinking about balance too, because of course, I've been, you know, as a, as a capitalist and as someone who was raised, um, in Christianity, of course, the sun is goodness and light is right.

Christena: And so that, like,

Christena: not just accepting or making peace. With the uncertainty but also cherishing it and seeing it as a who that wants to be known by me and a who that is ultimately trustworthy, even if I don't get it. Um, and even if that who doesn't feel safe, necessarily, um, that to me feels like just. a love letter.

Christena: And I think, you know, this morning I was just in my own practice, because I've been sitting in front of this image of Our Lady of Deep Soil every day for, I don't know, maybe the last 60 days or so, and I'm always just trying to get more connected to this image, and I was just imagining myself being an earthworm, spelunking the deep soil, you know, and gosh, what, how to be surrounded by that much blackness, that much Um, that I can't see the unknown and everywhere I turn there's more of it and, um, maybe there's, it doesn't feel like there's a way out or back to the surface anytime soon.

Christena: And, like, I've been spelunking and, um, I definitely had like probably a panic attack, you know, cause I just didn't like, I didn't like that feeling. I didn't like it. And I was flunking with like three super skinny white guys who did not have butts or hips. And they'd be like, come on, we're just going to go through this little hole.

Christena: And I'm like, my bus is not going to make it. It's not like,

Christena: I'm going to be stuck here. Like, so I was trying to just connect with that feeling and then, oh, but this is deep soil and this soil is good. And this soil, I can actually just like stop panicking and breathe

Christena: because she's not going to let me get lost in here. And this is an invitation to this like adventure. I like the

Amanda: earthworm image because like earthworms, of course, move the soil through their body like, like they're part of it, right? I didn't know that. Yeah, like if you, if you cut an earthworm in half, there's like dirt inside of it.

Amanda: Like they eat the dirt essentially. And then they like through their digestive juices, like, um, essentially inoculate it with like even more nourishment. Taking notes. But, um, I'm also thinking about. Going back to this idea of colonialism and, and that kind of concept of ownership and how often I've been so deeply troubled by this binarism in our culture that like black.

Amanda: Night and like black people, like, like black people get the night and white people get the light and the day and house, like how completely stupid and arbitrary that is like, why do like the idea of owning something like light or owning something like darkness or being like, this goes with them and this goes with like, it's such a weird idea, like that sunlight.

Amanda: Gets correlated with essentially like skin color of like one little animal on this earth that has only existed for a couple hundred thousand years in this like billions of years old solar system and also thinking about how like so many African traditions like are about light and like have whole whales You know, um, religious traditions that are like really located in the light, like Egyptian, you know, solar gods or whatever, like, it's just such a strange arbitrary idea that like light equals essentially like pink people and also

Christena: like gender too, like, masculinity.

Christena: And darkness and the moon are associated with femininity. And actually, you know, what's interesting is there are a good number there's, you know, there's all these like weird reasons, like complex reasons why the black Madonna is black. And there are all these like explanations. Um, but some black Madonna's are black as activist art.

Christena: They became black in response to the Renaissance because artists were like, you can't say that everything good is male and, and white and light. And so they went, and so you see these Black, so some Black, you know, you see these Black Madonnas, and you look at them and you're like, you kind of just look like a white lady and Black face, you know, because literally they were just painted over.

Christena: Like, I'm like, you don't even, like, it's like. Um, I guess that that is a simplistic way of looking at it too, because it could be that they're like me and they're 23 percent white, which I recently learned in AncestryDNA and was like kind of horri it was, it was, there was, I had an identity crisis, let's just say that.

Christena: Um, but you know, it could be that too, but, um, but this, this resistance to that very idea that you're talking about, but, you know, happening in the 17, 16, 17 centuries where activists were just like, no, we don't accept that. I just

Amanda: wondered though if Oh, sorry. I just want to add quickly, play with the earthworm metaphor and idea that Majority of earthworms in North America are not indigenous.

