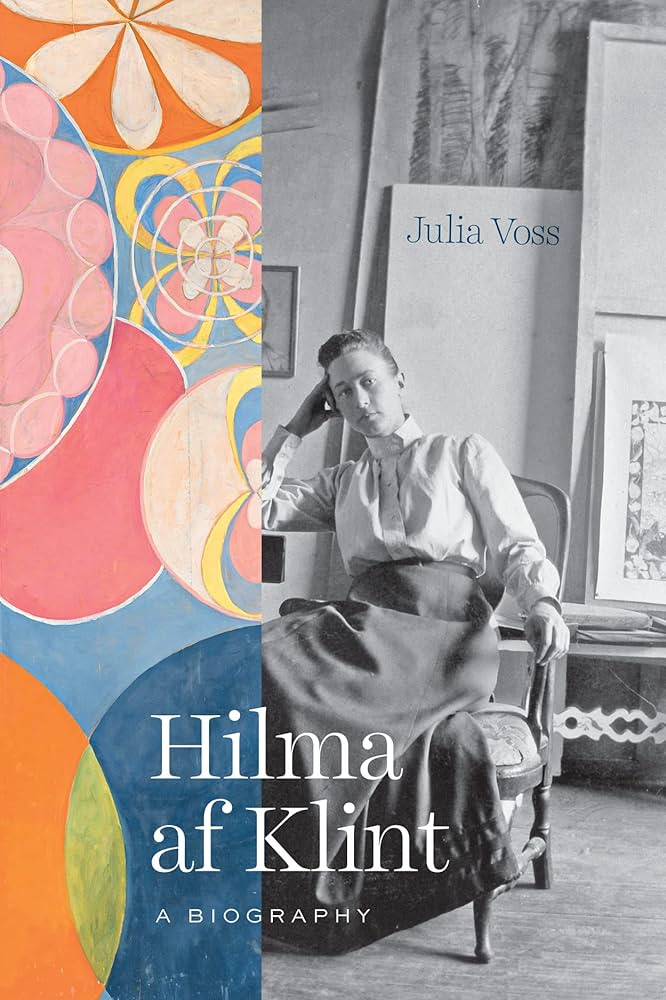

In this episode, Risa gets to interview the primary biographer of the first abstract expressionist artist, Hilma af Klint.

We talk about collaboration between women and spirits, we talk about taking what Hilma tells us of her experiences seriously, we talk about the beauty of her vision, we talk about reaching our feelers out to continue evolving throughout our lifetimes, and beyond.

She develops this very pantheistic attitude towards what's around her. In the beginning you would always have these flowers in her paintings and you would have all kind of organic forms, but then she turns to actual flowers in her environment and tries to channel their souls. And succeeds.

Transcript

Transcript Julia Voss - Put Your Feelers Out

[00:00:00] Risa: The Missing Witches podcast is brought to you by The Missing Witches Coven. Our coven mate, poet, Sun, said.

"I came to this coven because nobody else was centering mutual aid and informed resistance like the Missing Witches, but this community is also hugely loving and supportive and full of artists and thinkers and healers who have such a huge diversity of experience.

Even when we're not in circle, there's magic afoot. Also, I have a chronic illness, which makes it really hard not to swear all the time, so I am in fabulous company here. Blessed fing bee."

And Coven Mate Jen from Wheel of My Year wrote,

"I discovered Missing Witches through Queen of All Queens, Jinx Monsoon's podcast.

After reading their contributor covenant, I thought I would give it a chance and attended a new moon circle. As a queer person of color living in a flyover state, I had very low standards. I was used to being burned by performative allyship and virtue signalers.

These witches were different. My first circle was a transformative experience as a solitary witch. Missing Witches Coven is what was missing from my practice. I'm so grateful to be found."

Anyway, those are some of the people who bring you this podcast. And if that sounds like your people, then come find out more at missingwitches.com. We've been missing you.

[00:01:33] Risa: I'm going to take a deep breath.

Welcome listeners. Welcome. Witches, spirits, friends, lovers, whoever you're channeling today, great bright swaths of color from the future. Thank you for joining us at the Missing Witches podcast and thank you especially to my guest today. I feel so fluttery and like I have a celebrity crush on this Academic writer, which tells you both a lot about me and a lot about her incredible work. Julia Voss is here today. She's the author of THE biography. This is like the one you need if you've seen Hilma af Klint's work. And you felt this movement of her and this story about collective creation, these women around her, this story that's slowly unfolding, rewriting abstract expressionist history, teaching us new ways of writing a history of seeing, like, that's Hilma and the women around her and the person who took the time to go back and read.

All the journals, all the letters, translate her friends letters, translate other collaborators, situate us in time, is Julia Voss. And she's here! She said yes!

[00:02:55] Julia: Welcome! Thank you so much. It's my absolute

honor to be here, and I'm very, very happy. And thank you so much for this very kind introduction.

[00:03:03] Risa: That's my pleasure.

I actually read the graphic novel that your husband illustrated and and then read your afterward and then understood, there's layers of collaborations here. I wondered. Would you start off by maybe just talking about how you think about Hilma in the context of collaboration and, and how that collaboration has been for you?

[00:03:28] Julia: Oh, that's, that's a good take on starting also, yeah. So, I mean, it's crystal clear that Hilma af Klint's work is a collaborative work on many levels. So there's the the collective of the ghosts and spirits she works with, there's the collective of the women she works with, or, or maybe we should sort of say the collectives because it's several collectives of women she works with.

And then also working on Hilma af Klint and has been a collective journey, I must say. So the first person who actually introduced me to her work is Iris Müller Westermann, who is an art historian who was back then working in Stockholm at the Moderna museet, and she took me around in the museum and we went together in one room and there I saw the first Hilma af Klint painting in my life, which was in 2008, and then Iris told me everything she knew about it.

So that was The introduction and that was the start. And then I said to Iris back then I was working at a newspaper and I said, Why don't you keep me updated on everything you do on her and I can report about it in the newspaper. So that was sort of the first collaboration on Hilma af Klint.

