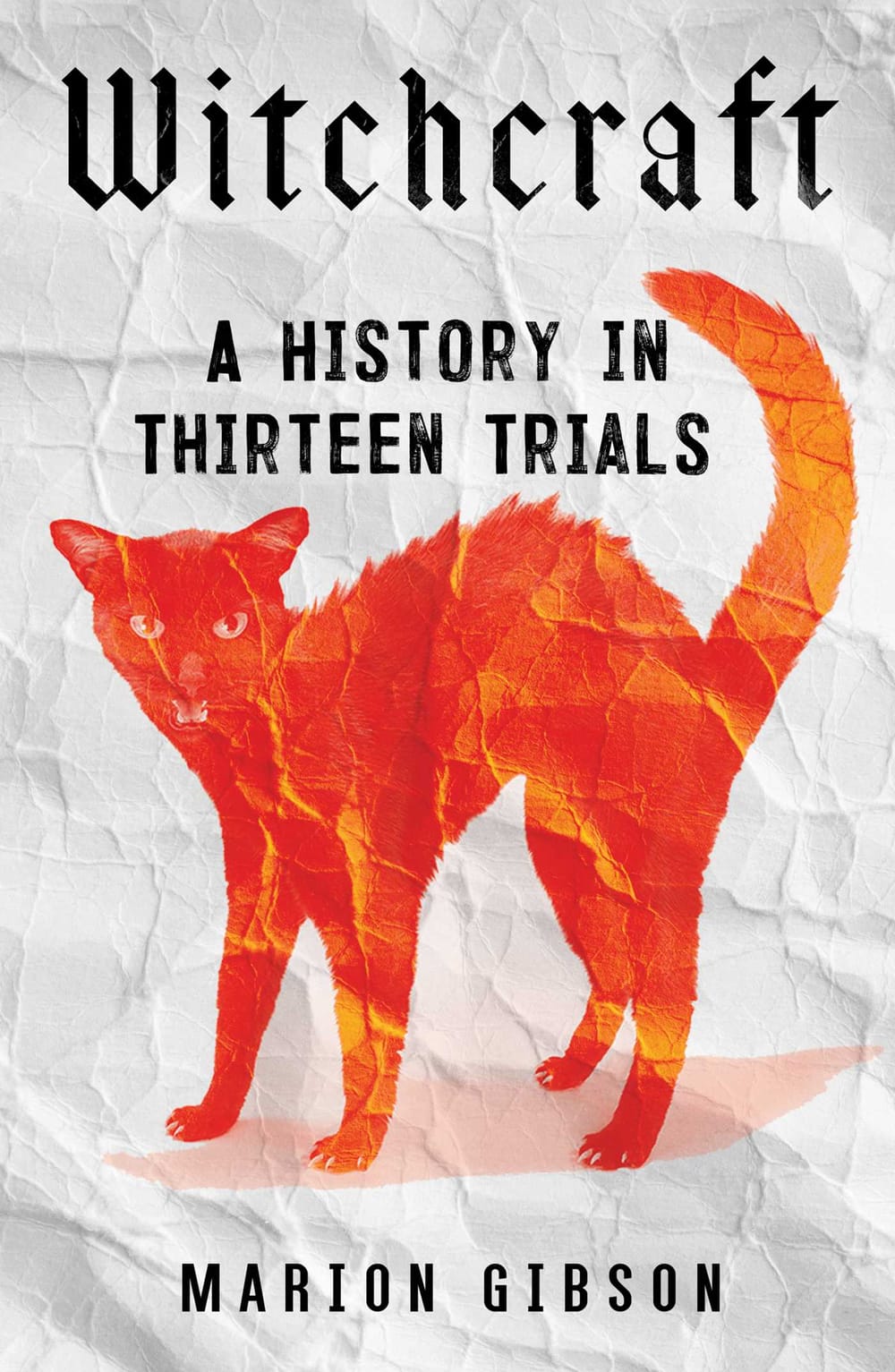

In this week's episode, we get to meet Dr. Marion Gibson, a leading authority on the history of the witch trials. Throughout her career and especially in her latest book, WITCHCRAFT A History in 13 Trials, Marion haunts the archives, trudges in the footsteps of the women accused, and of their panicked accusers as well.

I do feel that records lead you where they want you to go. And that's something that I think a lot of historians feel. Most of them don't talk about because it sounds kind of magical, doesn't it? But they do, you know, you find things because it almost feels like they are waiting there for you.

She brings their lives and socio-political circumstances alive and helps us think about what it means to be seen as threatening just for existing as we are.

What is a witch? From the time of its invention “the witch” has changed shape many times, yet throughout history it has been used to subjugate, persecute, and marginalize. As it investigates the history of witch trials across seven centuries, WITCHCRAFT draws together a narrative of how the witch came to be, how its definition was twisted throughout history to suit the needs of the moment, and how it has never truly gone away. Along the way, Gibson aims to tell the witches’ stories from their own perspectives, combining newly researched information about who they were as people with context about the world they existed—and suffered—in, filling in the gaps that history, with its long-held focus on white men, has so often left behind.

Transcript

Marion Gibson

The Missing Witches podcast is brought to you by the Missing Witches Coven come find out more at missingwitches.com.