Amanda: That I know. They're also brought here. You know, there were almost no earthworms here like 10, 000 years ago after the Ice Ages. They were almost all brought here in the 1800s by settler colonizers. And so the majority of our land is, and sometimes they're fueling the land and sometimes they're not.

Amanda: Sometimes they're, they're straight up stripping the soil. And it's so interesting to me to like, Dig deeper into the history of those kinship relationships, right? Because it helps me understand myself. Like who was, who was also brought here? Who is doing harm without realizing it? How do we relate to those?

Amanda: If I can have empathy and care for, you know, a species gone wild in my garden, can I have empathy and care and also try to Do better. And I wanted to add also, I think a lot about the darkness in a universal sense, uh, you know, that we're the majority of the universe is dark matter. And we haven't figured it out because we haven't been able to stop paying attention to the, the tiny bright objects that are actually such a small portion of what it all is.

Amanda: You know, we haven't understood dark matter yet at all because we haven't. Even known how to look at it. So I wanted to just add those two pieces with love. Wow. The

Christena: earthworms are out here just being colonial settlers.

Amanda: But

Christena: that speaks to me so much to what Amanda, you were saying about a resource that's renewable, that we're feeding off that, that's something that.

Amanda: For me, all of this goes back to another thread about this conversation, which is we don't know what the fuck is going on, right? Like we're so small and Like, we can think, like, you know, here's this idea of the Madonna, and of course the Madonna was taken from like, Astarte and Ishar, and all these other goddesses, and then kind of became this other thing, and then artists in the Renaissance painted her black, or whatever.

Amanda: But we don't know that that's not the Madonna, or whatever force that is that's like, I, you, you can't get rid of me, like, I'll be here. I'm going to come back and come back and come back in some form and you're going to try and get rid of me. You're going to try and get rid of the Madonna even. And then she'll come back and she'll come back and she'll come back because that's like she's bigger than us.

Amanda: We're not in control here. Similarly, I'm thinking about like invasive species and how, you know, yeah, they are colonizers. They were brought by colonizers. They're very destructive. You know, they can erode forests and, and like a couple of generations. On the other hand, we don't know. what is really happening, right?

Amanda: Because when we think of invasive species, like a lot of people like cut down the weeds that are like growing in the abandoned parking lot. And yet that, that, those weeds are the only ones that can live there. And they're the ones who are like remediating that soil. And we as humans are like, no, I know better what should be done here.

Amanda: And like that we shouldn't be there. It's not even, it doesn't even belong on this continent, but you know, there's this, there's this great book called beyond the war on invasive species. It's a scientist who was like, all about remediating soil and like dealing with invasive plants and stuff. And he was talking about how he had been hired to like regenerate this kind of swampy land that had, um, been overrun with this invasive species.

Amanda: And he was trying to rehabilitate it so that, um, the indigenous species could live there and thrive there. But the land over so many generations had been so. Fucked with that, the indigenous species really couldn't live there anymore. And yeah, these invasive species could live there and that they were like changing the soil in such a way that like other beings could, could live there again.

Amanda: And I think about that garbage patch at the center of the Pacific ocean. That's like the size of Texas and what a great tragedy. Right. But then. I mean, I cry about it all the time. This stuff is devastating to me. I'm on antidepressants because I can't handle the way that like the world is, you know, dealing with all this violence.

Amanda: But, um, but like there are microbes on that plastic that are like, we can live here. We can break this down. It might take us like a million years, but like the goddess, as I understand her, potentially the black Madonna is like, she just knows what to put there and it'll go there, like maybe not within our lifespan.