And I think working on Hilma af Klint makes you meet a lot of other people who are also absolutely in love with her work and with her as a person. So a very important person has also been Halina Dyrschka, who has done the Hilma af Klint documentary, which is beautiful. And now I'm working together with Daniel birnbaum on a exhibition actually of Hilma af Klint work and Kandinsky's work, which is going to be shown next year in Germany.

Yes, and I did a collaboration with my own husband, Philipp Deines, which came very naturally because once I decided I would write this biography. I spent a lot of time with the research. And there were also journeys we did together. So one journey was to Italy, because I wanted to find out whether Hilma af Klint really was in Italy or whether she just kept, you know, a book with drawings that would show kind of famous places and famous Towns in Italy.

And so we tried together, my husband and I, to track down the places she had in this notebook, and because he can draw himself, he was very helpful in finding these places because we could, once we would go into a hotel and try to check on which level she did a drawing of a church in Florence, and he would say, oh no, it's not this window, it's another window, and we would look and For all the windows, and then we would actually find the very window from which she drew this church.

And so that was the beginning and then, you know, we talked about it a lot, and then we tried to imagine scenes, and I said, you know, it's in a way, it's, it's a pity there's so little photos of hers. There's so many things she did, you would like to see, like, you know, her traveling in Italy, for example.

And so. It came quite naturally that he started doing drawings on her life and finally it, yeah, it developed into an entire graphic novel called The Five Lives of Hilma af Klint.

[00:06:55] Risa: I love the graphic novel in a different way than I love the biography, specifically because that, because I can see things, you know, I want to, I want to picture what, I don't know what she was like, he takes maybe, I don't know if it's liberties, you'll be the one to tell me, but like we see her holding hands with Anna in Italy, we see them in love, and from what I understand in the biography, there's really only like tiny clues that they were there together,

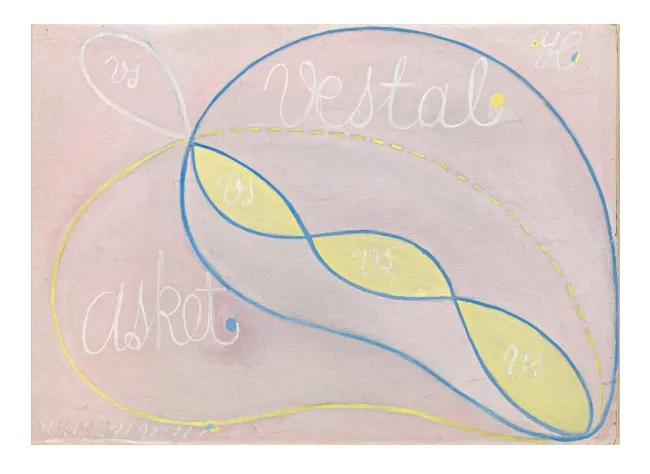

[00:07:21] Julia: Yeah, there is a note that which says that they travel together. that's clear. And the nature of their relationship is not that clear. We know it has been very intense and they will work very closely together. And, but there's, you know, there's no note that says they had a physical relationship and somehow they, they have these names for each other, which is Vestal for Anna and Ascet for Hilma and the Vestal is the priestess in the temple that guards the temple and that's Anna and the Ascet is named after being living as, how do you say that, ascetic in English?

Ascetic.

Ascetic. So, in a way, the, the very fact that they have chosen these names makes me think that they had a very strong platonic love rather than a physical love.

But who knows?

[00:08:20] Risa: Yeah, well, it seems to like they, there were, there, it seems like maybe they struggled with it. Like, they were halves of the same entry point, the same archway into some way of understanding. But, maybe it was too far.

[00:08:38] Julia: Yeah, I mean, that's, that's also something you can find in the notebooks.