[00:00:17] Risa: listeners, welcome friends, welcome coven mates, welcome mountains of snow, kids with a racking cough, home for five days in a row, sleepy brains. Welcome all of us surviving as best we can. under terrorizing conditions of late stage capital. And also, welcome to all of our hopes and joys and excitements and just the real delight and honor that personally I feel here today in getting to meet someone who comes with such a life of research into something that I care so much about and I'm so excited to get to learn about from the source and I'm really thankful Dr. Marion Gibson. Marion is here. I'm really thankful for this book. I've dog eared witchcraft a history in 13 trials, which I think according to a recent instagram meme means that I'm chaotic evil. I wrote all over it and folded all the pages. But you can also feel reading this book the like, hundred other books that are behind it,

so I, I, I really feel the presence of all of that work and all that labor and I'm really thankful for it. So thank you so much for being here. How are you?

[00:01:30] Marion: Oh, I'm very well. It's a pleasure to be here. And I was so pleased that you've written in it. I like to write in books too, because it's like having a conversation with the author and having a conversation with yourself about what you found in there. Oh, I must look this up or, or really like this. bit.

Yeah. I love that. Good.

[00:01:48] Risa: Me too. I feel like also when I encountered those books later, I know how much I loved them. If I really docked them up.

[00:01:55] Marion: Yes. The more folded down leaves it has and the more little bits of marginal note it has, the more you think, Oh, that, that book meant something to me. Yes. And I love that. I love that. And I love that that you've done it with, with my book. Thank you.

[00:02:09] Risa: Yes, I have, there is so much research here. I wonder if you could situate this book.

Some of the research that went into telling these specific stories, and also within your, your life's work, so folks can get a better idea of what that's been like.

[00:02:24] Marion: Yes, there is a lot of research in it. Yeah, and this is why I'm now so tired. yes, I'm not going to deny that there is. So I, I've been interested in the history of witches for about 30 years now, which feels like a very long time when you say it like that, doesn't it? But actually I started being interested when I was an undergraduate at university.

And that was because somebody gave me a kind of early modern newspaper, basically a pamphlet about a witch trial. And I was just so fascinated by this thing. And I still am really, you know, I still go back to that first sense of excitement of encountering these stories and, and it still works for me.

I'm still excited about them. And I was excited because. It was about women primarily, and I found that really interesting because of course, you know, sources from the 16th, 17th century are often not primarily about women, or if they are, they're about them in ways that we now find problematic, like stories of witchcraft.

So I was interested in what those women were saying about their lives, the women who'd been accused. And the women who'd done the accusing of them, because of course, not all the accusers were men by any means, it's quite common for women to accuse one another, as I expect you guys know so it's really interesting from that point of view.

And it's all kind of spun out from there. But this book, it really was a lot of work. I mean, it's seven centuries of research. And I learned a lot. During the course of it, I spent a lot of time in libraries and also a lot of time in archives in record offices going through old documents, which is something that I absolutely love to do, but isn't particularly easy.

And I tried to put as much in as possible because what I wanted to do was make it as. Detailed as possible and try wherever I could to really foreground the story of the accused person and try to put them at the center of it and where I could to find words that they'd actually spoken. Or if I couldn't find that, then at least details of their lives, you know, stuff they might've seen on a daily basis, stuff they might've thought about, try and work out exactly where they lived and what that might've felt like for them.

So it was all of that. It was the nitty gritty stuff. And that does mean a lot of digging, but I really wanted to do that to put them at the center of their story, if you see what I mean.

[00:04:46] Risa: Yeah, I absolutely do. And I think that's something you can really feel in the book and it really feels so I mean, some of it is so sad and so traumatic to read, but it also really does feel like, Oh, finally, like I wanted to see who these people were, like, even if I can't get more concrete data. Just to put them in the perspective that you did, what was it like?

What was the town like? What were the social economic strings that were being pulled? What, what was the racial background of the people involved? It gives us more insight, I think, especially when you bring that conversation into today, where that words or the phrase witch hunt is getting slapped around by everybody.

I wondered from the perspective of these trials. Could you think out loud about who witches are, who witches were, and maybe outside of the perspective of persecution, who were they?

[00:05:41] Marion: It's a

[00:05:42] Risa: another book kind of specifically about that, but yeah.

[00:05:45] Marion: Well, yeah, well, yes, yes, I do. But I think it's a question that's always worth keeping asking ourselves. And one of the things I learned during this, but you know, I'm a historian. I basically look at the past, but I wanted in this. to bring it up to date, because like you, I was increasingly noticing that people were talking about witch hunt.

They, they were actually believing that other people might be doing magic. And I thought that was really interesting. You know, the world was kind of on the one hand being re enchanted, which is nice and good. And on the other hand, people were using the word witch as a, as a hammer to beat each other, which is.

So I wanted to bring it up to date. And I learned a lot about what I thought a witch was because of that, really. I mean, I'd always thought, okay, so they're primarily women. We, we know from, from the period of the witch hunt, really the 15th to 18th century or something like that, you know, when there are lots of witch trials, we know that there are about 75 percent of those accused of women.

And in some cases it's much higher, it's 90%, it's 100%, but in others it's much less, and in some jurisdictions men are the majority, but they are a fairly small number of jurisdictions. So I was thinking, right, they're women, that is primarily a story about the lives of women, although not exclusively. And then as you go on beyond that, you think, well, what kind of women are they?

So they're quite often women who have stood out in their community in some way, either for good reasons in their own terms or bad reasons. So you, maybe they've had quarrels with neighbors or maybe they've been accused of something like heresy, some sort of religious crime, or maybe they've, they've. been accused of some sort of social crime, as it was then considered, you know, perhaps they have an illegitimate child and the church is upset with them.

Or perhaps they've had a history of various sexual partners, which appears lurid to the people around who, you know, imagine that they're going to spend their whole lives in a. A monogamous relationship. And once they're married, that's it. And that's how they think about themselves. So anybody outside of that, they think, Oh, well, the, you know, this person is deviant, this is very bad.