Amanda: I, I, I studied with the Zen Roshi, this, um, Daito lori, uh, in the Zen monastery when I was like in my late twenties, and I can't remember the context of why I asked this question, but I was just like, I was just, I was upset that. Like, people were suffering, essentially, and he had given this reason, and I wasn't satisfied with it, and I was like, well, how, why is there colonialism still, like, in Africa then, and, like, all these people are suffering there, and tortured, and, like, like, wealth is extracted from them, and it's so unfair, and he was like, well, yeah, but you don't know the end of the story yet, like, you don't know what happens, Because many civilizations have risen and fallen, maybe in a thousand years, like, the, the tables have turned, or have gone into something completely different.

Amanda: Like, we, we see from the perspective of now, we see from a human perspective, but we don't, we can't see from that universal perspective where the story just keeps going and going, and it won't be the way that it is forever. I don't know if that resonates for anyone, but my point with that is totally resonates

Christena: with me.

Christena: Yeah. The humility, right. Of just recognizing too, that like, not only are, um, you know, humans just this like speck in the history of the world. Like I'm, so am I, you know, and it's, and I think that totally resonates too with the goddess slash black Madonna. Cause I, as much as I love to talk about the black Madonna, you know, um,

Christena: Magnanimous love and abundance and, you know, the life spring and the renewable resource that she is. I also call her Our Lady of Fuck Around and Find Out. Because, like, there are some stories about the Black Madonna where I'm like, Yeah, she's not playing, you know. And there's a pettiness to her, too. But the best kind of pettiness.

Christena: The kind of pettiness that... Has a holy no underneath it. And so if you actually listen. You're going to learn something, you're going to get some wisdom from that petty bitch, you know, but it's interesting when you see like these, these goddess stories where they come back and it's like, Whoa, they escalated it.

Christena: You know what I mean? Like, that was not a proportional response.

Christena: Like the Artemis stories or whatever I did this being called writing with Artemis last fall where every, every month. Every week I drove up into Vermont and did trail running and listen to Artemis stories from the Switch and we like integrated it. And so I've, I just heard so many Artemis stories this time last year.

Christena: I was like,

Amanda: Right. She's like, you catch me bathing. I'm going to like sick these wild dogs on you to tear out your entrails.

Christena: Yeah. And I have a whole pack of like dog

Amanda: gnomes,

Christena: like fairies, like a bunch of people. I have a whole army of mythical creatures that will come for you. If you look at me the wrong way, if you look at me with lust, you know what I mean?

Christena: So there's that element too, of just like. And that's, it's funny 'cause uh, in 20 20 10, yeah. I was doing this gender and Christianity seminar like month long fellowship thing. And I met this woman who's really high up in the, um, Catholic church. She's like a, um, a provost at one of the like, major Catholic universities.

Christena: And I just remember talking to her and, and she's a feminist, you know, and intersectional feminist. I was like, how do you even deal with being in this, like, you're, you, you're so committed to this institution, you have a lot, you have, you know, about as much power as you can have and still be a woman in this institution.

Christena: How do you, like, don't these, like, rules and regulations and the patriarchy, like, doesn't it just, like, deflate you all the time? And she's just like, the bishops will die. And I was like, that is so morbid.

Christena: I was like, are you planning on, I mean, like, it just makes you wonder. But it's so true though,

Amanda: because like, like the Catholic Church is nowhere where it once was. Yeah.

Christena: And also like, she's just like, they, like, they don't have the last word. They don't have the last word. They don't get the last word. We don't know the whole story.

Christena: And it's like she was just so unbothered and that to me felt like that mystical like right she's obviously only aware of what the Catholic Church is. Right. And also, she's like, I'm not gonna, they, I'm not gonna let them bother me I'm going to keep doing my work, because we don't know the end of the story.

Amanda: Yeah, there's a saying about that, kind of, in witchcraft, well, I guess I kind of partially put it there. I'm drawing from some ideas in witchcraft where I think about, um, desire, you know, and how in witchcraft, like, you're essentially supposed to, like, really listen to your true desire, your kind of true will, and then follow that because That's like a desire that's put in you by the goddess because she needs something done.