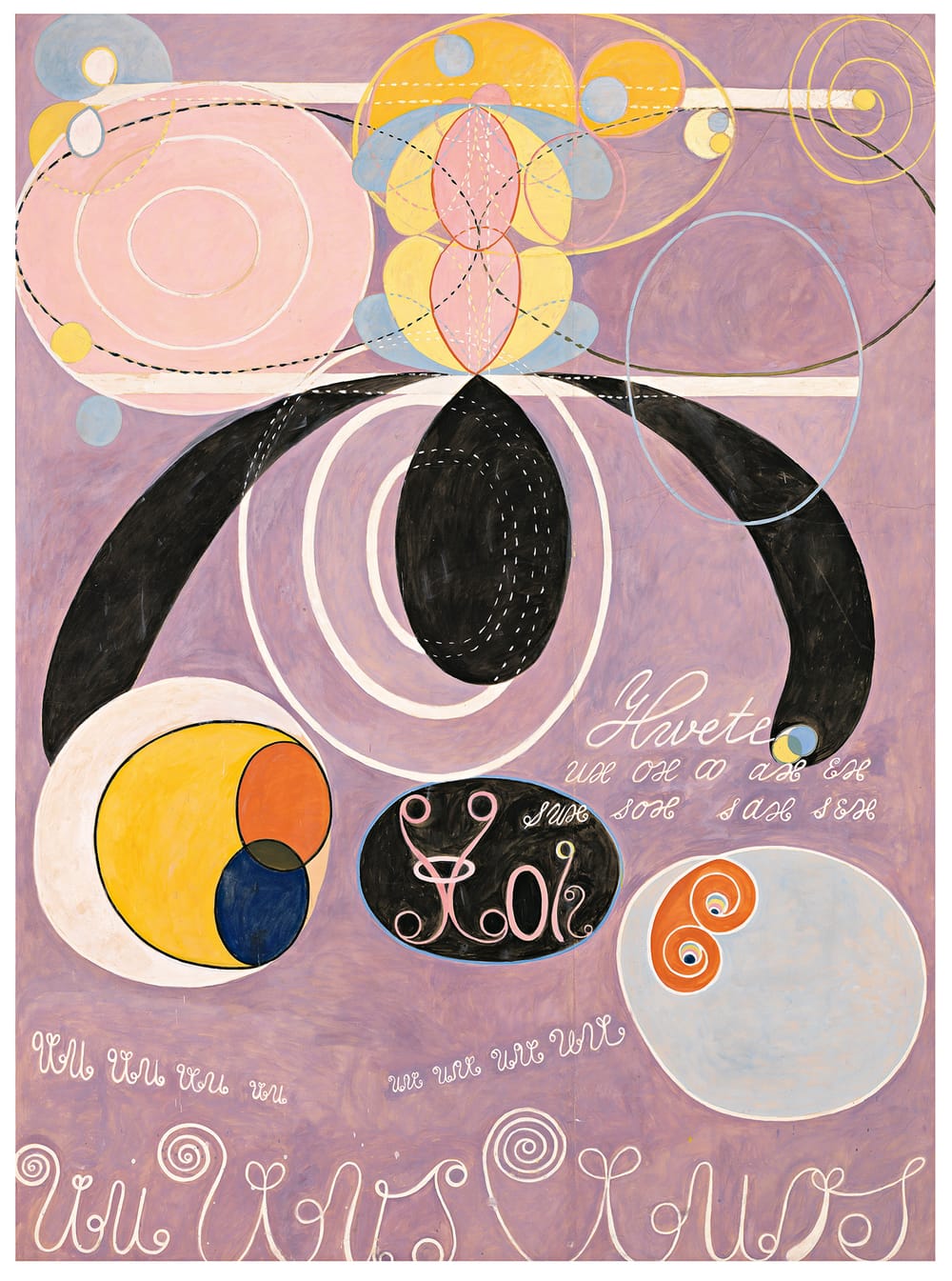

I mean, there's a lot of sexual energy, I think, in the paintings, you can see that. And there are also things that look like sexual symbols. I mean, there are things that look like ovaries sperms.

And also how things move in these paintings, they often sort of melt with each other or inseminate each other. So you have the feeling that it's a lot of being of connecting with other entities in all kinds of different ways and sex is one way of connecting with other entities. So, and also in the notebooks, there is a lot of kind of coded talking about sexual,

And I think because there's one notebook, which is not by Hilma af Klint, but by one of her female friends who actually also lives with her for a while in the same apartment. And this person called Siegried Lansen, she describes Hilma and her kissing and hugging and sharing a bed.

So, you know, maybe because we have this record of Something actual happening that I tend to be more cautious with the other women.

[00:09:51] Risa: Yeah. Well, and I think that's fair, right?

Like we don't have to paint her entire life with one brush to say there was relationships of this kind and she found her seems like she found her life partner by the end, but there were times in her life where that wasn't what it was and maybe that didn't feel like safe to be that way at that time.

[00:10:13] Julia: Yeah, yeah, yeah,

There wasn't, I mean, they don't even really use,

A word for it. So they wouldn't, you know, they wouldn't talk about homosexuality or they wouldn't, you know, refer to themselves as lesbians or same sex relationship. All these words didn't exist.

I mean, I guess that existed somewhere, but they didn't use them. So for example, one of the coded descriptions is that they talk about Spartan. Do you say Spartan love? Yeah. And that is. Because there are sources that reported that that the Spartans, you call them Spartans?

Yeah. Yeah.

That Spartan women had sexual relations with other women, like in antiquity, a lot of Greek men had sexual relations with other men. Some authors believe that this was also true for Spartan women. And so they talk about Spartan love. And I think this is like a code word or a way of, for themselves to get sort of an idea about the way they want to live. Yeah. And also to find maybe, historic forerunners for what, what they are doing.

I think for women, it might have been a bit. easier to share that kind of love because women living together was nothing people, you know, cared about and I think probably a lot of people would have been less suspicious of women sharing a life than they were of men. But still I guess,

Yeah, it's, it's something they had to develop themselves and see how, how they wanted to practice what and, you know, since there were a lot of women I guess, or, you know, each of them had a different idea of what should be done and could be done and could not be done.

[00:11:57] Risa: How do you think the channeling practices, the medium practices, all of those aspects of the rituals that they participated in and in some senses created, how do you think those spaces served for them as a way of like talking through things like that, talking through ideas, or how do you think that happens in general?

Have you participated in a channeling session? What do you think happens? Do you think there's an aspect where This was a way of liberating some ways of talking about things, it's coming out in automatic writing and so I can detach from what I'm allowed to know, and sort of open up questions.

[00:12:43] Julia: Yeah, yeah, I guess, I guess this is what happened that in a way you, I mean, much later the surrealist movement used the kind of same techniques in order to release, feelings they had and, and desires they had. And I think the automatic drawings also are full of desire and also the text.

I think the text also developed when you look at the first collective, the five, it's much less, Sort of sexual than later, I think, especially from 1905, six onwards, and the language is much more energetic and then many more sexual symbols in it.

And something new develops and you also can see that on the canvases I mean they're also a man and woman shown having sex actually on one canvas so it's pretty explicit. And, yeah, I believe these rituals were there in order to release that. Unfortunately, I sort of, for my taste, the rituals are pretty... you know, if you look at what happened, I tend to think that something extraordinary must have been there before, you know, but it's not like they do anything that's It's more than holding hands and praying.

They do quite normal things to unleash and to release this ecstasy that comes. So then, you know, there's some magic that happens that is not quite explicable by the rituals they're performing.

[00:14:27] Risa: Say more about that. What do you, where do you think that magic is or what, what is it? The magic that was there before.

What does that mean? Or just unpack more of what you're thinking about?

[00:14:38] Julia: Yeah, I mean

Yeah, that takes us right to the center. I mean, you know, I've been trained as an art historian. And so in the beginning, I was pretty much I wasn't really at ease with all the, with all of this, you know, I, I thought, you know, this, in the beginning, I thought maybe people have overdone it because, you know, often that's, that's a kind of stereotype that's.

I don't know, a woman is kind of turned into this crazy weird witch that does this, these paintings because we don't have any better explanation for that. But then I learned Swedish and also started reading the notebooks and it's all over, you know, nobody has overdone it. It's just on every page.

And I don't have any good explanation for that. And I also cannot really categorize it, but I, really enjoy the beauty of it. So it took me a while in order to find a good example that would help me to write about it. And in the end, I think the literature that helped me most was not art history, but it was like real literature.