So I was kind of looking for those sorts of women who'd done something a bit different with their lives and who stood out and their neighbors could see them and then beyond that, I was thinking, what else are their economic circumstances? Quite a lot of them are poor women. So they're, they're women who are struggling on the margins of society, but there are also rich women, which I think nicely makes the point that, wait a minute, this is about women, isn't it?

It's not just about economics. It's not just about all the things that historians will often tell you that witchcraft accusations are about. It's about women. Can we pay attention to that? So I thought all those things were important things to draw out. And then of course, I started looking around the world, you know, I really started my research in Britain which isn't very racially diverse in the early modern period.

But of course, as I started to look at more modern times, and then I moved across the Atlantic to look at the, the early American trials, whether that's in Virginia in the 1620s or Salem in the 1690s, then I started thinking about race, so I started thinking about Native America. And then I looked, you know, in other places in Europe to see what I could see in, in terms of that sort of diversity.

So one of the chapters looks at Northern Norway, which is something I really hadn't considered before I started writing this. And there I found colonists, settlers, people coming up from the South in conflict with the people of the Arctic Circle. So the witch is also sometimes somebody who stands out in other ways.

Maybe she looks different from the people around her. Maybe her language is different. Maybe she has different religious beliefs, different practices. So those are the sort of people that the book is about. People who get noticed for the wrong reasons and are persecuted and victimized and scapegoated because of that.

And as you move into modern times, you can see they are often the same kind of people. Of course their circumstances are different. But I think you can still count them as witches. And the people in the book are people who've on the whole been accused of some sort of magical crime. And that in my book, literally in my book, makes them witches too.

So I wanted to trace that throughout history, that sense that we're dealing with marginalized people who are in trouble with the society around them.

[00:10:08] Risa: And it has something to do with the changing idea of magic, right? Like you talk about this right in the very beginning. Can you think out loud about that too? That there, because some of the people are there, they're reading how milk churns or, you know, they do have these folk magical practices, but something changes in the moment that makes that kind of magic dangerous.

[00:10:29] Marion: Yeah, they do. And I think people have always believed in that sort of magic. You know, there's quite a lot of evidence from. prehistory that people are blending ideas of what we might now think of as religion and what we might now think of as magic. And this is the same for people. So this kind of basic human thing is, I think it's one of the ways we think about the world.

But come the religious upheavals in the Christian church in Western Europe and North America in the 16th and 17th century, that All gets very difficult for people to think about. So they start accusing each other, you know, Christians start accusing each other of heresy, Protestant, Catholic, other groups splitting off from those two, two big separating churches.

And then they start looking for people who they think are outside of that. And the whole thing just gets more and more problematic and magic gets drawn into this religious debate because people start thinking, well. I'm not really sure if this person is on, is on God's side or the devil's side. And one of the ways that I might work out that they're on the devil's side is looking to see if they practice any kind of magic.

So do they maybe do magical healing? Do they, do they say prayers in places that I'd really prefer them not to say prayers in? Are they the sort of person who I don't think should be saying prayers or preaching or? standing up and speaking about religious matters. You know, are they, are they a woman quite often, but are they also maybe a poor man or somebody who's unqualified in, in the terms of the church at the time.

So I wanted to look at that way that, that over time, magic had become associated with the devil and demonized. And then in modern times, even though, you know, now we often think of ourselves being more enlightened and more accepting and tolerant and all of these kinds of things, very often you will find that people who are in all those groups that I talked about earlier find themselves being accused of some sort of crime, which has a magical.

aspect to it. So later on in the book, I talk about a woman who's a spiritualist medium and how she's accused and dragged off to court. And I talk about faith healers in Pennsylvania in the 1920s. And then I bring it right up to date and I talk about Stormy Daniels, who, who, been, you know, is a pagan and has been accused in witchcraft in quite straightforward terms as part of the general debate around her role in modern American politics.

So I've tried to find examples throughout history of where magic has been regarded as a bad thing rather than a good thing, which I think is how it might've been regarded in the various, very earliest of human societies.

[00:13:05] Risa: And what do you think about trust? These days, right? I want to read a little piece because I want to hear you talk more about the relationship between witch hunting and colonialism. You, you identify these different moments where, the Sámi indigenous woman and you give her a different name, Tituba Tatabe, than I had seen before, but really identifying these moments where, and, you know, we've seen it in Colombia and in the Philippines where inquisition or witch hunt is really used as part of a colonizing endeavor, can you talk about I love this quote I'm going to read your writing at you. That's okay. So, you wrote "scholars have recently suggested that the earlier transatlantic trade and enslaved people was seen by its victims as a type of witchcraft, just as they had previously imagined, which is metaphorically consuming happiness, fertility and wealth.

So some enslaved people describe themselves as victims of witches who they thought would literally eat them. in Barbados or Boston. Together with redefinition by incoming Christians, this new conception of witchcraft as slavery may have destabilized traditional beliefs. A study published in 2020 claims in Africa and North and South America, representatives of ethnic groups that are more severely raided during the Atlantic slave trade era are more likely to believe in witchcraft.

This hypothesis doesn't explain everything about contemporary African witchcraft trials, but it points to links between colonial violence and the legacy of social mistrust." Trust broken down. I have like seven more paragraphs outlined. I'm realizing it's a really long thing to read, but would you think out loud about that

[00:14:37] Marion: I think that was one of the things that I found most interesting because, you know, somebody who writes about early stuff, some of the more recent witchcraft accusations. So for example, the ones that I write about across South Africa were the ones I knew least about. So I went chasing what other scholars have to say about why they thought witchcraft belief was so prevalent there and why people were so violently persecuted. I mean, hundreds of people are being killed as witches across Southern Africa, but also in other parts of the world, parts of India, Nepal parts of Indonesia.