Amanda: And you don't know what that is. And you don't know why that is. And I think about that kind of like a beaver where, like, a beaver is just like, that wood goes in that water. Like, that tree needs to be In that water, because I want it there. I have a desire to put it there. I'm not questioning it. I'm just going with it.

Amanda: And then that creates these wetlands that attracts insects that attracts birds that attracts, um, trees and for so the beaver essentially by following its desire to put that would in the water is. Nurturing this whole forest, but it's not thinking, you know, I'm gonna do this whole ecological project and, you know, rehabilitate these wetlands.

Amanda: It's just like, Nope, that that log cannot stand. It needs to be over here. So I see it kind of like what that woman was saying, you know, like, we don't know how it's gonna go. We just need to, I feel like we just need to follow the desire, but the trick is to know which desire, like, because a lot of desires are put into us by this like capitalist machine, which maybe is like doing something that we don't understand, right?

Amanda: Like, maybe we need to do all this so that we can get to another planet someday or something. We don't know why that is, but, um, but I feel like. In, in Witchcraft, the idea is like that your true will can't, it won't be your true will if it impedes the free will of some other being. Like your, your true will cannot be to hinder the free will of someone else.

Amanda: So, yeah, do as thou will, shall be.

Amanda: You both have the time or energy or inclination to maybe take a question from our coven mates who are here.

Christena: What's your time

Amanda: like guys? We're at the hour and a half. Are you, do you have a hard hour? I can stay for like another 10, 10 or 15 minutes. Great. So, Kevin, um, if you have a question, you can unmute yourself now, or maybe you can raise your hand if there are no questions.

Amanda: Just, oh, here goes Lisa running toward her, you know, it's question time. Hi Lisa. Hi. Hi. This has been such a great conversation to listen to. Thanks, everybody, for being here. Um, I was raised by a mother who loved science fiction, and I Really understood, like, the science of the cosmos, but to my five year old mind, anyways.

Amanda: Anyways, so, like, we didn't go to church, we weren't that kind of family, but I had church families around. Really understood that context from an outsider view. But I think, like, the Big Bang started the universe and everything is just, like, on this trajectory outwards from that. Spiraling, swirling, and, uh, so that's where I derived my sense of spirituality, too.

Amanda: Thinking about if we are like the idea of obligation, like you're going to do the thing that you've been given. For the world, that if we are each these like particles flinging outward from the great big bang, that we each have unique properties amongst us. And that, um, I don't know, maybe the goal, the ideal is to fly as far out from the center as you possibly can.

Amanda: And the best way to do that is unimpeded and without banging into others, pushing other people off course or whatever. So that obligation is like. Find your perfect balance in the sense of, like, you are a moving particle in a moving universe. Find your balance

Christena: and move through it freely

Amanda: without bumping into others and causing them to go off course or causing yourself to go off course.

Amanda: And, like, maybe we do sometimes bump into each other and propel again more further outward, but, um, you have a duty to, like, find your spin and fly. Find your spin, yes. Anyways, that's what came up for me while I was listening to you guys. That's so interesting, Lisa. I was thinking about it in such similar terms like last night as I was falling asleep.

Amanda: I was thinking about just being these like threads of energy and, and that sometimes magical work or like spell work is, is hoping I can draw intersect with mine for just a sec. Like just maybe we could share this point of intersection. For just a moment. And there would be some energy created there.

Amanda: Thanks so much for sharing that. I love that image got to find your spin.

Christena: I love to how that ties into what Amanda was sharing about your true, your true will being something that's not going to impede someone else's free will. I think in the context of community, what that means is there's consent. I'm consenting to letting your will impact me. Um, and vice versa, which to me kind of gets at the finding your spin and like what happens when you do cross paths.

Christena: My spin cross paths with someone else's spin. Well, then the question then is, do I have your consent to bump into you and be transformed by you and vice versa? And in my, I do a lot of interplay, which is like embodied wisdom play for adults. And, um, we often skip backwards just to like try something new.