Like you know, I reread Isabella Allende her is it House of Ghosts? In English.

House of Spirits?

House of Spirits, maybe. Yeah. And it really helped me just to stick to the phenomenology because in magic realism, all these things happen at the same time and you don't. You know, you're not forced to explain it.

It's just there. And I, this is in the end how I decided to treat the notebooks. I'm not there in order to sort of explain who these spirits are and where they come from or whether we should sort of explain them away by saying, I don't know, you know, that, that it was their

way Being able to do what they wanted to do. I don't, you know, I don't want to put any psychology in there and I don't want to put any sociology in there.

It's, it's what it is. I mean, she left these notebooks and I don't have a better explanation. Hilma af Klint herself wondered her entire life what she was in touch with. She tried to explore it in many ways.

And she didn't have a clear cut answer. I mean, I think towards the end of her life, the spirits she talks to, they tend to refer to her as a mystic. So, I guess she accepted that. But it's not like she has a simple theory of what was happening to her. And I don't have one. But it's beautiful. I think that's the most important thing.

[00:17:15] Risa: I do love the way it's treated in your book. I felt like, on the one hand I really appreciate your sort of refusing to dismiss her spirituality, her mediumship, but also like, let's ground, she was an artist. She was a professional, very well trained. Working artist, working artist for money. She tried to exhibit her work repeatedly.

She understood what she had made. What she painted, she didn't do in some sort of, maybe I'm wrong about this. It doesn't seem like it was like a fugue state that we could say, Oh, she wasn't even the author. She was overcome. Like she's clearly a. Technically incredibly proficient and making choices, but both sides are real.

She also is painting a commission from the spirit world. Yeah.

[00:18:08] Julia: What was important for me to see is that, that it's a dialogue between her and the spirit world, because in the beginning I was also off put by the idea that it's commissioned because I thought, you know, here we have a brave woman who does all these beautiful paintings. And then it's just a commission by someone else by some sort of higher beings. Right. And, but the more I read, the more I understood, for example, the spirits asked her, would you like to do that? And then she answers, yes.

And then, you know, when she has moments where where she's unhappy, they, they support her and they try to cheer her up or they applaud her on her paintings.

So they're also like invisible friends to her. And, and it's good to see that it's not a, not a hierarchical relationship where someone sort of commissions something and then she executes it. And then, you know, something new is being commissioned, but it's a dialogue.

And Yeah,

This was for me a relief to see and I think you're also right, it's the mixture, and she also talks about this later on in the 30s, she gives a lecture at the Anthroposophical Society in Sweden, and she talks about the relationship of being given something and developing something, and that she feels like both ways are justified, and she has experienced both, she has experienced being given something, but she also has experienced developing something, and I think it both comes together.

I mean, particularly if you look at the, at these giant canvases, that's nothing you can do you know, if you're not fully on the project you're working on it's nothing you can do sort of with closed eyes and not being

Right, I mean,

[00:20:00] Risa: she's physically making the paint. She's stretching massive canvases. She's working from symbols that she's developed over decades. She's an active participant.

Julia: Yeah. And she also tries to talk her, I mean, her real friends, her female friends to help her. So there is a collaboration between her and Anna, anna Kassel on the first series called Primordial Chaos. And then, but also the It seems to be like there has been tensions and this is also being talked about in the notebooks that sort of, it says that Anna should decide whether she wants to paint or whether she doesn't and then Anna drops out and then later on it's Cornelia who helps her with the large canvases of the ten largest. And then Cornelia drops out. And so, yeah, I mean, there are a lot of choices and there is a lot of work and there are a lot of, practical things that need to be done in order to make these paintings.

So, yeah, I guess it's both. It's something she received and something she developed herself.

Risa: What do you think about the idea in the Saga of the Rose book and the essays in there that Anna's paintings are like the prayer book to go alongside the imagined temple that like these two things are halves and that they should somehow they belong together.

Julia: I mean, this is also something that comes up in the notebooks. In the notebooks, there are several passages where both works are treated. Hilma af Klint's work and Anna Cassell's work and they are treated as separate entities that could potentially both be part of the temple.

And in one passage I think of now is, it says that Hilma af Klint's paintings would be the paintings of the future, Whereas Anna's paintings would be the paintings of the past of the Akasha Chronicle.

So, yeah, I think they're believed to be two parts of one thing. Although, So far we have only studied Hilma af Klint notebooks, and it's clear that also in terms of dimensions and in terms of size that Hema Aftin paintings are the dominant ones. There are also passages where they talk about how much space these works should take up, for example, in the shared, studio house they built on Munsu. And it's said that Hilma af Klint should receive, like, three quarters of it and Anna should receive one quarter of it. So I guess they, yeah, they are twins. But they are kind of uneven twins, let's say.

Risa: Yeah.

Something about the size, too. Those paintings are different in scale. Yeah.

[00:22:54] Julia: And it also seems, I mean, Hema of Klint has exhibited her work during lifetime.

There's one exhibition we know of in 1913. And there is one exhibition also in London later in the late 20s. It's her paintings of the temple that she shows in London. So I guess there was, among them, there was a kind of tension what exactly the relation was between these paintings, between these works.

[00:23:23] Risa: What do you think the ideal future home for these works is it seems like there's debate among members of the foundation or there's legal things I can't really follow all of it, but what would your dream version of it be.

[00:23:42] Julia: That's a very good question, because I mean, what I really like about Hilma af Klint's idea of the temple is that it's something it's on the one hand, something outward, a building, but on the other hand, it's also something inward. It's something you built in yourself and she built in herself and the women around her built in themselves. So it's a work that needs to be done inwardly and outwardly. And on the one hand, the situation now is quite beautiful that these works travel all over the world and people get to see them in Europe, in Australia, in North America 2025 they go to Asia also. So this is beautiful. But this is also something that's not very sustainable for the paintings, because you know, traveling is not good for paintings, because it damages them. I, I wonder it's also I mean, it's clear we want to have a place that could be visited by a lot of people and since Hilma af Klint thought of her paintings as something that

that should stay together, probably a building in, in Sweden would be, would be the place to be, but I'm, I'm cautious, I think, yeah, I don't know, I, I, but also,

maybe, sorry

[00:25:10] Risa:

It seems like it's a, it's a emotional question somehow, right? Where do these live? How do we, yeah,

how do we honor them?