And I wanted to think about that. We spend a lot of time telling ourselves how rational we are today and how we would never do that and all those kind of things, but it turns out they're not really true. So I thought it was important to look at that and to look back at the long history of people exploiting other people and see what kind of place the idea of witchcraft had in that.

And what that report by those scholars that are cited in the chapter argued was that it's the exploitation which turns into enslavement and turns into the transatlantic trade in enslaved people is inherently connected to ideas of magic because the people who were enslaved already lived in a magical world, you know, as lots of people did in that period and lots of our own ancestors in Europe and North America did too.

They perceive what was being done to them as some kind of magical exploitation because they couldn't think of another way to, to explain it. You know, their whole world was being dismantled. Their culture was being destroyed. They themselves had been captured and dragged away to a place which was utterly strange to them.

And they had enormous trouble making sense of it. Some of them took with them their magical practices as a way of trying to make sense of that world. There's quite a lot of interesting archaeological evidence about what kind of things they did. So I wanted to think about the ways that they thought of the world as magical, and they thought of the colonists as witches, which is a really interesting juxtaposition, isn't it?

But at the same time, those who were colonizing their world often were involved in missionary activities too. So we're trying to Christianize them the way that those people thought about the indigenous folks that they were exploiting as witches and use the idea of witchcraft accusation against them.

It's really complicated because the people, the indigenous people who are living there are very often people who believe in witchcraft and accuse others of witchcraft. Yet, the colonizers still managed to find a way to make the witch trial count against them. Whether it's saying, Oh, you know, you superstitious people, you're accusing each other in witchcraft.

This is bad. Therefore, we must civilize you and take your country from you and colonize it. Or, They're saying, Oh, well, actually, you know, you are practicing witchcraft. This is very bad. We must take your country away from you and colonize it. So witchcraft gets very much mixed up in discourses of colonization.

It seems to me. And I thought it was really important to talk about that because again, it's something that we see a lot in the world today and it helps to explain why witchcraft accusations are so common in parts of Africa, India, Indonesia, and so on.

[00:17:47] Risa: I want to know what you think about, so as someone who I have a witch podcast, I'm really interested in the word and in the identity, you know, gives me power and I'm interested in the history and the sort of intersection between politics and art and grounding in a spirituality after not really having any, and just in the community it gives me.

But I Fear that you know, the other pieces of that, that like, entertaining, exploring ideas around the unknown makes us more vulnerable to conspiracy theories, or that building a community embracing ideas of witchcraft somehow makes it more dangerous for people who are being accused of witchcraft because we're somehow giving validation to the idea that witches are real.

And, you know, you've done all this research right at the intersection of this question, the way that this word gets used against people in this sort of flip floppy violent way. What do you think about that these days?

[00:18:40] Marion: Yeah, that's really interesting. And it's a really insightful thing to say that, that, you know, by ourselves believing in magic and witchcraft, are we in some way saying, Oh, well, you know, the witch trials of the past are fine. And the witch trials of people in contemporary Africa is fine because yes, they actually are witches.

So there we go. It's really difficult to think about, isn't it? And when you look back at the history of people arguing against witch trials, Some of the first people to do so were 18th century folks who looked at the history of the past and said, well, it's just superstition, isn't it? You know, we're radical lawyers of the 18th century.

We're French revolutionaries. We're going to stop believing in religion altogether. Not just witchcraft, but everything, the idea of a supernatural world, the idea of supernatural beings, you know, just throw out the angels and the fairies and the spirits of the past and God and the devil and demons and all of it, just get rid of all of it because that's the only way the world is going to be safe for people.

And they won't be accused of witchcraft anymore. And I think that's a really powerful thing to say, you know, it kind of appeals to me that level of right blank slate, let's just start here and let's only believe in things that we can verify with our own eyes, et cetera, or let's reframe the world in ways that we think, well, it will exclude certain things, but we don't mind losing those things.

If it means we also lose witch trials, I think that's a really powerful thing for people to have thought. But. I think that what it does is, is often, it does strip the world of that sense of, of, Well, magic, I suppose, you know, the beyond the fantastical and you see at the same time as people are trying to desacralize the world in that way in the 18th century, get the rise of stuff like gothic literature.

So you get all the ghosts and the angels and the demons and the witches, all kind of creeping back in through the back door and you know they bring with them stuff like vampires and all the kind of. figures that we actually really like to think about. I think there is something intrinsic in the human mind that wants all of that stuff.

And you know, who am I to, who am I or anyone to deny it to people? If that's the way you see the world, then great, that's fine. It seems to me the key thing is, you know, this is part of modern Wiccan's creed, isn't it? And, and which is creed, you know, depending how. People identify themselves. It's about not harming people.

So in a sense, it doesn't matter to me, as a historian or as a person, what people believe in, so long as they do it in a way which is tolerant and careful and avoids causing harm. I think there's a lot to be said for re enchanting the world because quite often it can bring back the idea of a connection between people, that idea of community that you've talked about, getting together to create a world together.

And it can bring back a connection with a natural world, which, you know, can also seem haunted and, and empowered and, and, and spiritual in its own way. And I think those are really good things. Yeah. I mean, throughout my career, I've. of struggle with the same sort of ideas because, witch means very different things to different people.