Christena: And if you bump into someone else, you just say, you're welcome, instead of I'm sorry. Because we've all consented to participating in this practice together in a group, right? So of course, I'm not just randomly bumping into, you know, but it's like, but what does it look like when our spin is in balance with other people's spins in the, in the context of consent?

Christena: That to me feels like that's where the, that's where the big bangs happen.

Amanda: Yeah, and so much of community building is this, right? Like, I mean, I, yeah, I've done this in different realms for so long and so much of it is like, Do you feel like you can leave? Are you going to get a shit ton of pressure if you leave?

Amanda: Are you going to feel relieved if you really, if you leave? Like, what does it really feel like in your body to be a member of something? If you take a, like, that's one of the big pieces of advice given to people who think they might be in a cult. It's like, what happens if you take a break for a month?

Amanda: Are you going to get a bunch of shit or are you going to be okay? Like, you know, how do we, how do we, are we giving ourselves consent to like, listen to our bodies where we feel happy, where we feel safe, or we just, I mean, so much of our culture has desensitized us to our own feelings of not safe or our own feelings of empowerment.

Amanda: So it's hard to even know if I feel good in a community really have to take the time to listen to that. Okay. Thank you. Yeah. Thanks for bringing this conversation to so many spinning, beautiful, wise places. You are two of our favorite writers. Um, can I say one thing about that? Yes, please. Just want to add a little bit.

Amanda: Um, yeah, it really, everything all y'all are saying really reminds me of just the idea of relationship in general, because Like, and the kind of beautiful, like, purposelessness of existence and that. Like, we can intersect with one another, we can run into one another, and that's when relationship happens, right, which seems very beautiful to me.

Amanda: And then we can get in relationship based on consent. And still bad things can happen, right, like, you can get in a relationship, it can break your heart, it can destroy you, and maybe you both were like, let's do this, and maybe it still hurt you. And um. And then maybe you split apart and you come back together at some point, or like there was some purpose later on that like only because you were in that relationship could you be in this other relationship with that turned out way better, whatever, like the story never ends, you know, like, and so really, it comes down to like, what do we want?

Amanda: If there's, if there's not, like, you know, maybe there is a purpose or a reason to the suffering that happens. Maybe we don't know what that is. Maybe we'll never know. But in this moment, we get to be like, what do we want? What do we want to do together? How do we want to create this together? So that's, that's what you're, you're Adams propelling through the universe brought up for me, Lisa.

Amanda: I love, um, Adams. In the universe and we four being four of them. Thank you so much for going into the deep soil with us for spending Equinox with us. Amanda, I want to thank you for Initiated. I want to thank you for Mystery Cult. I want to thank you especially for writing the foreword for our first book.

Amanda: That was a great treat. Thank you so much for inviting me to do that. How can our listeners support you? I want to thank you, you all here for having me today. This has been such an enriching conversation. And thank you so much, Christina, as well. Like what a treat. Thank you for introducing me to Christina.

Amanda: This has been such a blessing to, um, be able to be engaged in this beautiful conversation. And, uh, yeah, if you want to know more about my work, I suggest you check out my cult. Join my call at AmandaYatesGarcia. substack. com. The first level is free, so there's no obligation. And even if you join and then want to leave, that's totally fine.

Amanda: Um, and then the newsletter is so magical and fantastic. It really is like a treat to receive. So I would recommend all our listeners go and do that right now. Thank you so much. And then, um, yeah, you could check out my book, Initiated, Memoir of a Witch, or follow me on Instagram at oracleofla. You can also book an appointment with me for a one on one divination or healing or ritual session.

Amanda: I will say, it was many months ago that, um, Rhys and I were like, what if we could get Christina and Amanda into the same room? Like, like, like, you just had a sense, like that would be a good combo or, well, let me

Christena: say, what were the chemical, the chemicals being imbibed at the time when that came out?