Where do they go?

[00:25:19] Julia: Yeah, no, that's a very good way of putting it. It's a very emotional question. And since there are so many debates already, I, you know, I'd rather talk with a lot of people and see what can be developed rather than say, Oh, you know, this is. This is the right place or this should be done.

I think a lot of people should be involved and then there should be a broad discussion of what should be done.

And I also like the ideas of what's happening right now that there are loans to several museums. I mean, this is usually in, in art history, this is usually how an oeuvre is being spread right you have a lot of museums that show works by these artists, and that's The best way of making sure that a big audience can see them.

And so just putting everything in one place, in one building could also feel a bit claustrophobic. I don't know, maybe it's beautiful, maybe it's a temple and it's beautiful, but maybe it would also mean that a lot of people can never see them because it's just too far away and too difficult to reach.

I also wonder, maybe this is heretic, but I also wonder, I mean, she didn't sign her paintings, right and she, we also know that there's one series she copied, So we have two versions of it, the Tree of Knowledge series exists with the Hilma af Klint Foundation And then there's an almost identical copy that was done by herself, which has been sold to the Glenstone Museum and was shown in the David Zwirner Galleries in New York and London.

And, you know, in the Middle Ages, this would have been the way to spread a work is you copy it, you multiply it, and then take it to a lot of different places, libraries.

And I sometimes wonder whether this could also be a way. Maybe there should be several several versions.

[00:27:23] Risa: Yeah, I like that too. Although if it were me, I would insist upon the beginning, you know, with ritual and

yeah! inviting those collaborators...

[00:27:34] Julia: No, absolutely. I mean, it shouldn't be copied in a casual way. You know, you would have these sacred books of the Middle Ages. Take, for example, Hildegard of Bingen's visionary works they were illustrated and copied and multiplied at several places. And that was the way to spread them.

[00:27:52] Risa: I love that idea. As soon as you said this might be heretical, I was on board. Can you talk about like, so she's, she's studying, She's interested in Blavatsky. And then she kind of leaves it behind with Steiner when he makes his break. And, and she says repeatedly, you know, that she's working with Steiner and this is anthroposophist work . But it also seems like she's going her own place. Does that, does that sound right to you? Like what, you know? Does she exist just in one of these traditions? Is she just trying to illuminate his thoughts or is there something more that she's saying on her own or, or channeling on her own?

[00:28:34] Julia: Oh, I would very much see it that, that she's, you know, there's a lot she's saying on her own. And that's also how Steiner saw it, I think. He didn't see her work as something that would perfectly illustrate what he was doing. I think the relation to Steiner is a difficult and troubled one. For a lot of people Steiner completed, what a lot of people tried to do.

So, I mean, Steiner built this beautiful anthroposophical Center in Switzerland started in 1914 and then was finished and then Hilma af Klint also went there actually nine times in the 1920s. And so Steiner was the one who was really able to construct this entire universe which had, you know, a building which burned down, but he rebuilt it. A building text. art. He collaborated with a lot of artists. And maybe I sometimes wonder whether this was also something that's attracted Hilma af Klint a lot because he completed what he wanted to do. And, and it's absolutely clear that he comes up in all her writings.

She cites him a lot. She has, you know, almost every of his books.

She gets a lot of ideas from Steiner and she inspired a lot by his writings.

And you can see that also, I mean, for example, if you take the series Tree of Knowledge there is a text by Steiner which is very close to what she's actually drawing, it's a tree that is turned upside down, it's a kind of travel that you do inside your body and outside in the universe and Steiner talks about it.

And it's, I think when you read this text and you look at the paintings, you feel there's a very closeness and there's a lot of fondness in her paintings of his thinking. So while he was still alive, she. She didn't manage to get his full attention. I mean, it looks like they met around 1910, probably and that he actually saw her paintings and commented on them, but he wasn't taken by them. It's not like he thought, oh wow, you know, this is excellent, and I would like to have them in the Goetheanum, and we should work together. He doesn't discourage her. He doesn't say like, I mean, that's, that's a myth, that developed later. He doesn't say like, you know, stop and burn it and don't think about it again, but he also doesn't encourage her to bring everything to Dornach and, you know, have it there.

So she tries over and over again to press him to get kind of a definitive answer on what he thinks of her paintings and he dies before Hilma af Klint gets it. And then something interesting happens so later in her notebooks, Steiner comes up a lot and they actually talk to each other.

So it's Hilma af Klint, the living Hilma af Klint, talking to the dead Steiner. And suddenly they are one. How do you say it? One heart and one soul. Yeah. Yeah. So, and he even gives her advice on how to color something and how to proceed and so forth. So from her perspective later on, they had a very good relationship and it was very close.

they even found a spiritual university together.

So something, yeah got better. Yeah,

[00:31:59] Risa: yeah, I, I love how you, you sort of unpack that because there is this sort of like you, you Google Hilma of Klint, you're going to get stories about how Steiner told her that the world wouldn't be ready for her work for 50 years.

And then Julia Voss goes through all the notebooks and is like, never happened.

[00:32:18] Julia: Yeah, I can see how the myth developed because it's like, you know, a line in one book and then, you know, it's taken a bit further in the next book. And there was, I mean, there was a degree of disappointment in Hilma af Klint, that's clear. She would have, you know, she would have liked if she got his full support and she didn't get that.

So there is a little bit of truth in it.

And the other thing is that Steiner was really skeptical of visionaries. This kind of working sort of unconsciously and completely receiving something wasn't something he was fond of. And I sometimes wonder, this is just speculating, but I sometimes wonder Steiner was in Weimar before he joined the Theosophical Society. And in Weimar, he experienced also Nietzsche who, Was then in a state of almost unconsciousness and had all kinds of outbreaks and he was the first biographer of Nietzsche's actually, and I sometimes wonder whether he associated with being, you know, in these hallucinatory states, whether this reminded him of Nietzsche, which was a very sort of off putting example of someone sort of losing his consciousness.