It can mean, you know, hapless victim of lunatic aggressors, or it can mean empowered spiritual person, priestess or goddess. It can mean all those kinds of things. So I've got more comfortable over the years, I suppose. Trying to, to see those things in tension with each other and in balance with each other.

But I think witch trials happen when they get out of balance, and when people start weaponizing them and that's where the danger lies for me.

[00:22:27] Risa: And do you feel like, I guess there's an assumption in my question. Do you feel like first that there is this sort of rise in interest in witchcraft and studying witchcraft? I think there is. And if you do do you think that that is related? Like, I feel like sometimes the question of, of witches and witch hunting and, and whether there's magic, the unknown in science, That it's tangled right up in the complexity of this moment. To think about witches isn't really this fringe story anymore. Because we're right in this, in the heart of this moment of like, is, is an enchanted world possible? Like, is, is, is a, is a liberated world possible? Or, or are we just fucking doomed?

Do you know what I mean? it feels like really urgent to engage with it somehow.

[00:23:13] Marion: I think that's right. I think your assumption is absolutely right. People are more interested in witches now. Witches are having a moment. And I think they have been since at least the 1990s and probably before actually, you know, you could also look back to the, particularly the feminist movements of the 70s and 80s, when people started being interested in reclaiming the idea of witchcraft in modern times.

Although the book also looks back to Victorian people who were interested in that too. So I do think it's been going on for quite a long time, but I think since the 1990s, it's really been hotting up, if you like. And people have become more interested in what the witch means. And that is partly because of that idea of trying to re sacralize the world so that ultimately you don't blow it up or destroy it in other ways.

I think you're right. That does feel pretty urgent, doesn't it? But also people have become interested in it maybe in just the past five or six years, really, as, as we've seen increasing misogyny in the world. And, and we've started to think, well I started to think that some of these problems just haven't gone away.

We haven't changed things as much as we maybe thought we had, or thought that we should have done. And words like witch do retain a relevance therefore. It must at one time surely have seemed that witch was a word you would only use about the past. But actually now here people are being accused of witchcraft in the present and people are still finding the idea of the witch powerful.

So, yeah, I think there's a really interesting and quite lengthy cultural moment happening around the witch. I don't know how it's going to turn out. No. And as you say, you talked about conspiracy theory earlier. It's. The intersections between ideas of magic and witchcraft and ideas of conspiracy theory really interesting, aren't they?

Because conspiracy theory often leads us, at least, in my view, into places where we really don't want to go, where you know, we end up in this kind of post truth world and anything goes and people can make up any kind of awful libel against other people and find ways to, to force it upon them.

And that, you know, that's a bad thing. So is it possible to be too magical? Is it possible to re enchant the world too much so that we've moved away from the 18th century lawyers and their insistence on provability and we've moved towards, it doesn't matter if you can prove it or not. Could be true anyway. I don't know. I don't know. I feel, I feel enmeshed in it the same as you do, but I do think the witch is a really powerful way of talking about that. Cause the witch is right at the center of that long history of humans trying to work out how the world works, what our place is within it, how we're supposed to relate to each other.

Is there, is there a world beyond, is there a supernatural world? Yeah, the witch helps us think about all of that. And I think that's really quite important to have that discussion.

[00:25:59] Risa: Totally, and you make me think, I mean the invention of the witch by historians sort of wanders this line between like really great history and You know, as you, I think, really kind of lovingly point out, like, an invention that used history in a way that was quite creative, that sort of helped us get to a sexually liberated gender, you know, defiance of norms, way of thinking about witchcraft, but, but that that history was kind of fuzzy, like the Michelets or Doreen Valiente or Margaret Murray.

Can you talk about Yeah. That way of doing history that's sort of problematic, but sort of gifted us some stuff?

[00:26:37] Marion: Yeah, I totally can. That's something I've developed increased tolerance for, you know, when I first started out doing history, just like, no, these people are wrong. We're not discussing that. That's just wrong. It didn't happen like that. History wasn't like that. You know, the 16th century women were most likely not nature loving goddess worshipping pagans, but The idea that they might have been is super powerful, isn't it?

And I gradually came to have much more tolerance for that idea because I could see that the historians like people like Jean Michelet, who were putting it forward, really had their hearts in the right place. And I thought that went rather a long way towards my feeling warmer to them. So the first time I read Michelet's book, you know, I was going through, I think I may even have written in the margins.

I don't know, I had a cheap 70s paperback that I've still got. I may even have written no, every now and again, in the margin. No, you know, I'm really sorry, but

[00:27:34] Risa: No.

[00:27:35] Marion: empowered pagan priestesses. I wish they had been, but they weren't. They were just medieval women who were struggling with a church that wanted to silence them.

But then, you know, once you start thinking, well, yeah, they were struggling with a church that wanted to silence them. What if somebody in the 19th century, Wanted to reinvent them as pagan priestesses. Who am I to stop him? So yeah, I, I think the ways of thinking about the history of witchcraft need to be more open actually.

And I think we've kind of, there's a, there's a phrase throwing the baby out with the bathwater. I don't know if you have that, but we have that. That, you know, you've thrown away the precious thing in an attempt to rid yourself of the, you know, less good thing. And I kind of feel that historians have sometimes got a bit too interested in stuff like, you know, the economics of history or stuff about, you know, social relationships and class and, and so on.

And, and they perhaps noticed a little bit less, look, these are women, look, they might have unusual religious views. We sometimes don't know, but sometimes it's quite clear that they did have some heretical views. Maybe they weren't pagans, not in the modern But what about all that folklore that they knew?