And maybe that was an experience that he digested by staying away from that.

And in a way, you know, it took, it took me a while to understand that these kind of visionary states or ecstatic stage states Hilma af Klint was in, were actually something very enriching and beautiful for her. Because we have a lot of cases of people who, who work kind of in a visionary state or in a ecstatic state and have these breakdowns afterwards. And that's, you know, that's also something very scary. And I think the difference with him after is that, that she managed so well, with reaching out to the other side.

[00:34:17] Risa: Yeah. And there's, there's bits you quote that sort of indicate that she, she changed in how she saw her relationship with the messages she was receiving, that she had to become more of like a chooser, she had to become more of a interlocutor or something with the messages coming through, that the nature of her relationship with that world changed, maybe in a way that, that Steiner wanted her to reach for or something.

[00:34:47] Julia: I think, I mean, it's inevitable if you experience, make these experiences a lot, you develop a way of dealing with it. And I think this is something that's that also happened to her that, you know, from probably being very overwhelming in the beginning that it became more manageable the longer she did it.

And also, I think she, she tried different channels. So from when World War One rages at almost at the end of it, she develops this very pantheistic attitude towards what's around her. So I think in the beginning you would always have these flowers in her paintings and you would have all kind of organic forms, but then she turns to actual flowers in her environment and tries to channel their souls and succeeds.

This might've been another door to entering different, another consciousness. You know, through a kind of pantheistic melting with the world that's around you.

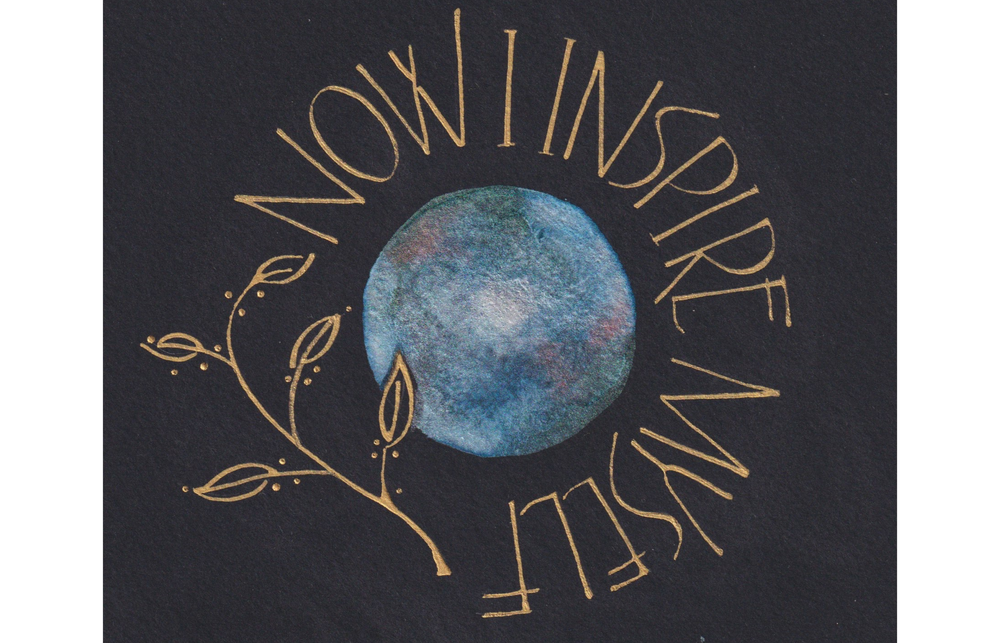

[00:36:01] Risa: What do you think, you know, we talk about paintings for the future. She was writing for us somehow or painting for us.

She was throwing images forward. I interviewed an academic who writes about Witchcraft and channeling and she said when she saw the Hilma show at the Guggenheim she felt so emotional feeling like this woman had succeeded in tossing these seeds you know that they were for us they she threw them far enough that we we caught them.

Yeah

What do you feel, I guess it's not so much a question of what do you feel she was trying to toss us because I think sometimes she wasn't clear what the messages were, but what do you feel like when you've looked at all these paintings and read all these notebooks, what are you left with wanting to underline or, or, or, or yell loud on her behalf?

[00:36:57] Julia: Oh she wouldn't want me to yell.

Just very politely.

Yeah. I mean, what, what I find really touching and really, and I mean, you're right. It really feels like a gift. And I think this is why people are so moved when they see it, because they feel like something really, something generous is offered to them.

And it's not rigid in the sense like it says you know, this is the system you believe then actually it's all wrong.

Here's the new system. Take it.

It's more like, it's very tentative, right? I mean, it's more like why don't you try to connect with something else and reach out and put your feelers out in order to build a bridge and then let something new come in and develop. And I think this is the idea that you never, you, you know, you never stop.

If you are open for the things around you and if you try to connect with them, then what you receive is that it's, it's a lifelong evolution and maybe even longer. If there is a message, that's the message that it's a message of, of the gift of lifelong evolution and even beyond that.

[00:38:17] Risa: I love that you said why don't you put your feelers out as one of the messages from her? Can you talk more about how we see that in the paintings?

[00:38:27] Julia: So there are actually, I mean, in the 10 largest, you have these, it's also primordial chaos. One organism that comes up again and again is the snail, right? And the snail with feelers and they are also in one of the 10 largest you see two snails sort of touching each other with the feelers. So I think this is why the metaphor of the feelers also came up for me. But it also, it comes again and again in different forms. So sometimes you see two things that, go into each other, and then, you know, a blue circle meets an orange circle, and they make green together. And also in a series like Parsifal, it's almost like two planets and then one planet sends out something that, you know, it could be a seed, or it could be, it could be even a spaceship, and then it flies to the other planet, and then the other planet gets illuminated, and then it returns something that goes back again.

So this reaching out and trying via moving and whirling to get to something else, I think it's almost in every painting.

[00:39:34] Risa: Yeah, me too. So you come to these paintings with so much more than I do you're an Art Historian. And you had that moment where you saw the first one, and then you went and you saw more, and you saw them in a context of art history.