What about the stories that they told each other? It's worth listening to see if you can find those things, isn't it? And so I think it's important to pay attention to the Michelet's and the Valiente's and even if you will end up thinking, I really don't think. history was like that. It's always very nice to play the game of what if it was and to see the difference they've made to the modern world, which is perhaps even more important than interpreting the past.

It's the difference you make now. So yeah, I do like those sorts of writers, even though at the start of my career, I really didn't,

[00:29:20] Risa: I love that answer so much. And I was on mute, but you made me laugh so hard when you said you've increased your tolerance for them.

[00:29:27] Marion: which is a good thing, right? You know, that's, if you write about witches, surely you should become more tolerant over time.

[00:29:35] Risa: I really love that. And I do love thinking about, I'll interrupt myself to say, we have members of our coven here who are witches practitioners, academics, artists from all different kinds of perspectives and worldviews. I will invite if you do want to ask a question or just engage in this conversation, I'm going to make sure we have time for that.

BuT I wanted to ask, you know, when we're thinking about these stories, you know, like. Women of the 16th century, what did they really believe? How can we really know? Or even going further back, right, talking about colonization from the perspective even of Roman colonization, you know, or burning sacred groves.

What, what were these, what were these, like, longer memories that people maybe in the country were holding on to? As a researcher, I'm not sure. What do you suggest? What are some practices of often I ask people for like a ritual or something they're doing right now, but I'm going to ask you for a research practice instead.

What's a research practice you suggest for us when we go looking for these stories, especially stories that exceed the archives, women's stories, the stories of colonized enslaved people. There's a lot of places where we don't make it into the archives. How can we connect to those stories?

[00:30:59] Marion: Yeah, that's a great question. And you know, it pushes me. in a direction that I've been going for some time, which is seeing the practice of researching history as being an emotional one, actually. You know, having emotional engagement, it does have elements of ritual that the pleasing aspects of historical research, the going through the catalogs, the going to special places to do the research, the immense privilege of being able to touch the original records and find names in them that you recognize, you know, that's, it's, it's kind of a church and therefore it's kind of a ritual.

So I, I, yeah, I, I, I hear you when you say, hang on, this is kind of like the moment when you ask somebody about ritual. The things that I do, I suppose. Would be try and go to the places where the people lived if you possibly can. If there's any way you can get to any of them and walk around in them and, and try to see what they see.

You try to feel what they felt, you know, is it cold there? Is it hot there? What if you shut your eyes? What can you hear? What do you smell there? What do you know from the records that they might have smelt there in the past or seen there in the past? You know, if you shut your eyes, can you imagine what that might have?

look like? What does the landscape look like? How do you feel there? Is it a flat landscape where you feel exposed? Is it a hilly landscape? You know, what's going on in it? Is the sea there? Is it, is it a big open plain? What is it? So I found those kinds of things really useful and sort of walking around as far as you possibly can in the footsteps of the accused people or their accusers, I think is, is.

It's really interesting. It's certainly something I've done in a previous book called The Witches of St. Osith that I wrote. I went on this kind of 11 mile trudge. I won't dignify it by saying it was a hike or a, you know, a trail. It was a trudge round, round muddy lanes in Essex, Essex County in England.

And I tired myself and I allowed myself to feel kind of vulnerable. You know, I was, I was staying in a kind of glamping place and it was cold. It was January just for the pandemic, which of course we didn't know was coming. And, and so I tried to feel the way they might've felt these, these women who were accused of witchcraft subsequently.

And they'd gone round from house to house, farm to farm, begging for charity and, you know, often been turned away, often had crosswords with the householders and something terrible happened to the householder. And they thought, ah, you know, it's that person who came to the door. She cursed me. That's what it is.

But I thought it was important to do. It was important to slip in the mud and it was important to have sore feet. And it was important to be hungrier than I really wanted. to be and tired than I really want it to be. And just think about what those people might've felt like. So I do all of those things.

And also I do feel that records lead you where they want you to go. And that's something that I think a lot of historians feel. Most of them don't talk about because it sounds kind of magical, doesn't it? But they do, you know, you find things because it almost feels like they are waiting there for you.

They are waiting to be found. Some stories want to be told. Some stories maybe don't want to be told, and those are the harder ones to get out of the archive. But I do feel that, and I just feel, I just feel, I feel so happy when I find the story of one of these people, and I trace them, and I care about them.

I think caring about history is really important. And I increasingly less trouble about saying any of that, you know, when you're in a kind of early career academic, you don't say all that stuff necessarily, because you want people to think of you as a kind of 18th century lawyer figure who is rational and focused and orderly and has a strategy and all of those things.

But the older I get, the more I think, no, you know what, that isn't how I do things. I kind of putter towards things, you know, feeling about them. So it's guided by emotion. It's guided by something that might be instinct or might be experience, who is to say It feels kind of magical. So it does, there is, there is an element of ritual, I think, in historical research.

And if people want to follow that and go after a figure that they feel some empathy with in history and try to research their story by going to the place that they lived or doing the things that they did, I think that's all brilliant. I do think people outside of academic institutions can do really good history in that way.

[00:35:22] Risa: I feel emotional hearing you say that. Many of the stories in your book made me very emotional. Because I, and especially the first one, like Helena, you know, because it's such a, it's such a wrench, you know, I'm so proud of her and of her community.

But to know that that is the kernel story behind her, her prosecutor, behind so much of what comes next, it's really, really bittersweet. Are, are there moments in the book that were really emotional to discover?