What stood out? Like, why were they important? Why were they beautiful? What, what did you know about them when you saw them and you knew the context of art history? Do you know what I mean?

[00:40:02] Julia: Yeah, yeah. So the first time I saw them in 2008 when I was in Stockholm, they were presented, I think they were surrounded by Russian constructivist works.

And I felt color wise because they, It was a painting from the Swan,

There are two that are very geometrical, one is red, one is black and they have these circles in the middle they are sort of cut in half. And I thought, wow, you know, color wise, this white, red, and black really looks like Russian constructivism, but on the other hand, it also looks more organic.

It's less Rigid and it looks strange. And maybe when I saw them, I thought maybe they were done a little bit later. And I think a lot of paintings look like they could have been done much later. And then, as I said, it was when Iris Müller Westermann started telling me about what she knew about it.

But yeah, I mean, in terms of art history, the story we have been told over and over again is basically that Western art abstraction was invented by these men starting from 1911 starting with Kandinsky and then Mondrian and Malevich, and that they sort of turned this into a style and then more and more people joined in and I think that's one of the reasons why it took so long to rediscover Hilma af Klint, because she completely crushes everything of that story of art history. Suddenly it's a woman, suddenly it's earlier, suddenly she's not in Paris, moscow, or Berlin, or Munich, but she's in Sweden. Suddenly that we have spirituality written back into the story. I mean, that's something actually that was very important also from Kandinsky, but I think it was written out of his story. Later on when his works became famous. A lot of people thought, you know, that's too strange. Let's not talk about it.

And so,

yeah, she seemed to be kind of this odd person who would challenge art history to either rewrite everything they believed in or leave her outside. And this is what what happened for a long time. But now she's back in, for sure.

[00:42:19] Risa: Now she's in. Yeah. Oh, now she's big news. She's, Pharrell made NFTs of her work.

I mean, there's so many, there's so many people trying to bring her work into different spaces, capitalize on it, or make it accessible.

[00:42:37] Julia: Yeah, I mean capitalizing on it is difficult because they all belong to one foundation. And they... They're not selling. Every now and then something comes up on the market.

These are works that have been given away by her during lifetime, and they were sold. So the tree of the second version of the Tree of Knowledge was sold to David Swirner. And then the Museum of Modern Art actually has acquired a big series from the 1920s.

But looking at the complete body of work, the big works all belong to the foundation and it doesn't look like they are selling. So this is also outstanding. I mean, usually people enter the stage of art history or come back on the stage of art history. There's also a market that fuels that rediscovery and makes these works circulate.

And in Hilma af Klint case, that's... That's not what, has brought her back. And I think this is also very extraordinary.

[00:43:39] Risa: Is there anything you feel like people aren't talking about enough about her work?

When you read articles or books about it, you're like, spend more time on this piece or someone investigate this.

[00:43:52] Julia: Oh gosh, I mean, there's so many things that could be talked about and I'm sure people keep on discovering things in our works that we have overlooked before.

And actually right now working on Hilma af Klint and Kandinsky on the show that will be shown next year in Düsseldorf in Germany. And discovering so many new things in her paintings because, you know, you actually look at them for a longer time and then you realize, oh, gosh, you know, this is an illusion to that and so forth.

So, I mean, this is one thing I'm spending a lot of time on now is looking at the paintings and trying to figure out what, what inspires her beyond the spirit world. Because sometimes theyre are also allusions to iconic traditions that are also there. As you said, she's a trained artist. She's sort of, she knows art history and she has traveled. She has looked at a lot of things. She has, notebooks with drawings of other paintings. She looks at Rembrandt. She looks at folk art. She looks at a lot of things probably also from her time that she doesn't bother to take down on her notebooks, but that were there. So that's something I'm interesting in,

but this is maybe a bit sort of. Art historical jigsaw playing.

What I really liked when I saw the exhibition on Mondrian and Hilma af Klint is that they stressed so strongly her kind of ecological view. of the world. And I think particularly when she starts in 1917 when she gets more and more pantheistic and connects with flowers and connects with,

Small organisms around her that gets very strong in her work. And I think this is something that would also help us to get , or me, I mean, there are people who already have a better relationship to the world around them. But I think in order to get a different idea of nature, rather than just looking at nature as a resource, but actually respecting nature as something that is a being in its own and has a life and has individuals and organisms we should connect with. I find her work really helpful for building a bridge. And I think this will make us think a lot more and we will come back to this.

[00:46:13] Risa: Yeah. I think so too. There's been so much brilliant work mostly by you putting her in To a rewriting of abstract expressionism, but you think there's another lineage that she Belongs in, like, there's Mystics, Revelatory Women, Monica's Sjöö, Hildegard of Bingen.

Is there a different story there still to be told? What are we learning from these women who tried so hard to tell something that they couldn't tell in their present, it feels like?

[00:46:44] Julia: Yeah, I mean, this, yeah, I mean, certainly there's a tradition of visionary women. She also, I think, at least explored whether she put herself, she should put herself into that.

So there is a notebook where she looks back at visionaries and also touches upon Hildegard of Bingen. And Hildegard of Bingen is someone actually, I think I discovered through Hilmar of Klint, because I mean, I knew the name before, but then I saw in the notebook and then, you know, Bingen is in Germany. I went there and looked at things and so forth.

So yeah, that's I think the beauty of it is really that there are a lot of things that cannot, that we cannot really explain. I mean, with Hildegard von Bingen, we also have people, even like Oliver Sacks, who is usually a brilliant author, and I, I like his writing a lot, but, you know, he had this idea that Hildegard von Bingen basically suffered from, Migraine.

But you know, a lot of people have headaches and migraines, but it's not like they come up with the same things. And if you look at her paintings, her visionary paintings, she didn't do them herself, but

the experts I trust say that she, how do you say that she commissioned

them, right?

She commissioned them and told the nuns who executed them how to do them.

And so if you look at these small paintings from the 12th century it's, it's really extraordinary because there are all kind of illusions to text and pictures from that time, but nevertheless, they also look like nothing that was being done at the same time.

And we have to come to grips with that. We have to accept it in a way. Whatever it is, whatever that kind of state is, and wherever it comes from. It's a kind of state that was able to produce something that we don't have any better explanation for.