[00:35:55] Marion: Yes. Absolutely. Yeah. I think Helena's story. So the first trial, you know, set in 1485 in, in Austria, where this, this woman, Helena is accused of witchcraft, but she fights back. I think that was a real turning point in writing the book. And I wanted to start the book there because it's a surprise, isn't it?

We often think of witches as hapless people who were victimized, you know, were forced into confession. And that's absolutely true of many of them, they were not able to do anything to save themselves, but this woman did. And I really did find that quite inspiring. Yeah. She, she, you know, she shouted at her persecutor.

She stood up in court. She went and got herself a lawyer. She was lucky in various ways. You know, she had access to the, the level of education, the level of. religious education that the money that allowed her to do that. She had some support from her community, but she did it. She great. So I love that moment.

And you know, and there are sadder ones too. The one that's really engaging me at the moment is chapter five, which is about best clock. A disabled single mother from Essex in the 1640s who gets caught up in the, the big witch hunt in Eastern England led by this chap, the witch finder, general Matthew Hopkins.

And I'm still working on that actually. I'm, I'm still looking at other stories from that group of people. Cause in the end there are a couple of hundred people who are accused across those eastern counties and most of their stories haven't been told. People haven't looked in the archives for those women because they don't tend to look in the archives for the stories of poor women because they think they're not going to, to find anything.

You know, so they don't look, but I would like to find more of those stories because I feel so sorry for people like Bess, who was one of the people who couldn't do anything to save herself. You know, she was in the wrong time at the wrong place and she was unable to save herself.

And we should feel upset about it, because if we don't feel upset about things like that, that happen in history, then we feel less upset about things like that that happen now. And of course we should feel engaged with those things that happen now, it seems to me.

[00:38:04] Risa: Well, yeah, and especially in a, in a current moment, I mean, here in, in North America where the, the attack on women's rights, people's bodily autonomy is so virulent. It's the same, it's the same shit. So it's quite heartbreaking and I think really important to tell these histories.

[00:38:23] Marion: I think so. I think if we look back at the history of, of, Persecution. We can see a lot of analogies with the way that contemporary politics deals with groups who are not able to defend themselves. So, I think that history can tell us a lot. We don't always learn from it, which is a very sad thing.

And we do keep repeating this stuff where we scapegoat and persecute each other. But at least we can tell the stories, at least good people can reflect upon them. hopefully feel a sense that this has happened before and things have been done about it and people like Helena can fight back and I think that's quite important.

[00:38:59] Risa: Yeah, we can, we can fight back. I want to open up the floor - reid, do you want to jump in and start?

[00:39:06] Reed: Yes, thank you very much.

I am a third year PhD student at the university of Georgia, and I am studying the history of witch trials, but my dissertation topic, which is related to this is why women are leaving Christianity right now in America in mass to practice witchcraft. And, I am working on a project right now, I have discovered a woman in the Atlanta Journal Constitution, a ghost story about a woman who was tried in an illegal trial for witchcraft, she was kidnapped And taken to a plantation and was tried and let go.

She was tortured. But she was able to secure a warrant from, I find this ironic, a Presbyterian minister. The ghost story says that she won in court, but was never paid because her accuser fled for the frontier, which at the time was Alabama...

[00:40:01] Marion: that sounds really interesting.

That story you found, that's really interesting.

[00:40:05] Reed: It is. I stumbled upon it in this ghost story, but I've been to the archives in South Carolina and what I found out is that she was a widow and was given a bunch of land and the two people who testified against her that we have record of were her son and her grandson.

And six months after this trial, there is a land record of her deeding a hundred acres to her grandson.

[00:40:30] Marion: So you can imagine what shape that ghost story has, can't you? Yeah. Oh, that's very interesting. Oh, I would encourage you to write about it. Obviously, you know, if this is something that you're studying already, please tell the world about it. That's great. And you know, I'm at the University of Exeter, right in, in in South West England, you know, if you look out for, for opportunities there, by all means think about coming there.

Yeah. We, we, you know, we do a lot of witchcraft and magic stuff at, at University in terms of its history and its literature. So there's, yeah, there's lots of ongoing stuff to talk about, I'm sure. But that's fascinating. And I think one of the things you're talking about there is the way that stories live on.

So, you know, you may not always know exactly what happened historically in the past, but the fact that somebody has cared enough to make a story about it is really important. And I also you know, I write about Witchcraft in literature, everything from Macbeth to the Harry Potter books, I've, I've written about, you know, the ways that witches are remembered in modern society.

So I think that's really interesting. It's a really good field of research and there's an awful lot to say about it. And if you found a case that nobody else is writing about, wow, tell everybody.

[00:41:39] Risa: We'll make sure that you can find each other for sure. Reid's research is so exciting. We always love to get to hear updates from them. I also, while we have you for like two more minutes, there's two other things in the chat I want to make sure to draw your attention to. One was a question from Sarah.

They're asking, and I think this is such a fair question, the numbers vary so widely in how many people were persecuted during the witch hunts, those numbers are kind of all over the map. And so Sarah's wondering how many people were accused, how many people were killed. What do we really know about that these days?

[00:42:13] Marion: We don't know is the kind of big answer because of lack of survival of records. So in some places, you know, record survival is excellent. And that's where you find the best evidence. But in some places, everything before say, like where I live, all The criminal trial records before 1670 are gone.

So we have no idea whether people were prosecuted as witches here or not. I very, very strongly suspect that they were. We'd be hugely surprised if they weren't, but we don't know who they are. We never will know who they are. So that's a really important thing to say, to start with. There's been lots of contentious figures chucked about over the decades, and people have said, Oh, it's millions.