And. I love that. It reintroduces the kind of wonder into history.

And I think you know, we, we should be modest and accept that.

Yeah. Unless we come up with a better explanation, but so far.. . I'm reading the book by Margot Fassler, who is a professor in North America.

And she has a way of. Explaining everything in these paintings. It's beautiful. I mean, she can, you know, open them like a nut and then sort of say this is this and this is that and explain everything. But you know, at the same time, although she can make these pictures talk it's still a mystery where they come from, where these forms come from, and how they ended up in Bingen.

Right.

[00:49:22] Risa: Right. And it sometimes feels to me like they belong more in a continuous history with Indigenous abstract work that expresses spiritual worlds, you know, that there's, there's this real long 10 000, 30 000 year history of people making...

[00:49:39] Julia: yeah, you're absolutely right. Unfortunately, I know very little about it, but I remember when the Hilma af Klint work were traveling to Australia and New Zealand, I thought, you know, Gosh how do they connect with the abstract traditions they have there from the indigenous people who have done these beautiful abstract paintings for a long, long time, there are loads of them are much older than anything we can imagine.

So you're right. I mean, this is also something I would love to read. I can't write it, but I would love to read it.

[00:50:10] Risa: Me too! Listeners, you have two of us first in line when you write this missing book we need.

[00:50:18] Julia: Please.

Hey,

hello. Were you listening all the time?

[00:50:24] Brienne: Yes, and I'm very starstruck. Your book is incredible. Do you have time for just a quick question? do you think Hilma, when she created Art for the Future, do you think she was at peace with that?

Or do you think she really struggled to surrender to it?

[00:50:40] Julia: I I I, I'm trying

to see whether I get you right so that it's not for the contemporaries, but for the future, whether this is something that she also found slightly disappointing.

[00:50:50] Brienne: Yes. Yeah. Okay. Actually,

[00:50:53] Julia: yes, I believe she struggled with that. So I'm, I mean, we can see that she was, busy trying to exhibit her work until the late 20s.

And you know, and it didn't go well. And it must have been a disappointment for her. You know, if you are willing, for example, to ship all your works to London and, you know, speak at an exhibition, even though you don't know English, and, you know, you make all the travel, and you pay

for it even yourself and everything then not

getting, I don't know, a lot of attention is something that must have been very disappointing.

Right. And also the fact, you know, that Steiner was nice and polite, but not, you know, out of his mind when he saw her works is also something that she, I thought, found difficult.

And, and also, I mean, she She was very inventive in the many ways she tried to reach an audience.

So, we see from 1919 onwards that she suddenly switches to German, which I think is also a contribution by Thomasine, because Thomasine can speak German.

And then hilmar Afton switches to German and produces these texts in German. And I think they were meant to be for a German audience. And she thought, you know, if I go to Dornach, if I go to Switzerland, if I go to the Goetheanum, which was built by Steiner, you know, And I can reach this audience that speaks German, maybe suddenly everything is different and I find a lot of friends and it, you know, it didn't happen.

And then she made these called these blue albums, in which she did little reproductions of her work as photographs and as little watercolors, and they were also meant, you know, to allow her works to travel and we even know that they went to Amsterdam and they were sort of. Handed around in the audience of a talk at the Anthroposophical society, which was given by a friend of hilma's so she tried to open up all these channels, exhibitions, texts, albums, reproductions, and, and it took her nowhere during lifetime, or, you know, it, it wasn't a huge success, and I think that was a disappointment but, And then again, what's great with her is that she, that she didn't sort of turn it around and thought, okay, maybe the others are right. And I'm just, you know, a stupid fool doing these, I don't know, canvases nobody's interested in, let's forget about it. But instead she decides, okay, so that's the world I live in. I have to accept it, but I'm sure there are better times to come. I'll give that work to the future.

And then, again, a kind of rush of creativity came, and she had these ideas for how to build a temple, and where to build it, and so forth. So, I don't know. Again, she managed to, in a way, start over new. I mean, this is also something that really impresses me, the fact that she has the power and the the strength to start over and over again.

That is... That is something very cool. Remarkable. Remarkable. Thank

you. She must be working through you to get her artwork out to the rest of us in the world. So, thank you. Thank you. Thank you so

[00:54:12] Risa: much. The great collaboration continues. Thank you so much again, Julia. It's such a treat to meet you. Please also tell your husband how much I love his book.

I've shown it to everyone. I will,

[00:54:24] Julia: and he will be very happy about it.

[00:54:26] Risa: It's just so cool to see.

Yeah. Just to like get to feel her, like the paintings, the, the drawings where she's like floating in the world of the art.

[00:54:36] Julia: Yeah. I liked them a lot too. And I think this is also, I mean, this is. I mean, I guess it depends, but sometimes when I see her works in exhibitions and there are not too many people, it really feels like you can enter them.

And they are portals and they are doors and they open up a new world. And I love in the graphic novel that you get a feeling of that, that she is part of this world and that it's, it's a universe. It's not just something flat on a canvas, but it's a whole universe.

She opens up.

Oh,

[00:55:10] Risa: thank you so much is there anything you want to tell the listeners about how they can find you and support you and where do you want them to send their love and excitement?

[00:55:21] Julia: Oh, that's so sweet of you. So actually in these days the audiobook is coming out, of the biography and it has been read by Doria Bramante, and we will make a post soon.

So maybe I recommend that and I'm on Instagram. You found me on Instagram. And you know, any thoughts and love and considerations I'm more than welcome.

[00:55:45] Risa: Wonderful. We'll include the link to your Instagram and everything else we can find in the show notes as usual. And, bless if I can be

[00:55:54] Julia: great.

[YOU MUST BE A WITCH]

[00:55:59] Risa: The Missing Witches Podcast is created by Rea Dickens and Amy to rock with insight and support from the Covin. Amy and Rea are the co-authors of missing witches, reclaiming true histories of feminist magic, and of New Moon Magic 13 anti-capitalist tools for resistance and re-enchantment available now wherever you get your books or audio books. find out more at missingwitches.com.