I don't think it is millions of people who were accused and executed. What historians have come to a consensus that we talk about is something like 60 to 70 thousand something like that. So it's tens of thousands, which is a terrible thing. You know, people being killed for something that they have not done. And that many people being put on trial and killed for that is a terrible thing.

It's not the big figure, but it's still a huge figure. But we all recognize that there may be more that we just don't know about, never will know about. And obviously there's a lot of the world still unexplored. by historians who focused on the witch trials. You know, we focused on Europe. We focused a little bit on North America, a little bit on other places, some in South America some in, in the Eastern Europe, the kind of peripheries of the heartland of the witch trials, if you like.

But there's just so much more to find. This is why I'm so pleased to hear that some of you are conducting your own research because there's still so much to say. So I, yeah, I don't have a, have a nice neat figure, which I'm sure you didn't expect me to anyway. But I would say tens of thousands, that sort of figure is probably what we're looking at.

[00:44:01] Risa: It's interesting to think about the times, you describe a witch hunter as "an anxious young man, one who easily imagined himself a victim despite his many social advantages."

[00:44:11] Marion: Yeah. That sounds like Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General, doesn't it?

[00:44:15] Risa: yeah, it was, and what a great description in so many of these cases is people who feel victimized, who truly saw themselves as victimized by something in, in their social dynamic. And often even though they had more social power than the people around them. They were still in a position of feeling destabilized and scared.

And often that has to do, with what's happening in these gaps between rich and poor. I think like people are just feeling scared and uprooted and not having the access to resources they had previously. But

[00:44:47] Marion: Yes. I mean, the world's a scary place. People, people are scared and sometimes it doesn't matter who they are and how much power it might look like to other people they have, or they might actually have. We do tend to, to go around feeling anxious about things, don't we? And one of the things that we have to try and avoid doing is projecting that anxiety onto other people and saying, Oh, well, this is all her fault.

There you go. That explains it. But you can understand, and I, I do understand how people might have come to be accusers of witchcraft and how, of witches and how they might still do that. I've always had quite a bit of sympathy with the accusers because often their stories are just heart rending. You know, you look back to 16th, 17th century England and you think people are wrestling with all sorts of civil war going on.

There's massive religious instability. There's plague. Some people are starving. How can they not feel anxious all the time? And then if within their family, you know, they tell you this terrible story about how their child died or their farm went to rack and ruin, you think, oh, you know, you poor soul.

Naturally enough, you would want to. Try to find an explanation for that. And the one that your society offered to you was, aha, it's witchcraft. So of course you would go along with that, wouldn't you? I think it's really important to have sympathy and an empathy for the accusers too, because they are also living in a very difficult situation.

[00:46:12] Risa: yeah. Do you want to extrapolate that and apply that to today?

[00:46:18] Marion: Maybe, I mean, it's very difficult, isn't it, to, yes, I mean, I feel, you know, I feel enraged in the same way that lots of people do when false accusations are made, or somebody is victimized, or I see people being killed for what I, what I think, you know, is a crime they couldn't possibly have committed. Yes, you know, I feel rage and panic and sadness, just the same as anybody else.

But I think it's probably better from the point of view of intervention to step back a bit to try to feel a bit more concerned for why they're saying what they're saying. They may be saying it because they're evil people, but It might be better and healthier for everybody to look at what are the social forces that cause them to think this, what are the cultural forces that have pushed them to believe this particular thing.

I do feel like we have more in common than divides us really. It's. Hard to hold that line sometimes, but it feels like it might be the better one historically. And as a historian, I'm always trying to look at the long view. So I can see the same kind of impulses across history, but the one that I always try and come back to is, well, you know, we're all just people.

We're all sharing our history together. Maybe there's more that we can do to come together and stop doing this stuff to each other.

[00:47:35] Risa: Thank you so much for that grounding in the long view.

[00:47:38] Marion: It's a pleasure. It's a pleasure. I do feel that we can learn from history. Although, as I say, I sometimes fear that we really don't.

[00:47:49] Risa: here's to the long view, here's to listening in the archives, walking in the feet of people, the tired, trotting feet, trudging through mud of the people who have been violated and accused to really feel each other's stories. Thank you so much to our coven for being here, all of the wise folks who are here.

Thank you to Reid and to Sarah and to Jane who messaged me that it was so profound reading your work in school and she wrote a book and she wants to send it to you, which I'll send to your publisher if that's alright, called Witch Fulfillment. It sounds

[00:48:27] Marion: Quite all right. Yes. I'm so pleased that you're so excited by it. I certainly find it a really, really exciting topic. And it just continues to inspire me. So I'm so pleased.

[00:48:39] Risa: Yeah, thank you so much for being here.

[00:48:41] Marion: I, you know, I love talking to people about witches.

It's just such a pleasure.

[00:48:47] Risa: I hope we have successfully communicated how impacted we all have been by your work in our various academic settings and your thinking and the enormous labor of research to give us back those people's stories. So

[00:48:56] Marion: Yes. You certainly have. Yeah. Yes. And, and I do feel inspired when, when readers respond that way, because I just think, well, great. These are great stories. Let's, you know, let's tell them and, and tell more.

[00:49:09] Risa: tell more. Right, Reed?

At the end of these things, Marion, we often say, blessed fucking bee.

[00:49:23] Risa: The Missing Witches Podcast is created by Risa Dickens and Amy Torok with insight and support from the Coven. Amy and Risa are the co-authors of missing witches, reclaiming true histories of feminist magic, and of New Moon Magic 13 anti-capitalist tools for resistance and re-enchantment available now wherever you get your books or audio books. find out more at com.